THESE two selections set a framework—afford a comparative perspective—for all the readings that follow in this book by focusing on persistent themes in American urban imagery. An occasional reference back to this perspective should enrich the reading of later pages as well as add to the analysis elaborated here.

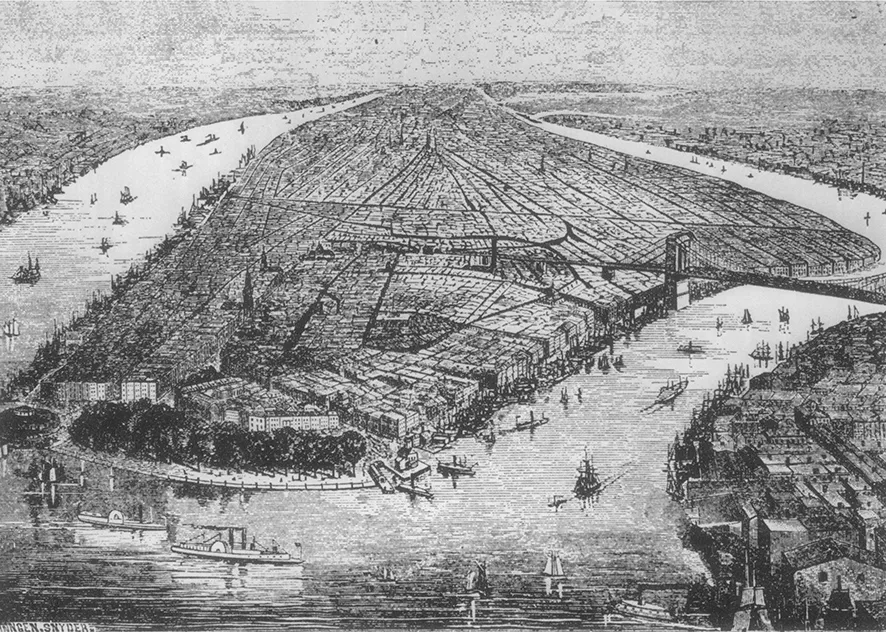

Urban Perspectives: New York City

Anselm L. Strauss

IN this essay (written in 1955 but hitherto unpublished), all the protagonists in the novels discussed live in New York City—a criterion for their selection. The urban imagery reflected in these novels suggests the considerable range of perspectives held toward a large metropolis like New York. These perspectives include the city as a place of diversity, as a place of fun and adventure, as a place contrasting with the countryside, as a dehumanizing environment, as a place conducive either to continuity or discontinuity of community and family, and as a place where complex relationships exist among the social classes

(mobility into and out of classes, conflict or cooperation among classes).

Looking back from his vantage point as devoted New Yorker—though by adoption rather than by birth—John Steinbeck has tried to recapture how he got that way.1 When, at 23; he first came to New York, “I saw the city, and it horrified me. There was something monstrous about it.” When he left, not many months later, the city had beaten him. The city was a place where one could be alone and afraid. Eleven years later he was back, a minor celebrity. Of himself then, he wrote: “Whereas on my first try New York was a dark, hulking, frustration, the second time it became the Temptation and I a whistle-stop St. Anthony. I reacted without originality: today I see people coming to success doing the same things I did, so I guess I didn’t invent it.”

Soon he plunged back to the rural West, convinced that the city was a trap and a snare. Some years later he finally did settle down in New York, although even then his country-boy distrust of the city would not be downed: “I was going to live in New York but I was going to avoid it. I planted a lawn in the tiny and soot-covered garden, bought huge pots and planted tomatoes, pollinating the blossoms with a water-color brush.” As he walked the streets for exercise, he gradually got to know them and the tradesmen on them, and eventually he felt part of the city, albeit his city had a village quality—without its “nosiness.” “My neighborhood is my village. I know all of the storekeepers and some of the neighbors. Sometimes I don’t go out from my village for weeks at a time.”

Each Steinbeck who came to the city was, in some sense, a different man; and each time he perceived, and therefore used, the city quite differently. “Perceived the city” is not quite an accurate term; “conceived” would be better. The urban milieu, or any milieu for that matter, is responded to not merely as physical terrain, a bit of geography, but as symbolic space filled with meaning and peopled with significant persons, artifacts, and institutions.

The newcomer to any city brings with him conceptions of urban life and perhaps of other cities, if not indeed specific notions about this particular city. Whether visiting or migrating to a metropolis of which he knows little beforehand, he must nevertheless learn to cope with it (however brief his stay) by obtaining or developing representations of what kind of a place it is, what can be done there, what the natives are like, and what kind of a visit or life he can have there. The native’s experience is not so very different. He has much more leisure to grow into his city, but he does not learn to visualize his city even geographically all at once; neither does he hold unchanging ideas about what kind of a place he lives in. Both he and his urban world change, and both invite re-representation. Steinbeck’s story merely speeds up and dramatizes a normally much more drawn out, and thus easily overlooked, process.

In the writings of novelists like Steinbeck, and especially in their works of fiction, the American city rarely appears as mere backdrop, as static stage setting, against which are enacted the sufferings and dreams of men. The city itself is perceived as animate and potent. It makes and breaks men: sometimes promising opportunities and providing for their fulfillment; but sometimes luring or trapping them, and exacting payment. American urban novels, whose characters move in and about a city landscape, provide a composite image of “the city” as conceived over the decades by an enormous number of Americans. This mass of urban folklore can help us construct a mosaic composed of some meanings that cities have had for Americans.

Taken as a group, novelists have portrayed life in the city not only more dramatically—more humanly, if you wish—than their scholarly contemporaries, the sociologists, the geographers, the planners; but they have been less heir perhaps to inherited intellectual views which divert gaze and cramp vision. One may instance here what is perhaps the outstanding single article by a sociologist on the nature of urban life, a paper by Louis Wirth 2 who, in the thirties, systematically set down what amounts to a range of urban perspectives measurably narrower than those expressed by the novels in any moderately sizable public library.

Having seen what the novelists have to say about social relations in the city, how their people imagine the city to be and how they cope with and use the city, we shall be in a better position to ask how Americans have come to see their cities in these several ways—and what difference it makes whether cities are conceived from one viewpoint or another.

Urban Heterogeneity

One classic theme of the urban novel pertains to the diversity of every large city’s worlds and populations. Drawn from the four quarters of the earth—or at least from neighboring states—the city teems with the people of different races, origins, cultures, and beliefs; not merely peoples of two or even three contrasting classes. This motif is reflected in the local press (boasts of the melting pot and living together, along with reports of ethnic and racial tensions); and in journalistic accounts which attempt to capture the color and spirit of particular cities, whose unique qualities are partly attributed to the characteristics of its diverse populations. Photographers of city life love to show its contrasts: the range of ethnic faces in the crowd, the multiplicity of kinds of city life, as well as the poignancy of Park Avenue and office buildings towering over slum dwellings.

The emphasis on heterogeneity enters into novels in much the same way. The city is a mosaic of worlds: it has many classes, ethnic communities, and neighborhoods. The city is a place, too, where diversity is attendant upon a vast division of labor. Novelists who portray urban occupational life sometimes combine the idea that an occupational world exists within a larger community with another idea that the city can be what it is only because key occupations (the newspaper, the police) function as they do.

Diversity is celebrated for it gives rise to cosmopolitanism. The very multiplicity of populations permits and fosters worldliness—for the city itself and for those of its citizens who “get around.” Some critics of suburban growth, ringing an inverse variant on this cosmopolitan theme, have feared that the very homogeneity of suburban populations will lead to conformity and lack of urban dash, color, knowledgability and sophistication. This criticism is beginning to get expression in suburban novels, such as the popular Tunnel of Love,3 where suburban living is pictured as dull and intellectually confining and city itself becomes the symbol of cosmopolitanism and vigor, lost to the suburbanite who finally capitulates to domestic and familial obligations.

The City as a Feast

Closely allied to the idea of cosmopolitanism is the complex imagery of the city as an exciting place. There are several components to this imagery that ought properly to be distinguished. First of all there is the city which is physically exciting and satisfying. The skyline, tall buildings, bridges, stores, city lights, dress and fashion, street scenes and sounds, urban dialects, the look and the smells of foods: all these and many more make up the characteristic urban picture. These sights and sounds are treated not as external to the perceiver, but as necessary to his very sense of identity, a contributor to and a necessary ingredient in the stream of personal memories.

Entwined with the physical city is the metropolis as a setting for exciting events. The stores, bars, brothels, restaurants, and places of entertainment all profit from the outsider who comes to the great center for a good time. “A big dirty city is better than a technicolor sunrise out in the sticks, no matter how many songbirds are tweeting. In the city you may feel lost, but you also figure you’re not missing anything.” 4E. B. White’s popular and poetic volume Here is New York, is largely written from the perspective of the stranger become a New Yorker (editor of The New Yorker, in fact) who has organized his life around urban excitement and cosmopolitanism: “you always feel that either by shifting your location ten blocks or by reducing your fortune by five dollars you can experience rejuvenation.” 5

A third variant of urban excitement is the city as a place of freedom. Contrast between rural and urban aspects of American life is usually explicit in this latter imagery. (“Meg came from a small town in southwestern Indiana, a place called Hinsdale, and as far as she was concerned it could disappear without a trace.” 6) The city is not only a place where people rise in the social scale, but find release from small town or rural conformity, and an opportunity to exploit and develop their native talents. The very anonymity complained about by some natives and visitors, is viewed as part of the requisite setting for freedom of action and, fully as important, thought.

In the novels, “excitement” and “opportunity” crisscross other urban themes. Domestic stability may be seen as inimical to taking full advantage of urban excitement; or class mobility is seen as linked with both opportunity and freedom, as in the discovery of the wider urban scene in the ethnic second generations; and despite the destructiveness of the city on family life, the city is seen as having a kind of hard asphalt beauty which the initiated can appreciate. Even the theme of community in the city, may be linked with urban excitement, as in the apochryphal joke told about the tenement woman who refused a vacation in the country with all its interesting sights, remarking that from her living room window she too could see some wonderful sights. To many people, city living spells civilization; even if civilization by no means signifies the same thing to all.

The Rural-Urban Contrast

To many others, the city seems a poor place compared with the small town and the countryside. Whatever the countryside has meant to rural and small town people themselves, to some city dwellers it has meant a natural environment and a natural way of living as opposed to what appears to be the hurly burly, tenseness, impersonality, and somewhat artificial character of an urban environment. The stereotype of rural life embodies notions of close kinship and friendship ties, of intimate and satisfying face to face relationships, of stability, simplicity, honesty, integrity, concern for associates, and other attributes of tightly knit groups.

In urban novels, these rural attributes enter in various ways; less rarely as major themes around which to spin a story than as elements in the story. Here are a few examples. In A Cathedral Singer,7 the city cathedral is pictured as the cornerstone of community and stability, and the symbol by which the present is linked with the past and the future. But the cathedral is also linked with the rural virtues of peace, safety, security, serenity, and love of one’s fellow man. In Louis Bromfield’s Mrs. Parkington,8 the virtues of city and countryside are combined in the person and education of one heroine. She derives from the healthy if crude soil of a Western community. Together with her ambitious husband, she invades the Eastern cities. At 84 she looks back, retracing the path by which they became wealthy and important. Her children are blue-bloods but without her own rural-based vigor. Yet the city has given to Mrs. Parkington that sector of her character which is cultivated and urbane. The important thing about her is that she has managed to become cosmopolitan while yet retaining a rural identity. “At the one end of her experience lay Leaping Rock, an utterly barbaric community, rooted in harsh reality; at the other . . . civilization. Both were good; the bad-half-civilized ground between them she had never trod, in all her existence.9 But a variant of rural-urban contrast that is probably more familiar to the sociologist is Ernest Poole’s treatment of the breakdown of family ties when a small town family moves to the city, necessitating their reconstruction on a new and urban basis 10 (just as Negro literature today is full of personal breakdown in the great northern cities).

By other commentators on city life, the country is placed in the city, or the city in the country, in order to achieve comical, satirical, or wry effects. Kazin’s description of the Jewish slum of Brownsville (Brooklyn) is given punch by his description of the nearby countryside that is not countryside but a garbage dumping ground.11 In The Tunnel of Love, the hero indulges in fantasies of a rural hideout peopled with Hollywood-type girls and activities. A perennial delight to newspaper readers is the unexpected bit of country life found in the city: the fox that wanders down Lake Michigan into Chicago or the duck which hatched its ducklings atop a Milwaukee bridge near the center of town. Rural simplicity is self-consciously turned into sophisticated urbanity: thus Life magazine features an article, “Hick Tricks for City Slicks—Cute, Corny Styles Come in Ahead of Spring” : “A spring fashion that has come in early suggests the era when crackers came in barrels. Checked gingham, out-sized bows, stiff white shirt collars and bib-front dresses cut like a farmer’s overalls make fresh-faced city girls look something like oldtime country boys.” 12 Occasionally the city native laughs at himself, playing upon his reputed ignorance of country things, as when two old friends walking down Broadway perceive a flower, and one bending over to look at it asks what kind is it, and the other replies, “How should I know, I’ve been out of the millinery business for twenty years!” Some urban humor rests upon placing the sophisticated city person in a rural setting...