eBook - ePub

Daylighting in Architecture

A European Reference Book

This is a test

- 380 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

Typically one third of the energy used in many buildings may be consumed by electric lighting. Good daylighting design can reduce electricity consumption for lighting and improve standards of visual comfort, health and amenity for the occupants.As the only comprehensive text on the subject written in the last decade, the book will be welcomed by all architects and building services engineers interested in good daylighting design. The book is based on the work of 25 experts from all parts of Europe who have collected, evaluated and developed the material under the auspices of the European Commission's Solar Energy and Energy Conservation R&D Programmes.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Daylighting in Architecture by Nick V. Baker,A. Fanchiotti,K. Steemers in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Architecture & Architecture General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1

DAYLIGHTING EVOLUTION AND ANALYSIS

DAYLIGHTING AND BUILDINGS

Vision is by far the most developed of all our senses and throughout our cultural development light has been the main prerequisite for sensing our own world, and that of others - through painting, sculpture and literature.

The building of edifices for a whole range of functions, from simple shelter (which has enabled us to colonise almost all of the land surface of the globe) to ritual and ceremonial worship, and as instruments of state and government, has surely been the most significant of human activities and expressions of culture. It is not surprising then that the provision of light in buildings has been a fundamental concern of builders and designers - as fundamental as the building’s ability to modify climate or its structural stability.

Although we see daylight as the fundamental light source, it is interesting to note that artificial light sources have been present, in the form of fire, for as long as, if not longer than, the most primitive of shelters. However, up to most recent times man-made light was considered only as an alternative to the darkness of night-time. Now, quite suddenly in the last half century, the majority of the population of the developed world spend most of their working day, in schools, factories and offices, in artificial light. And much of their leisure, at home, in sports halls, shops and restaurants, also no longer relies upon daylight.

Recently, two issues have given us all cause for concern. Firstly the growing realisation that the energy use involved in the provision of artificial lighting contributes significantly to global environmental pollution, and secondly that the deprivation of daylight may have detrimental physiological and psychological effects on the occupants of buildings. These issues, together with architectural and aesthetic questions, make up the case for daylighting.

But has designing for daylight become a forgotten art? Can the skills of daylighting design be identified and disseminated, and what does science offer in support? These are the issues explored in the following chapters of this reference book.

Figure 1 - Modern mastery of daylight. Notre Dame de Haut, Ronchamp, France (Architect: Le Corbusier, 1954).

THE PRE-INDUSTRIAL PERIOD

Pre-industrial man had very different requirements from those of today - most of his time was spent outside tending the crops and animals. The earliest shelters were too primitive for any concern with the admission of light, the priority being protection from the life-threatening elements. Indoor domestic activities were simple and did not demand good lighting. It is in ceremonial and religious buildings that we see the earliest manifestation of conscious design for daylight.

The invention of glass had a crucial influence on the evolution of the window. Glass enabled the light and view-providing function to be maintained while insulating the interior, to some extent, from the external climate. This was of greater significance in the cooler climates of northern Europe than in southern Europe, where the presence of daylight more frequently coincided with a comfortable outside temperature. Nevertheless it was, as with many significant technical achievements, the Romans who first explored the thermal (as distinct from decorative) benefits of glazing their windows.

In medieval domestic architecture, the window pre-dates the use of glass but was equally important as a ventilation device to allow the smoke from the unfilled fire to escape. Indeed the word “window” in the English language derives from “wind eye”, and it is interesting that some of the earliest rules of orientation related to the sources of healthy and bad air, with particular concern for the plague, and not the sun. These openings were usually shuttered with internal hinged timber panels or surprisingly sophisticated sliding panels. The window opening was formed with vertical mullions which provided structural support, and limited the aperture size for security purposes.

Figure 2 - Late 16th Century farmhouse from Pendean, West Sussex, at the Weald and Downland Open Air Museum, Singleton. Indoor tasks made modest demands on daylighting - the small unglazed windows also provided ventilation.

The unglazed window, and the generally poorly fitting doors and shutters, led to a high infiltration rate. This was probably fortunate before the development of the flued fireplace, keeping pollution levels bearable. Internal temperatures would follow the external temperature quite closely and comfort was attained mainly by the radiant environment provided by the fire. This in turn gave little incentive to incorporate thermal insulation; glazing was needed to provide the crucial containment of internal air.

However, it was in sacred buildings that daylight first played the major role. The admission of light through the massive elements of the fabric carried symbolism which was irresistible to the architects of the great churches and cathedrals.

It was in sacred buildings too that glass made the earliest impact; the use of stained glass in the great cathedrals was widespread by the 12th century. The technique was pioneered in France and Germany and artisans from these countries often travelled Europe-wide to trade their wares and sell their skills. It is difficult to overstate the impact that a sunlit stained glass window, of majestic proportions, would have had on an illiterate peasant. Nowhere else would he see such colour, such brilliance and such richness of imagery. For the task of promoting religious beliefs, it was “state-of-the-art” media technology, remaining unchallenged for its visual impact until the cinema nine centuries later.

Figure 3 - 16th Century stained glass in King’s College Chapel, Cambridge. A Flemish glazier, using French glass, for an English King, - an early European venture.

Figure 4 - Church in Mdina, Malta, illustrates the ultimate in Baroque daylighting design.

Gradually glass manufacture became more established and costs came down. The land-owning classes were the first to adopt glazing, as violence and strife subsided, and the fortification of their dwellings became of lower priority. Windows began to be larger, and by the 16th century we see the secular celebration of the window, as typified by the oriel window in the Cambridge hall.

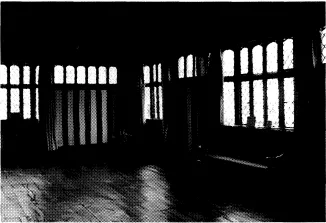

Figure 5 - Oriel window in the Master’s Lodge at Queens’ College, Cambridge (16th Century). The elaboration of the window indicated the importance of the people who dined adjacent to it.

Even before industrialisation, there were certain indoor activities that made real technical demands on daylighting. Writing, printing and painting all would have needed good light and, with only primitive artificial lighting available, there would have been a heavy reliance on daylight.

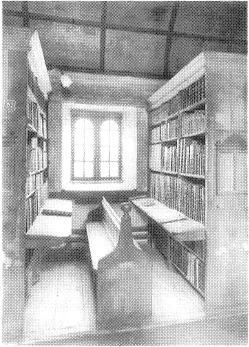

Figure 6 - Corpus Christi, Oxford, College Library 1604. The planning provides illumination for the bookstacks and the reading desks.

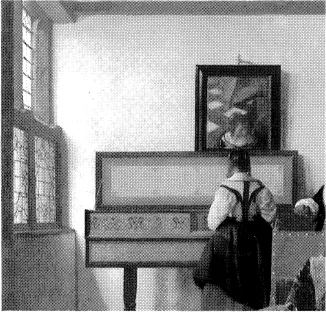

Figure 7 - Detail from Vermeer’s “The Music Lesson” (1662) showing the remarkably realistic rendering of the daylighting from the studio window.

It was in spinning and weaving that we see most impact on building design. The need for light would have meant that production was crucially dependent upon prolonging the availability of daylight to a maximum. It must be realised that in the 15th Century the real cost of artificial light (in relation to the cost of living) was about 6000 times (per lumen) more than today.

Figure 8 - Clerestory windows at the Guild Hall in Lavenham, UK, (c.1520). The timber-framed structure allowed large window areas, typical of many buildings in this region, famous for spinning and weaving.

Despite a steady increase in the use of glass in the 17th Century, mainly in the form of small leaded panes, total glazing areas remained small by modern standards. This was partly due to structural limitations, especially in masonry buildings, although in grand architecture amazing structural feats where achieved with stone and even moulded brick mullions. It was also due to method of manufacture, the crown glass technique, which produced panes of small size. Obviously the high cost of glass was also a constraint - the cottage homes of the rural peasant would still have their windows protected by oiled cloth or parchment.

Figure 9 - Hardwick Hall (Architect: Smythson, 1597) “More glass than wall”, built in Derbyshire, UK, for the Countess of Shrewsbury. The glass was made using sand and timber from the estate, by glass makers from the continent...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Acknowledgements

- Participating Institutions

- Preface

- Contents

- Introduction

- 1 Daylighting Evolution and Analysis

- 2 Light and Human Requirements

- 3 Daylight Data

- 4 The Photometry of Materials

- 5 Daylighting Components

- 6 Electric Lighting

- 7 Control Systems

- 8 Light Transfer Models

- 9 Evaluation and Design Tools

- 10 Integrated Energy Use Analysis

- 11 Case Study Analysis

- Glossary

- Appendix A: Sky Type Probability

- Appendix B: Daylight Availability

- Appendix C: Survey of Light Measuring Instruments

- Appendix D: Guide to Scale Models

- Appendix E: Survey of Control Systems

- Appendix F: Review of Design Tools

- Appendix G: Review of Computer Codes

- Appendix H: Artificial Skies

- Index