![]()

Introduction

Europe recovered and developed much more rapidly after World War II than after World War I. Clearly, American influence was an important part of this process, but its exact impact is still not clear. The Marshall Plan has traditionally been seen as a decisive turning-point, but many contemporary scholars argue that Europe revived spontaneously during 1945–6, and that American ‘dollars did not save the world’ in 1947–8. Similarly, the early postwar recovery apparently led into the long European boom of 1948–73, but it is still uncertain whether this boom was simply a natural rebound from interwar stagnation, or was caused by purposeful changes in European government policies, or was part of an international process in which American influence and example were predominant. Finally, since 1950 there has been obvious convergence around the North Atlantic basin, – not only in productivity and incomes, but also in social mores and political norms. The latter include the general adoption of competitive and meritocratic systems, the relative decline of class and national distinctions, the drift from socialism, and the weakening of the nation-state. To what extent were these due to immediate postwar American predominance, or to later American influences, or to purely European or general development processes that were bound to happen anyway?1

Scholarship on the Marshall Plan has moved through several stages. During the late 1940s and early 1950s there was a spate of analysis about US economic relations with Europe, generally emphasising the American contribution. However, most academic interest from the middle 1950s to the early 1980s focused on political problems, and especially on the origins of the Cold War. As part of this political analysis, it became received wisdom that, immediately after the war, the USA attempted global approaches to world economic problems. She helped to create the United Nations (UN), the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the other international organisations. She hoped that the wartime alliances with Britain, France and Russia would last, and that loans to individual countries would help to restore prosperity. She only became particularly concerned with Europe in early 1947, when the Potsdam settlement of 1945 began to fail, communist threats developed in Greece, Italy and France, and the postwar recovery faltered.2

This traditional version describes how the danger of Russian dominance over a bankrupt Europe forced the USA to act. Hence, on 12 March 1947 President Truman – referring to the communist insurrection in Greece – declared: ‘I believe that it must be the policy of the United States to support free peoples who are resisting attempted subjugation by armed minorities or by outside pressure.’ This became the Truman Doctrine. Then, on 5 June, General Marshall recognised in his famous Harvard Commencement address that:

Europe’s requirements … are so much greater than her present ability to pay that she must have substantial additional help, or face economic, social and political deterioration of a very grave character … Our policy is directed not against any country or doctrine but against hunger, poverty, desperation, and chaos.

This became the Marshall Plan.3

Political historians then went on to describe how the North Atlantic Alliance and the Marshall Plan secured and revived western Europe. By 1950, therefore, European output was well above 1938 levels. European integration began with the European Payments Union and the Schuman Plan of 1950, which helped to free European trade and integrate European heavy industry. By the mid-1950s Europe was becoming prosperous and in 1957 the Treaty of Rome created the European Common Market. The European economic miracle then continued until the crises of the early 1970s, by which time the United States, rather than the stronger European countries, was revealing economic weaknesses. Thus, the postwar American recovery programmes and the Marshall Plan were usually treated as successful or – for the conspiracy-minded – devious subsidiaries of the Cold War. For many years most economic historians gave them a parallel customary obeisance or ignored them almost completely.4

In the 1980s, however, as the Cold War faded, economic historians became more seriously concerned about the effects of American economic policy in Europe. Alan Milward in particular questioned the macroeconomic and socio-political importance of the Marshall Plan. He argued that Europe recovered very rapidly, using her own resources, in 1945–6; that the crisis of 1947 was marginal; and that European reconstruction and unity were achieved almost despite the Marshall Plan, not because of it. On the other hand, many writers like Michael Hogan emphasised the importance of American ideas and influences on Europe. These led to a widespread Americanisation and a new European neo-capitalism, but within limits. ‘But … these impressive gains notwithstanding …’, he wrote:

participating countries were not clay in the hands of American potters … They resisted the social-democratic elements in the New Deal synthesis, adapted other elements to their own needs and traditions, and thus retained much of their original form. In the beginning, the Marshall Plan had aimed to remake Europe in the American mode. In the end, [this] America was made the European way.5

More recently, historians have attempted to find compromises between these different views. Generally, economic historians accept Milward’s findings on the relative smallness, compared to GNP, of the Marshall Plan resource inputs. On the other hand, political historians have continued to emphasise the many favourable effects of American policy. They argue that it is difficult to understand how European recovery could have happened at the speed that it did without American assistance in opening trade channels and assuring investment. Some interesting research suggests that the American input was critical in sealing a very effective social contract post-1945. The aid may have been small compared to GNP, but it was sufficient to clinch productive deals between many old enemies, economic, social and national. In the 1920s this widespread social consensus never really happened. Post-1945, with better-planned American aid, it did – and everyone gained. This book surveys the debate between these points of view.6

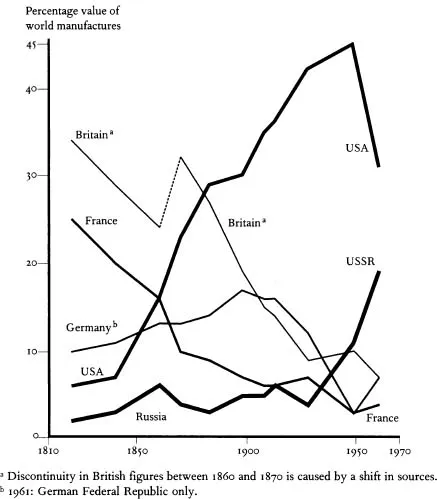

American dominance was the unifying factor underlying the whole period 1945–60. Figure 1.1 shows that America was producing about 40% of world manufacturing at this time, a proportion never equalled before and unlikely ever to be achieved again. In the late 1940s American industry appeared so technically advanced that it seemed as if Europe would never be able to catch up. This predominance was partly a function of long-term trends dating from the mid-nineteenth century, partly the temporary results of the war. But, however caused, it gave the USA an extraordinary temporary leverage in Europe. If ever there was a time when the USA should have been able to influence international affairs, it was then. After about i960 Europe (and East Asia) began to catch up and American dominance waned.7

Figure 1.1 American Share of World Manufacturing (% distribution), 1820–1961

Sources: For 1820–60: Michael G. Mulhall, Dictionary of Statistics (London, 1909), p. 365; for 1870–1929: League of Nations, Industrialisation and Foreign Trade (Geneva, 1945), p. 13; for 1948–61: United Nations, The Growth of World Industry, 1938–1961 (New York, 1965), pp. 230–76.

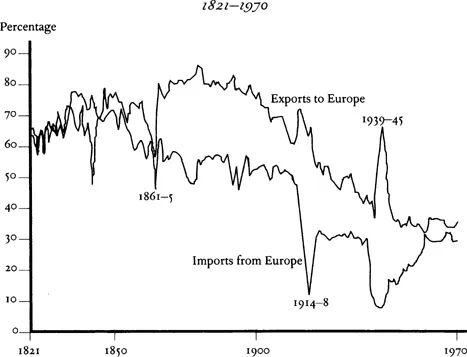

A major symptom of American power in international economic relations in the early twentieth century was the ‘dollar gap’. Figure 1.2 shows the American–European trade deficit over the very long term. Exports and imports from Europe are shown as a % of total US exports and imports. The measure therefore conceals both the huge growth in trade volume across the Atlantic and the absolute size of the gap, but it does show the relative size of transatlantic, as against total American, trade and the relative size of the European trade gap. Until 1860, American trade with Europe was a very high proportion of total US trade and was more or less balanced. From 1865 onwards, however, US imports of European goods declined relatively as the USA industrialised and began to buy raw materials a.nd luxuries from Canada, Latin America and Asia. High American tariffs insulated the US market even further.8

On the other hand, American exports of cotton, wheat, oil and the ‘high tech’ goods of the time, such as cars, cameras, and machine tools, grew very rapidly. Britain in particular needed the food and raw materials and had low tariffs. The USA found that she could ‘free ride on British free trade’ without fear of retaliation. The other European nations were less exposed, but generally had trade deficits with the USA. Towards 1900 the deficit declined – as relatively less American wheat was shipped – but it then expanded enormously in World War I as the allied war effort drew in American supplies. Before 1914 the deficit was covered by emigrant remittances, receipts from such European services as shipping and insurance, and the earnings of those European empires and Third World countries which had deficits with Europe, but surpluses with the USA. India, for instance, had a deficit with Britain, but a surplus with China and Japan, which in turn had surpluses with the USA. During World War I the gap was covered by such extraordinary measures as the sale of British-owned American railroad securities and American loans.9

In the 1920s high American productivity and tariffs still excluded most European goods, and the consequent deficits continued to be covered in roundabout ways – usually through Third World, empire or service earnings. Britain’s colony Malaya, for instance, sold rubber and tin for use in American cars. The Dutch East Indies sold oil to the USA. The British and Norwegians provided freight. Italy and France earned dollars from wealthy American tourists and expatriates; Italy also received large immigrant remittances. In the late 1920s the balance was covered by American loans. When these dried up in 1929, the European nations, pressed by depression, resorted to a great variety of national and imperial trade and exchange controls. All the European countries, for instance, reduced their US cotton and grain imports and attempted to find alternative sources.10

Figure 1.2. American Trade with Europe (as % of total US trade), 1821–1970

Source: United States, Bureau of the Census, Historical Statistics of the United States: Colonial Times to 1970 (United States Government Printing Office: Washington, DC, 1975), pp. 903–7.

Transatlantic trade collapsed in the 1930s, but recovered dramatically during and after World War II. The share of transatlantic trade in total US trade continued to decline until about 1950 and then stabilised. There was a last great expansion of the gap, 1939–50, before it finally closed. Lend-Lease – the free pooling of all allied supplies during the war – covered the British trade deficit until 1945, but the postwar years were especially difficult for Europe. The leading countries had lost, or were about to lose, their empires and Third World surpluses which had hitherto funded the gap. They had also lost most of their investment, shipping and other invisible earnings. Yet they desperately needed American supplies and machinery to re-equip.

It was therefore the main function of the Marshall Plan to help the European nations through this difficult transition. They were encouraged to copy American production methods, to expand exports to America and to increase intra-European trade. Even Britain was eventually pulled into the European orbit. However, Figure 1.2 suggests that, to a certain extent, the Marshall Planners were swimming with the tide. Underlying technical developments – the spread of American technology, the displacement of certain raw materials (like cotton), the growth of European agriculture – all tended to reduce European dependence on America. Europe had good chances of success, whatever the external assistance. (The dollar gap is discussed in Chapter 2, and its decline in Chapter 15.)

In the immediate aftermath of the war, the degree of imbalance with the USA seemed overwhelming. The Europeans knew that they would need huge quantities of North American food, raw materials and machinery to rebuild their economies. Many of the alternative supplies had been destroyed or had dried up. Tight import controls and deflation at home might limit demand, but the 1930s depression had convinced leading economists such as Keynes that planned autarchy was self-defeating. The Bretton Woods debates about postwar financial and commercial organisation – held in New Hampshire in 1944 – therefore revolved around the likely USA–European trade deficits and how to accommodate them with reasonably free trade. All liberal economists wanted to avoid the excessive controls of th...