![]()

1

INTRODUCTION

History and Philosophy of Treatment in Dementia

Michelle S. Bourgeois and Ellen M. Hickey

Clinicians from many disciplines have ventured to provide appropriate and effective interventions for the diverse behavioral symptoms that define the neurologically degenerative condition known as dementia. Problems with memory in older adults have been described for thousands of years, with the medical community describing changes in cognitive, psychiatric, and intellectual functioning that were not common features of aging. In addition to dementia, other terms for similar behavioral symptoms included amentia, dotage, imbecility, insanity, idiocy, organic brain syndrome, and senility (Boller & Forbes, 1998; Torack, 1983). The first edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM; American Psychiatric Association [APA], 1952) described dementia as an organic brain syndrome (OBS) that was differentiated from an acute brain syndrome due to its chronic and irreversible nature (Boller & Forbes, 1998). Subsequent editions of the DSM reflected the evolution of terminology from OBS to senile and presenile dementia to the current major neurocognitive disorder (NCD), which is defined as “a decline from previous level of performance in one or more cognitive domains (memory impairment, abstract thinking, personality, judgment, language, praxis, constructional abilities, or visual recognition) that interferes with independence in work, social activities, and relationships with others” (5th ed.; DSM-5; APA, 2013).

As early as the 15th and 16th centuries, the cause of “insanity” was attributed to syphilis, and was referred to as general paresis of the insane or neurosyphilis. The late 19th and early 20th centuries brought a more precise and analytic approach to the differentiation of clinical symptoms. As clinicians observed and documented the specific characteristics of individuals, new diagnostic classifications emerged. In 1892, Arnold Pick described one of the pathologies that causes frontotemporal lobar degeneration. Alois Alzheimer published the first account of Alzheimer’s disease in 1906. Kraepelin differentiated “senile” and “presenile” forms of dementia in 1910 (Amaducci, Rocca, & Schoenberg, 1986). “Cortical” and “subcortical” dementias were first proposed by Von Stockert in the 1930s to describe lesions appearing in the brain stem and deep gray matter (Whitrow, 1990). Primary degenerative dementias became the popular nosology in 1980, with the third edition of the DSM (APA, 1980) (3rd ed.; DSM-III; APA, 1980). Advances in neuroimaging and neuropathology, as well as in the clinical fields of neuropsychology and speech-language pathology (SLP), have resulted in considerable evolution of our understanding of the heterogeneity of diseases that cause dementia syndromes. Dementia with Lewy bodies, corticobasal degeneration, subcortical gliosis, frontotemporal dementia, primary progressive aphasia, and HIV-associated dementia are some of the most recently identified diseases that cause dementia syndromes (5th ed.; DSM-5; APA, 2013).

The recognition of a disease was soon followed by the identification of treatments for the undesirable symptoms. The earliest accounts of intervention for dementia symptoms were the use of a rotating chair, which was suggested for mental conditions related to congested blood in the brain, and the hyperbaric oxygen chamber, thought to re-oxygenate brain tissues causing dementia (Cohen, 1983). Julius Wagner von Jauregg, the first psychiatrist to win the Nobel Prize, discovered in 1917 that malaria inoculations improved six of nine patients with neurosyphillis (Whitrow, 1990). Recently, pharmacologic therapies have provided small benefits for improving cognition, including cholinesterase inhibitors (e.g., donepezil) for persons with mild-moderate Alzheimer’s dementia, and a N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor antagonist (memantine) for persons with mild to severe Alzheimer’s dementia (Farrimond, Roberts, & McShane, 2012; Tan et al., 2014), but it is unclear if these treatments are effective for persons with atypical dementias (Li, Hai, Zhou, & Dong, 2015). When behavioral disturbances including depression, agitation, aggression, and hallucinations require treatment, clinicians sometimes try a variety of neuroleptic, antidepressant, anxiolytic, and anticonvulsant medications, but not without risk of serious side effects (Corbett, Burns, & Ballard, 2014; Reus et al., 2016).

Research and policy development have encouraged a person-centered care approach (Kitwood, 1997), which resembles the kind of care and quality of life that most people would choose if given the opportunity. Person-centered care is anchored in values and beliefs that return the locus of control to older adults and their caregivers to support their quality of life (QoL). The main tenets of person-centered care call on care providers to promote choice, dignity, respect, self-determination, and purposeful living. The growing emphasis on person-centered (Kitwood, 1997; Ryan, Byrne, Spykerman, & Orange, 2005) resulted in a culture change in models of long-term care, and governments began to legislate more holistic care. The United States Congress passed the Omnibus Budget and Reconciliation Act of 1987 (OBRA; American Health Care Association, 1990) that mandates physical, cognitive, and communicative evaluations of residents, the development of a care plan upon admission to a nursing home, and periodic reassessments. When deficits in cognitive and communicative functioning are identified, the plan of care should include referral to the speech-language pathologist (SLP) for further assessment of treatment needs.

The past few decades have seen an explosion of interest in holistic and nonpharmacological approaches to intervention, which is ideally provided by an interprofessional team of healthcare professionals, with the person with dementia and family at the center of the team. Speech-language pathologists have only begun to develop assessment and treatment approaches for the cognitive and communication deficits that accompany dementia in the past 30 years (Bayles et al., 2005). Bayles, Kaszniak, and Tomoeda (1987) first documented the cognitive-linguistic deficits and skills of persons with dementia across the stages of brain degeneration, providing the resources that clinicians needed to assist in the differential diagnosis of people presenting with dementia symptoms. At that time, when a person was diagnosed with a degenerative neurological condition, the role of the SLP was to direct the family to supportive services in the community, including nursing homes.

From the mid-1980s, when behavioral treatments for the language and cognitive deficits of persons with dementia began to appear, thoughts about therapeutic intervention began to shift from futile to possible (Hopper, 2003). Evidence began to document the presence of spared abilities that could be used to design effective cognitive-communicative interventions that support or modify the client’s behaviors directly (e.g., Camp, Foss, O’Hanlon, & Stevens, 1996; Hopper, Bayles, & Kim, 2001) or to assist caregivers to change their own coping strategies and behaviors (e.g., Bourgeois, Schulz, Burgio, & Beach, 2002). Effective nonpharmacological interventions to reduce responsive behaviors and to compensate for cognitive deficits include: direct interventions (person-centered care, communication skills training, redirection techniques, social and activity stimulation); environmental modifications; and caregiver education (e.g., Cohen-Mansfield, Thein, Marx, Dakheel-Ali, & Freedman, 2012; Hopper et al., 2013; Livingston et al., 2014). Psychological treatments can help to decrease depression and anxiety in persons with dementia (Orgeta, Qazi, Spector, & Orrell, 2014). Finally, exercise by people with dementia may improve performance of activities of daily living (ADLs) (Forbes, Forbes, Blake, Thiessen, & Forbes, 2015).

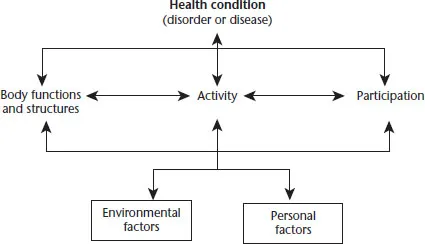

As noted above, caring for persons with dementia saw a major shift with the development of social models of health and disability. The World Health Organization developed the International Classification of Impairment, Disability, and Handicap (ICIDH; WHO, 1980), which evolved into the International Classification of Functioning, Disability, and Health (ICF; WHO, 2001). The ICF guides clinicians in understanding the effects of a medical condition on an individual, while examining how the person’s context influences level of disability and functioning. The ICF can be used with individuals or populations to facilitate holistic approaches for assessment and intervention for people with chronic conditions. Figure 1.1 depicts the ICF components as (a) impairments of body structures and functions, (b) activity limitations related to the execution of a task or action, and (c) participation restrictions that limit involvement in life situations. These components are influenced by a variety of environmental and personal factors that act as supports or barriers to meaningful participation.

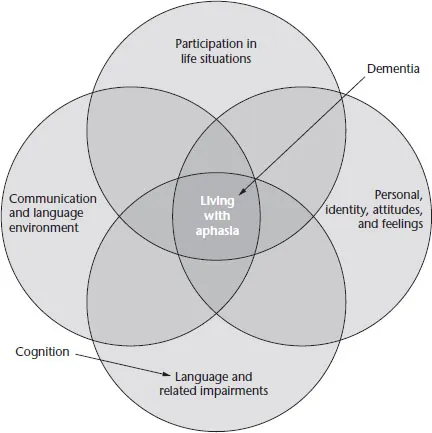

Within the field of speech-language pathology, the ICF (WHO, 2001) has inspired development of frameworks for communication disability and participation (e.g., Baylor, Burns, Eadie, Britton, & Yorkston, 2011; Threats, 2006, 2007). The Living with Aphasia: Framework for Outcome Measurement (A-FROM; Kagan et al., 2008) is an integrated, social model that was empirically derived from focus groups and visually depicts the relationship among impairment, participation, personal factors, and the environment. Personal values, identity, and feelings are given equal weight when compared to the impairment itself (see Figure 1.2). Although designed for people with aphasia, the domains of the model can easily be applied to life participation of individuals with dementia as well. Indeed, the goal of treatment for persons with dementia is improvement of the lived experience, as noted in the center most section of Figure 1.2. One of the many useful components of this model is that it urges clinicians to consider conversation as an ADL, and to recognize that context is key in working on communication. These elements can be applied to our work with persons with dementia in the form of a life participation approach for dementia.

FIGURE 1.1 The International Classification of Functioning, Disability, and Health

Source: ICF; WHO, 2001.

FIGURE 1.2 Living with Aphasia: Framework for Outcome Measurement (A-FROM) Adapted for Use as a Life Participation for Persons with Dementia Model

Source: Adapted with permission from the Aphasia Institute, Toronto, Canada. Kagan, A., Simmons-Mackie, N., Rowland, A., Huijbregts, M., Shumway, E., McEwen, W., Threats, T., & Sharp, S. (2007). Counting what counts: A framework for capturing real-life outcomes of aphasia intervention. Aphasiology, 22(3), 258–280.

Other social models have been developed to explain responsive behaviors of persons with dementia, and to promote development of person-centered care that maximizes functioning and quality of life. Some models aim to explain responsive behaviors as reflecting the theory of “unmet needs” (e.g., Algase et al., 1996; Kunik et al., 2003). These models encourage us to identify interventions for unmet needs of the person with dementia by examining the person, the caregivers, and the environment to improve quality of life for people with dementia and their caregivers (see Chapter 3 for details), and applied in the assessment and intervention chapters (see Chapters 6–8). The evolution in philosophy of care and policies regarding care has sparked a new attitude toward working with persons with dementia, with an increased focus on maximizing independent functioning and participation for as long as possible and on enhancing the quality of life of persons with dementia as well as their caregivers (Bourgeois, Brush, Elliot, & Kelly, 2015). These models have contributed to our guiding principles for intervention for persons with dementia, which will be explained in Chapter 4 and applied throughout the intervention chapters.

Assessment instruments have been designed to identify not only the degree of impairment and the resulting activity limitations and participation restrictions, but also to determine the preserved strengths of an individual that can be used to develop interventions to address person-centered, meaningful goals (see Chapter 5 for more details). Interventions can target any aspect of the ICF. Impairment-based interventions for persons with dementia are primarily pharmacological interventions, and some behavioral interventions. Other interventions aim to improve participation and engagement in meaningful activities. The development of two innovative approaches has shaped the way that the interprofessional team provides care for persons with dementia: the strength-based needs approach (e.g., Eisner, 2013) and Montessori-based approaches (e.g., Bourgeois et al., 2015; Camp & Skrajner, 2004; Elliot, 2011). These approaches encourage care providers to view persons with dementia...