- 357 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Howard S. Becker is a leading contemporary sociologist who interprets society as collective action and sociology, therefore, as the study of collective action. This volume explores the theory and methods necessary to study collective action and social interaction. Becker includes most of his work on theory and method that has not previously appeared in book form. It reflects his unique way of thinking about and studying society.The first part of the book treats methodological problems as problems of social interaction and lists a series of research problems requiring analytic attention. The second part illustrates Becker's approach through full reports on two of his major research projects. Four theoretical statements on how people change comprise the third part, and the fourth part includes important contributions to the study of deviance. These essays illustrate the need to study deviance as part of the general study of society, not as an isolated specialty.Sociological Work is an important statement of the distinctive theoretical and methodological views associated with the Chicago School of Sociology; it shows a deep concern with the first-hand study of processes and human consequences of collective action and interaction. This illuminating volume is an engaging introduction to some of the issues of importance to sociologists and those interested in the studies of collective action and deviance, and it is well adapted to use in courses in these areas.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Topic

Sciences socialesSubtopic

Féminisme et théorie féministePART I

Problems of Sociological Method

CHAPTER ONE

On Methodology

Methodology is too important to be left to methodologists.

By that trite paraphrase of a cliché I mean a distinction that will be clearer when I define the terms. Methodology is the study of method. For sociologists, it is presumably studying the methods of doing sociological research, analyzing what can be found out by them and how reliable is the knowledge so gained, and attempting to improve these methods through reasoned investigation and criticism of their properties.

One might say that methodology so defined is every sociologist's business insofar as he participates in doing research or in reading, criticizing, and teaching its results. That is surely true. Yet we have courses in methodology that some, but not all, sociologists teach. We have an official Section on Methodology of the American Sociological Association, to which some, but not all, sociologists belong. In short, some sociologists are methodologists while others are not, which is to say that in some institutional sense methodology is not every sociologist's business, whether it ought to be or not, whether in fact it is or not. The question then arises as to whether methodologists—the institutionally accepted guardians of methodology—deal with the full range of methodological questions relevant for sociology, or whether they deal with a non-randomly selected subset (as they might say) of those questions.

Obviously, I raise that question because I believe methodologists do not deal with the full range of questions they ought to. Instead, they attempt to influence other sociologists to adopt certain kinds of methods; in so doing they leave practitioners of other methods without needed methodological advice and fail to make an appropriately full analysis of the methods they do consider. I do not make that harsh judgment in a quarrelsome way. I am less concerned with proving that methodologists have done wrong than with improving methodological practice by removing some of the presently uninspected barriers between methodology and research.

I first take up the question of the limits of conventional methodology, demonstrating (what may be obvious) its predominantly proselytizing character. Then I consider alternative modes of methodological discourse, including some that were they more commonly used might improve our overall methodological prowess. Finally, I discuss some important questions of method that now suffer from the lack of sustained methodological inquiry.

Methodology as a Proselytizing Specialty

Although some distinguished methodologists and philosophers of sicence believe that methodology should devote itself to explicating and improving contemporary sociological practice, conventional methodology does not ordinarily do so. Rather, it devotes itself to telling sociologists what they should be doing, what kinds of methods they should be using, and suggests that they either study what can be studied by those methods or busy themselves figuring out how what they want to study can be turned into what can be studied by those methods. I call methodology a proselytizing specialty because of this very strong propensity of methodologists to preach a “right way” to do things, because of their desire to convert others to proper styles of work, because of their relative intolerance of “error”—all these exhibiting the same self-righteous assurance that “God is on our side” that we associate with proselytizing religions.

What brand of salvation does methodology sell? What do they propose as the proper path to better science? The details vary and indeed show a tremendous amount of faddishness. At one moment we may be assured that only through the use of strict experimental designs in controlled laboratory conditions can we achieve rigorously tested scientific propositions. A year later, someone else enjoins us to pay more careful attention to our sampling procedures, lest our conclusions turn out to be inapplicable to any larger universe. Some bemoan the failure of sociologists to replicate earlier studies, and others recommend more extensive use of statistical models of causal inference, path analysis, mathematical models, computer techniques—each has its champions.

Beneath this surface diversity, one can easily discern a common pattern: a concern for quantitative methods, for the a priori design of research, for techniques that minimize the chance of getting unreliable findings due to uncontrolled variability in our procedures. Is it too extreme to say that methodologists would like to turn sociological research into something a machine could do? I think not, for the procedures they recommend all have in common the reduction of the area in which human judgment can operate, substituting for that judgment the inflexible application of some procedural rule.

That substitution clearly has much to recommend it, for you cannot have a science when propositions can be asserted with no more warrant than “it looks that way to me.” Such assertions are notoriously subject to all sorts of extraneous influences, especially wishful thinking. And propositions generated by more scientific procedures may still be subject to those influences at every point where what is to be done is left unspecified. Thus, a fully specified sampling procedure, machinelike, is better than quota sampling, which leaves the choice of which middle-aged white males to interview to the interviewer, and thus to whatever nonrandom biases might affect what the interviewer does, with the danger that those biases are correlated with the attitudes under study. If an interviewer, fearing rejection, picks “nice” people and that “niceness” is correlated with liberal political attitudes, for instance, then the unspecified sampling procedure can produce distorted results in a way true probability sampling does not allow.

So science-as-machine-activity has much to recommend it, ruling out all sorts of uncontrolled biases. But, as is well known, it is difficult to reduce science to such strict procedures and fully worked out algorithms. Confronted with this difficulty, we can take one of at least two courses. Rather than insisting on mechanical procedures that minimize human judgment, we can try to make the bases of these judgments as explicit as possible so that others may arrive at their own conclusions. Or we can transform our problems into problems that can be handled by machinelike procedures. Or we can decide not to study problems that cannot be so transformed, on the ground that we had best apply our limited resources to problems that can be handled scientifically. Contemporary methodologists have by and large chosen the latter course.1

We might think their choice reasonable, if it were not that most working sociologists do not accept it. The people who do sociological research often accept, even champion, the methodologist's general tendency to push for more “rigorous” methods. But they will not accept his implicit recommendation not to do what cannot be done in that rigorous way. Though they respect the methodologist's achievements, they respect other achievements as well. And these other achievements are accomplished by methods that conventional methodology, not particularly approving of them, has had little to do with formulating, criticizing, or improving.

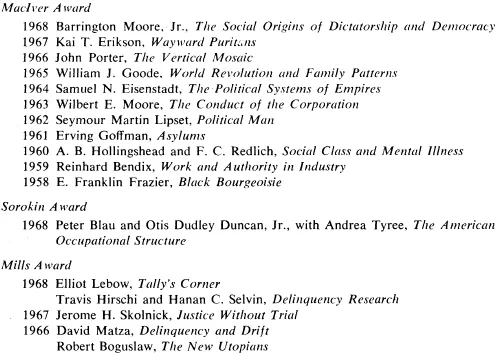

Let me propose a simple test of what Richard Hill has spoken of as the “relevance of methodology.”2 We can take the chairmen of the ASA Section of Methodology to represent those sociologists whose methodological work is especially respected, the true carriers of the methodological tradition. And we can take those books that have received one of the three major prizes awarded in sociology—the MacIver, Sorokin, and Mills awards—to represent kinds of sociological analysis generally thought worthwhile. How many of the methods used to produce prize-winning books could one have learned by studying the methods associated with the chairmen of the Section?

Tables 1.1 and 1.2 list the chairmen of the section since its founding in 1961 and the winners of the major awards since their founding dates. Without characterizing the work of the section chairmen in individual detail, we can safely say that they have all been associated with methodological work of the restricted kind I have described: methods of survey research, statistical analysis, sampling, and the use of mathematical models. By studying such methods one could clearly have learned to produce some of the prize winners: Blau and Duncan's American Occupational Structure, Hirschi and Selvin's Delinquency Research, the Hollingshead-Redlich study of Social Class and Mental Illness, showing that methodologists are not entirely without honor in their own country. But many more of the prizewinners used methods our most honored methodologists have spent little time on. The point is not that methods recommended by methodologists are bad because they have produced relatively few prizewinners. (A persistent rumor suggests that prejudice has operated to keep the number low.) I mean only to say that some methods they do not ordinarily discuss or recommend also produce high quality work.

Methodologists particularly slight three methods used by prizewinners. They seldom write on participant observation, the method that produced Skolnick's Justice Without Trial and Goffman's Asylums. They seldom write on historical analysis, the method that produced Erikson's Wayward Puritans and Bendix's Work and Authority in Industry. And they seldom write on what few of us even perceive as a method—the knitting together of diverse kinds of research and publicly available materials which produced Frazier's Black Bourgeoisie. All three methods allow human judgment to operate, unhampered by algorithmic procedures, though they all allow the full presentation of the bases of those judgments that satisfies scientific requirements.

Table 1.1Winners of Major Sociological Awards

I propose, then, that methodologists have failed us because in their effort to reduce human sources of error they have ignored what a great many sociologists do and think worth doing. They have thus ignored extremely important methodological problems, problems that affect even the methods they recommend. When methodologists apply their talents to the full range of problems that afflict us, making use of a full range of analytic techniques, then methodology will achieve that usefulness to working sociologists it ought to have had all along.

Table 1.2Chairmen of the Section on Methodology, American Sociological Association

| 1968–69 Hanan C. Selvin | 1964–65 Peter H. Rossi |

| 1967–68 H. M. Blalock, Jr. | 1963–64 Sanford Dornbusch |

| 1966–67 Richard J. Hill | 1962–63 Herbert Hyman |

| 1965–66 Robert McGinnis | 1961–62 Leslie Kish |

Modes of Methodological Discourse

Sheer technical description constitutes the first and most primitive form of methodological writing in sociology. Such writings are really no more than “how to do it” treatises, describing what practical men in our discipline have found to be useful ways to do research. They may be more or less logically described, but the ways described do not arise out of any particularly profound analyses of the problem at hand. The problem has, rather, been viewed as a practical one about which something needs to be done so that research can go forward. The writer describes something he tried and found to “work,” whatever that may be taken to mean.

What I include in this category will be clear enough shortly, when I describe the other kinds of methodological writing it is not. But some examples may be helpful. They are found in writing about all the varieties of methods used by sociologists. For example, the technical innovations in handling qualitative field notes proposed by Geer and myself represent a tentative solution to a problem that had annoyed field workers for some time and for which most of them had already devised schemes of their own.3 Similarly, many techniques of survey analysis or of getting surveys done in the field are described in works of this kind.

It may, perhaps, mean something that technical description does not often appear in the published literature, but rather is handed on by word of mouth, as a kind of oral tradition. Since this kind of technical material frequently has little or no logical or theoretical basis, it somehow seems too crude to publish. Professors tell their graduate students how to handle the problem, considering the whole thing part of the “art of sociology.” Or colleagues working in the same area may pass on tips about useful ways to proceed. When these materials do find their way into print, they are often denigrated as “mere cookbook” stuff.

I mention technical description because this earthy form of knowledge is probably the precursor of a more systematic approach to methodology we can call analytic. Analytic writing attempts to discover the logic inherent in conventional practice, in order to reduce that practice to a defensible set of rules of procedure. The analytic methodologist assumes, in effect, that if some sizable number of sociologists do something in some particular way they probably have, by some means or another, blundered on to an essentially correct method, which now needs to have its logical structure laid bare. By uncovering that structure, we can sort out what is logically inherent in the method and what is only attached to it by circumstance or custom and can safely be ignored or, better, be done in a more useful and sensible way.

Analytical methodology arises out of dissatisfaction. A sociologist may feel it beneath his dignity as a scientist to work by conventional rules of thumb. His methods may not work as well as he would like them to. He may begin to explore the underlying logic of what he is doing from simple intellectual curiosity or because someone has attacked it.

In any event, analytic methodology characteristically takes the form of asking what real sociologists do when they do research and then tries to see what logical connection can be made among the various steps in the research process. Asking why things are done in a certain way, it develops a logically defensible description of what had perhaps before been only a collection of customary practices. We can then improve everyday practice by designing research activities according to what they should be in order to play their proper role in the method as it has been analyzed.

For instance, the dissatisfaction of the “Columbia sch...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Preface

- Table of Contents

- Part 1. Problems of Sociological Method

- Part 2. Educational Organizations and Experiences

- Part 3. The Processes of Personal Change

- Part 4. Deviance

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Sociological Work by Fanny Ginor in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Sciences sociales & Féminisme et théorie féministe. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.