![]()

Part I

Living Together

![]()

1

Ideas of the Suburb

In our lived experience, city and suburb go together, much like ‘horse and carriage’. Maybe this was the general rule in the mid- to late-twentieth century. ‘You can’t have one without the other’ ran the refrain in the theme song to the television production of Thornton Wilder’s Our Town in 1955. This places the song in what most historians regard as the first wave of the age of the suburb, though in defining that age, none of them give the suburb equal weight to the city centre. The central business district is regarded as the prime mover. But, just as the absolute coupling of ‘love and marriage’, the theme of the song has come to be challenged and redefined, so we think the relationship between suburb and city postulated in the second half of the twentieth century needs a new look and is ripe for the emergence of new architectural forms.

Historians we admire (we do not claim to be comprehensive in our citations, nor exhaustive, we simply offer up readings and precedents that have caught our imaginations) frame the project for us, even as we note their blind spots. In his 1998 book, Cities in Civilisation, geographer/town planner Peter Hall1 (1932–2014) begins a discussion of the suburb on page 965. There he asserts that the suburb ‘began in North America, the UK and Australia in the 1950s … and spread to all of Western Europe, even [our italics] Italy and Spain …’.2 We note the tone of surprise and we challenge the history. The suburb began much earlier than this. Architect and theorist, Mario Gandelsonas, looks a little more closely and argues that the ‘opposition between city and suburb’ emerges forcefully following the Second World War, even though, ‘in the US, suburbs can be dated to 1815 in Boston, Philadelphia and New York … as people pursued the symbolic “house in the country” …’.3

This urbanite dream of ‘a house in the country’ may be a peculiarly Anglo-Saxon ideal—or so argued Raymond Williams.4 He pointed out that every Frenchman dreams of living in Paris, while every Londoner goes to sleep longing to be in the country. Actual examples of this bucolic/urban ideal emerge in England shortly before they do in North America. Horace Walpole built Strawberry Hill, his dream country house, in Twickenham outside London, moving there in 1749. Once settled, his

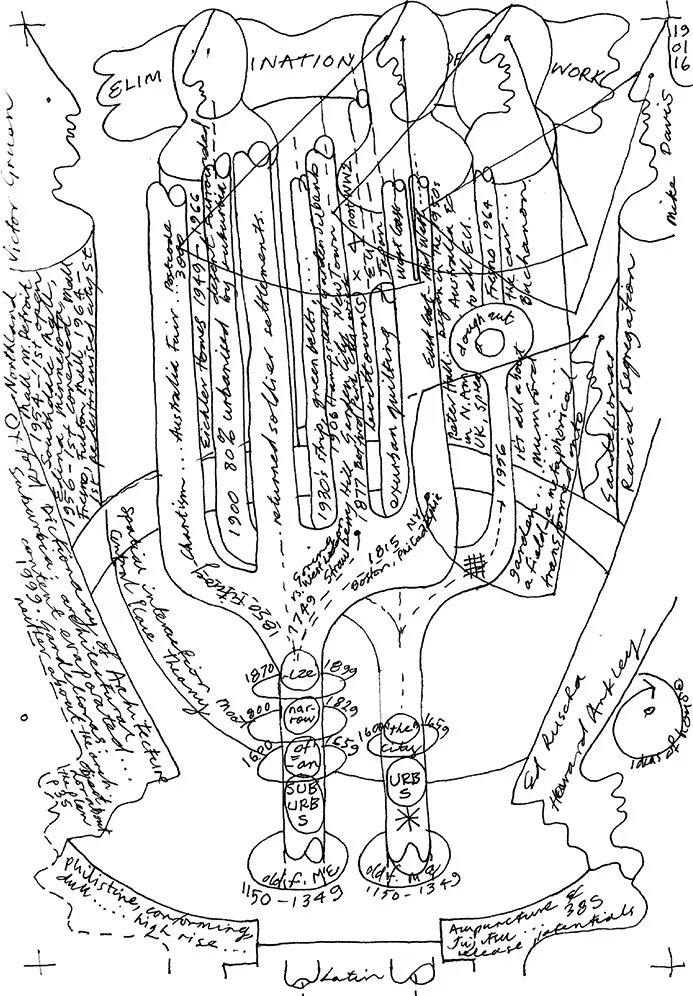

Figure 1.1 Leon van Schaik: Ideogram Plotting the Topics Covered in this Chapter. This shows ideas of suburbs in two overlapping trees, with key theorists looking on from the margins.

daily routine included an afternoon trip to the city centre, presenting an exalted ideal of suburban living. Walpole recorded beginning his day with a late breakfast, then directing works on his house and garden, departing in a ‘light carriage’ to go to his city centre club and return for dinner by four o’clock that afternoon.5 Thomas Jefferson—whose house dwells in the imaginations of so many of us, particularly the wall bed opening either to his study or to a dressing room—began building Monticello in 1768, arguably the apex of the North American ideal of a house in the country.

European invasion and settlement of Australia began in 1788, but the way it was settled presents another challenge to the idea that suburban living began after the Second World War. Melbourne’s suburban culture has been celebrated and exported around the world through the TV series Neighbours (first broadcast in March 1985), corroborating the post-1950s view of suburbia, yet the ‘city’ of Fitzroy was subdivided in 1850, Melbourne’s first suburb.6 It had an eighteenth-century cast to it, in that it housed a complete range of income earners. Subsequently, more demographically uniform suburbs were the engines by which at the end of the nineteenth century, 80 percent of Australia’s population was living in the capital cities of the various colonies that were to comprise the Commonwealth of Australia. While the dream of a rural haven impelled northern development of the ‘garden city’ kind, in Australia the impulse was more political, driven by individual desires to be as independent of the state as possible. The equal rights ideals of the Chartists were forcefully exported to Australia after they were supressed in England, and lie as the usually unstated (Hugh Stretton is the exception) political bedrock at the core of our suburbia-philia.

Such a love is unusual. As etymology alone indicates, cities and suburbs predate the English language, finding their origins in French and in Latin. Their core meanings are described in the Shorter Oxford English Dictionary: city ‘2. a large town, spec. a town created a “city” by charter, esp containing a cathedral’; and suburb ‘1. a district especially residential lying immediately outside or (now) within the boundaries of a city’; ‘2. the parts about the border of any place, the outskirts’. Both words, city and suburb, come into the language in its Middle English form and in the same period (1150–1349). By 1350–1469 ‘a suburban’ means a resident of a suburb, and ‘outer suburb’ is in use. ‘Suburban’ meaning ‘of a suburb’ follows in 1600–59, well before Walpole made his move. ‘Suburbicarian’ and ‘suburbanity’ emerge in ‘M19’—1830–69 when Dickens was writing about suburban living; ‘suburbanism’, ‘suburbanite’ and ‘suburbia’ in ‘L19’ join them in 1870–99. ‘Suburbanise’ arrives in ‘L19’ too, while ‘suburbanisation’ arrives in ‘E20’ (1900–19). This verb is preceded by ‘the adjective suburban’ meaning ‘narrow minded, provincial’ (1800–29). None of this will surprise readers of English novels, many will recall in Great Expectations (1862) Charles Dickens’ description of Mr Wemmick’s suburban ‘castle’, a minute ‘republic of pleasure’7

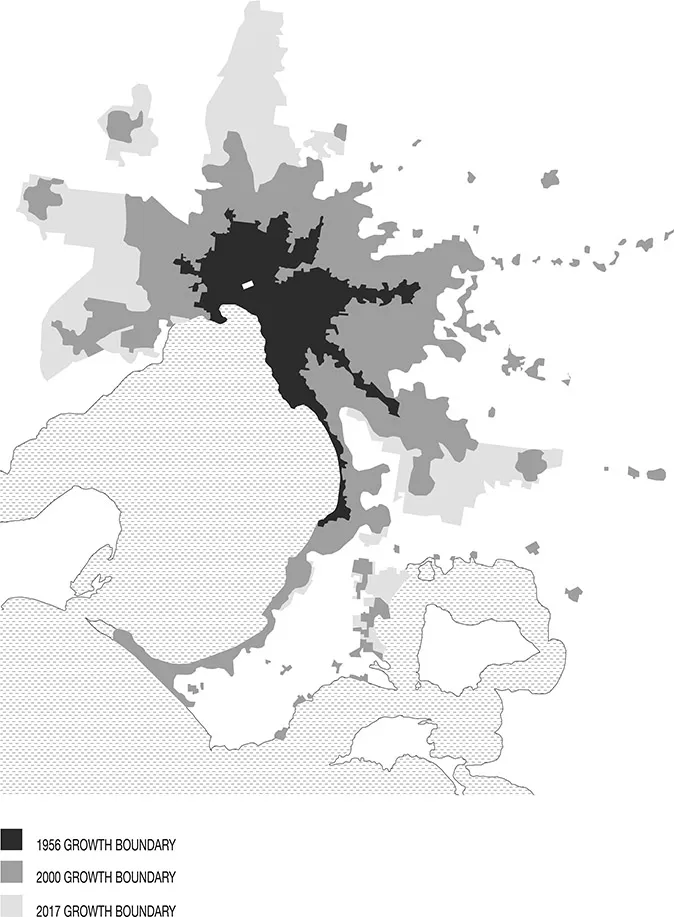

Figure 1.2 Melbourne City and Suburbs. Overall extent in relation to Port Phillip Bay and Central Business District, 1956, 2000 and 2017.

replete with tiny moat and drawbridge. So pervasive are the negative connotations of the suburb that a new book surveying the suburb in literature8 and richly noting Mr Wemmick’s creation ignores its lesson of individual fulfilment. The book concludes with a bleak dismissal of life as lived in the suburbs, claiming that they engender a ‘profound sense of placelessness’. ‘Surely,’ writes a reviewer,9 ‘there is scope for a more positive reading of (the suburbs)?’ Not in the minds of our English cousins, who are not praising Australian culture when they describe the country as a ‘desert surround by a suburb’.10 Nor in the mind of Australian architect and theorist, Robin Boyd, even though (as we shall see) he made significant contributions to the designing of houses in suburbia. The title of his 1961 book is The Australian Ugliness and it seems to be imbued with the same old-world disdain. Like so many Australian elites he was, as observed by cultural historian Paul Fox, torn between an allegiance to the old culture of England and the new culture of the US. While his disgust for suburban strips comes from his British heritage, his new-world allegiances brought forth his Clemson House (1959–60), which is all optimism and rethinking domestic order with, for example, a combined library/laundry room seeking to unify intellectual and menial chores.

There are, we argue, rich continuities that such polemics conceal. The poison is hidden in plain sight in the language of the Oxford Dictionary of Architecture (ODA, 1999). The definition of ‘suburb’ begins benignly, if pleading a special case, as the OED etymology shows: ‘1. Residential areas the style of which evolved from “C19” ideals associated with the Arts and Crafts and Aesthetic Movements and with the Domestic Revival and Garden Suburb … (from 1877, 1906)’, but continues: ‘… though very often a travesty, based more on commerce than aesthetics’. In its second definition, the ODA describes ‘suburb’ as a pejorative term used by modernists to promote high-rise urban developments.

Few new-world thinkers or urban theorists transcend this polemic, although some artists do, by looking hard at what is actually there, most notably Ed Ruscha in Los Angeles in the mid-1960s11 when he documented Sunset Strip (among other features of suburbia such as carparks and petrol stations) and Howard Arkley in Melbourne,12 who created a painterly language that presented the sublime innate in ordinary suburban houses in the 1980s and 1990s. Among urbanists, Mario Gandelsonas13 has a go at a positive account, using a term with a relatively new coinage, but as we shall see he is soon sucked back into the existential despair of ODA. The term he uses is ‘exurban, of or belonging to a district outside a city or town’ (1900–29) and it is followed by ‘exurb, a prosperous zone beyond suburbs’ M20 (1930–69). The latter surely describing Walpole’s Twickenham in 1750 … The relatively open fabric of exurbia excites transport planners and attracts major roads that circle cities and their suburbs. Often, like the North Circular Road (London, 1920s), these are surrounded by enterprises. Whereas in the US such roads are freeways and are called ‘Beltways’ linking nodes of concentrated urban activity, they form edge cities.14 Of these, there are dim resonances around Australian city cores as they swell. Melbourne covered 3000 square kilometres in the 1980s, 7500 square kilometres 30 years later. Exurbia is ever-receding to the horizon, suburbia filling its interstices.

Before he gets sucked back into the usual architectural polemic, Gandelsonas, who has revealed through drawing more about the impact of the automobile on urban form than anyone since Colin Rowe15 and his students exhaustively documented the figure-grounds of pre-industrial cities of Europe,16 describes suburbia and exurbia as acting to ‘transform the entire territory into a field, a metaphorical garden (across which compete) suburb/centre city, residence/workplace) …’ (p.4). Unfortun ately, by page 35, Gandelsonas is lamenting that this field is ‘neither about the architectural object nor about the plan’, thus echoing the ODA view that in suburbia ‘architectural quality (has) evaporated’. We suspect that this attitude stems from the twentieth-century history of eastern and mid-western cities in the US—‘ten cities that have suffered uniquely from the disappearance of work’ (Peter Hall, p.976). Cities that through catastrophic devaluing of their centres have lost their middle class and ‘dough-nutted’, trapping poverty ghettoes in a manner unknown elsewhere in the developed world. Maybe analysis is taking place at too high a level of abstraction. Would Gandelso...