- 246 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

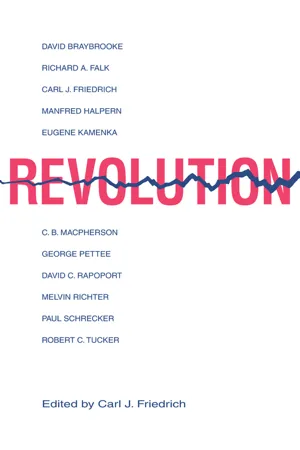

Revolution

About this book

Professor C.E. Black of Princeton University called this "a valuable contribution to our understanding of the revolutionary movements that are now a worldwide phenomenon. It includes thoughtful essays on many varieties of revolution, considered in the light both of past developments and future prospects. The twentieth century was an age of revolution. Over many areas of the world the two great ideologies of nationalism and communism spawned violent upheavals, often differing in form but aiming at the transformation of the existing order by means of coups d'etat, revolutions, and "wars of national liberation." Eleven distinguished political scientists and policy theorists offer a penetrating analysis of the theoretical and substantive aspects of revolution. Their scholarly, lucid, and well-balanced essays explore the revolutionary theories and experience of several centuries and apply them to the most crucial problem of this century. Carl J. Friedrich argues that it is the failure of government, which is at the core of the political revolution, and shows that constitutional regimes that have allowed "little revolutions" promoting gradual political and social change have been singularly free of revolutionary upheaval. Presenting the thinking of some of the best minds of the 20th century, this volume offers important guideposts for the future study of the etiology of revolutions. Here are not mere speculative and historical distillations, but new insights and conclusions regarding the origin, purpose, and impact of revolution on the world of today and tomorrow. An indispensable work for every student and scholar of comparative politics, international relations, and the history and theory of Communism, it will also be welcomed by the statesman and the educated layman who want to probe the causes of the historical upheavals of our time.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

General Theories of Revolution

1

An Introductory Note on Revolution

CARL J. FRIEDRICH

Ours is by all accounts a revolutionary age. The market place is filled with the clamor of voices proclaiming convictions which to be effective would require radical change in existing societies. While one ideology loses in appeal, another becomes more virulent in its call to action. There is no "end of ideologies" in the world, even though some of them may be more feeble in some countries.1 What then could be a more appropriate topic for philosophers of politics and law to consider? Yet, any general statement on revolution, like any general etiology of war, implies a philosophy of history.

"Revolution," as Eugen Rosenstock-Hüssy has written, "brings on the speaking of a new, unheard of language, another logic, a revaluation of all values."2 At least, it does so, when it is comprehensive or total. Antecedent to revolution, there always is resistance in any society. It may be sporadic and marginal or it may be massive and concentrated, but wherever values, interests, and beliefs conflict, some kind of resistance is apt to appear. Nullification and crime are its familiar modes of operation. Revolutions are successful rebellions; they are also rebellions on a more comprehensive scale. To resistance, rebellion, and revolution correspond in turn the continuous changes, many gradual, some traumatic and violent, which the individual person undergoes as he grows from infanthood to senility.8 And just as in the individual person, many small adjustments to a changing environment reduce the chance of traumatic experiences, so one might say that many small revolutions prevent a big one. As various detailed items of the political whole are "revolutionized" by way of a functioning political process, the tensions which would necessitate a violent and global transformation are channeled into promoting specific change. There is no better illustration of this contrast in the field of political experience than the comparison of the history of England and the continental countries in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, and the same may be said of the history of the United States. It is, in a sense, as has rightly been observed, the story of a "permanent revolution."

Trotsky once said that "revolutions are the mad inspiration of history."4 Such a statement is a poetic way of calling attention to three important features of revolutions that go far beyond the strictly political dimensions, the creative and spiritual aspirations, involving values and beliefs, the historical setting and the highly emotional fervor of the revolutionaries. It is necessary, for purposes of political analysis, to bracket out these aspects of revolutions which are presumably characteristic of the "great" revolutions of Western history, and not, or not so much, of most other revolutions of a strictly political import. Aristotle's classical analysis of "limited" revolutions in the Greek polls permits the drawing of another significant distinction; namely, that between a revolution and a coup d'état—a stroke of force at the particular rulers of an established system of government, usually executed by members of the ruling group, but not aimed at changing the system.5 (The removal of Khrushchev was an atypical coup d'état in that no manifest force was employed.) The coup d'état is frequent in unstable monocratic systems, especially dictatorships and tyrannies; it is far removed from Trotsky's mad inspirations of history; rather it is a coldly calculated maneuver in an ongoing power struggle.

Political revolution, then, may be defined as a sudden and violent overthrow of an established political order. Other revolutions, such as the industrial revolution, the scientific revolution, and the revolution of rising expectations, are quite gradual, as are the revolutions of the heavenly bodies. It may be limited or unlimited, as were the great revolutions, the English, the French, and the Russian, but its focal point is the alteration of political leadership and often that of political participation. The democratic revolutions, characteristically, have pretended to be preoccupied with securing for the people the participation in politics which a preceding authoritarian regime had denied them. Actually, they also have always been concerned with the leadership.6 Some contexts seem especially favorable to revolutionary upheavals, e.g., Latin America and ancient Greece, while others, notably the constitutional regimes of Western Europe, particularly Great Britain and the Scandinavian kingdoms as well as Switzerland and the Netherlands, seem to have been singularly free of such sudden and violent alterations, as have been the United States and the British Dominions. The reason is to be seen primarily in the operation of constitutional mechanisms that allow and even promote social and political change, as contrasted with the Aristotelian tradition and its preoccupation with stability. Whether such devices as constitutional amendment, judicial interpretation and skillful manipulation could ward off the pressures which a "mad inspiration of history" might generate is an open question; there is at least a possibility that this might be the case. But if the constitutional morality—that is to say the belief in constitutionalism as such—became corroded, as it did in ancient Rome, presumably no constitutional device would continue to function effectively.

A number of writers, notably Crane Brinton and George Pettee, undertook some years ago to distill a kind of phenomenology of the revolutionary process.7 They concentrated on the unlimited great revolutions in which they perceived a succession of stages which do not necessarily appear in the limited revolution, such as the American one. There is, however, one aspect which seems to be common to all revolutions and that is the re-establishment of more effective government; for it is the failure of government which is at the core of the political revolution. In the American Revolution, for example, we find neither the victory of the extremists, nor the terror, nor the Thermidor, nor yet the "tyrant" dictator who re-establishes a measure of order—all of these stages of the unlimited revolution. But a strong and more effective government did emerge from the Revolution. The absence of the other phases presumably is linked to relative weakness of the ideological factor.8

When we say that the problem of an effective government is at the core of a political revolution we have raised the problem of the causes of revolutions. The theory of revolutions since Aristotle has been focused on such an etiology (as contrasted with recent comparative analysis of the process). Aristotle thought, it will be remembered, that disputes about equality and justice and about property were the main grounds leading to revolutionary upheavals and the overturn of governments. These disputes he analyzed in terms of the feelings and motives of the revolutionaries and of the situations which give rise to them.9 Modern writers have followed this approach, but they have substituted other "basic values" such as freedom, security, and the like for equality and justice. But no particularly useful purpose is served listing such vague general terms as causes or grounds for revolutionary sentiment; they will of course always be invoked. Being very general values motivating all politics, they will necessarily enter into any revolutionary enterprise, as real motivations, as ideological slogans, and as rationalizations. This statement is not meant to argue for a "value-free" analysis of revolutionary process; far from it. Rather, it is meant to urge that these general values be specified in the concrete situation, while the causal relationship should be stated even more abstractly in terms of conflict over values, beliefs, and interests. Only a cumulation of stresses and strains, of frustrations and deprivations will, if they accumulate, build up into a revolutionary situation.10

Because European revolutions in the seventeenth to nineteenth centuries were directed toward the establishment of constitutional regimes, there has been a tendency for man to assume that such must be the natural thrust of a revolution. But in point of fact, many other revolutions, including quite a few in the twentieth century, were directed toward nothing but the alteration of the political order, not infrequently in the direction of a concentration of power rather than its constitutional division. Realistically considered, a revolution carried forward by a group which wants to establish a constitutional order (a constituent group, that is) is a different process from a revolution made by proponents of a concentration of power, more particularly totally unrestrained power.

More often than not, constitutional revolutions are limited. Such were the negative revolutions of the period following the Second World War in Europe;11 such have been some of the revolutions in the formerly colonial world. These revolutions were and are preoccupied with the problem of how to organize an effective government of some sort. But when the government so established did not prove effective—as happened, for example, in France, in the Sudan, and in Pakistan—such a revolution was quickly followed by another which was not (or need not be, as in France) constitutional, but rather aimed at the establishment of a military dictatorship. A well-drawn constitution may anticipate the occurrence of such a limited revolution by so constructing the amending process that developing pressures for change can find expression in suitable alterations of the existing order, even to the point of a complete revamping, as happened in Switzerland in 1874. But this procedure, too, is aimed at providing more effective government. In other words, here too the objective is the remaking of the political order.

One more word about the negative revolutions just mentioned. They have been characteristic of recent constellations in both Western and non-Western countries. In these cases, we find no positive enthusiasm for constitutionalism, let alone a new order. These revolutions, rather, occur as the result of negating, of rejecting a past political order, because of its failure, its "immoral" leadership, and other defects. In France, Italy, and Germany, as well as in Japan, such negative revolutions occurred and produced new constitutions which do not possess popular support to any significant extent. Nor do the constitutions which result from them arouse much loyalty and understanding, affection or enthusiasm.12 In Germany, Italy, and Japan the established regimes continue to exist largely because of an absence of viable alternatives and a widespread resigned skepticism regarding all politics. Frenchmen before the collapse of the Fourth Republic almost to a man agreed in condemning its constitution, and their view of the Fifth, General de Gaulle apart, is not much more favorable. In former colonial territories, constitutions have been fashioned on alien models and without any supporting beliefs.13 Some residual political enthusiasm is expended upon unification movements—Pan-Arabism, Pan-Africanism, and a United Europe—but the revolutionary determination which the building of such novel structures requires is limited to quite restricted circles.

In conclusion, I would say that the phenomena of political revolution and resistance are endemic, in any political order, and they are closely related to each other. To avoid them or reduce their menace to a minimum, effective change has to be organized to make possible recurrent adaptations of the institutions and processes of a political order to evolving values, interests, and beliefs by gradual transformation of such an order. Otherwise violence will take over, sporadically as resistance at first, globally and all-engulfing as revolution in the sequel. Political orders resemble forests and families. They contain the potentiality of self-renewal, but this potentiality does not exclude the chance of failure and ultimate extinction. Revolution, when successful, signalizes such passing of a political order. It is not in itself a good, as contemporary political romantics are inclined to feel, but it is better than the death of the society which such an order is intended to serve.

1 Raymond Aron and Daniel Bell among others have, on the basis of the weakening of Marxist and generally Leftist ideologies in the West, advanced such claims.

2 Eugen Rosenstock-Hüssy, Die Europaeischen Revolutionen (1931, 1951); English version (rev.), Out of Revolution (1938).

3 The brief observations which follow are more fully developed in my Man and His Government (1963), ch. 34; resistance is there treated at some length.

4 Leon Trotsky, My Life (1930), p. 320.

5 Curzio Malaparte, Coup d'État: The Technique of Revolution, S, Saunders, tr. (1932); Vincenzo Gueli, "Colpo di Stato," Enciclopedia dal Diritto (1960); D. J. Goodspeed, The Conspirators: A Study of the Coup d'État (1962).

6 The theory of modern parties (and movements tend to be like them) has brought this out clearly; cf. the definition of party, given op. cit. fn. 3, p. 508 which stresses (as have others) that a party "seeks to have its leaders become rulers. . ." Cf. also Max Weber, Wirtschaft and Gesellschaft (1922), part I, par. 18, and part III, ch. 4.

7 Crane Brinton, The Anatomy of Revolution (1938); George S. Pettee, The Process of Revolution (1938); R. B. Merriman, Six Contemporaneous Revolutions, 1640—1660 (1938); cf. also the much earlier work by P, Sorokin, The Sociology of Revolutions (1925). Later, Harold Laski, Reflections on the Revolution of Our Time (1943), and Sigmund Neumann, Permanent Revolution (1962), undertook to relate the problem to the rise of dictatorship and totalitarianism. Cf. also more recently Hannah Arendt, On Revolution (1962).

8 Ideology is here used in its specific political and functional sense; for this cf. my op. cit., ch. 4.

9 Aristotle, Politics, Bk. V. Although usually translated as "causes" of revolutions, aitiai are not merely efficient causes (the prevalent meaning of "cause" today), but grounds, nor is stasis, strictly speaking, merely a revolution, but any kind of overturn. Aristotle's discussion at 1301b would apply to a modern election. He puts the problem in this very broad context by asking: (1) What is the feeling? (2) What are the motives of those who make overturns? (3) Whence arise political disturbances and quarrels? (1302a).

10 Pettee, op. cit., passim.

11 Gf. my chapter, "The Political Theory of the New Democratic Constitutions," in Constitutions and Constitutional Trends Since World War II, Arnold J. Zurcher, ed. (1951, 1955).

12 John D. Montgomery, Forced to ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title

- Copyright

- Preface

- Contents

- CONTRIBUTORS

- GENERAL THEORIES OF REVOLUTION

- REVOLUTION, IDEOLOGY, AND INTERNATIONAL ORDER

- MARXIST REVOLUTION: ITS MORAL DIMENSION

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Revolution by Carl Friedrich in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politics & International Relations & Political Freedom. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.