![]()

Introduction: Countervailing forces and the industrial ethic

1.1 Introduction

This is a book about industrial-scale mining and the approach by that sector in responding to a rapidly changing landscape of stakeholder expectations, regulation and everyday concepts of social responsibility. The authors engage with a set of contemporary questions reflecting concerns from across the stakeholder spectrum: What are the industry’s social responsibilities? How are these responsibilities defined and how are they articulated to the industry? What does the mining sector make of these responsibilities? What effect do these expectations have on the day-to-day operations of mining companies, and the activities of communities that host them? What happens when these expectations cannot be met by the industry?

In exploring these questions, it is important to understand the historical landscape in which stakeholder expectations are being formed. As scholars and practitioners our focus is how a core group of stakeholders come together to negotiate their expectations and interests: mining companies, international financial institutions, nation states, non-government organisations, resource consumers, and local host communities. There are few instances in which these groups are able to interact directly all at the same time; and while there are emerging electronic platforms that enable different stakeholders to share information, physical distance continues to determine the format and character of stakeholder interactions. Resource consumers, for instance, will rarely observe first-hand the local-level activities of a mining operation, or the way mining companies, government regulators and host communities engage over the distribution of impacts and benefits. The point being made is that expectations about the social responsibilities of mining companies and other actors are often shaped via related historical events or through the influence of popular discourse, rather than through direct personal experience with the sector.

Over the previous three decades, an international political economy of globalisation has concentrated almost exclusively on multinational corporations as the drivers of change. In the popular imagination, multinational corporations are depicted as characteristically and irredeemably flawed actors: exploitative, greedy, profit and not people orientated. The global financial crisis between 2007 and 2009 consolidated the view that large multinational corporations were operating without regard for the public good, and that the mechanisms employed by nation states for regulating private greed had failed.

Following the global financial crisis, the immediate emphasis was on financial institutions. In the decade since, a similar set of questions have formed around other large multinational corporations. For example, what formal obligations do multinational corporations have in specific jurisdictions? What constitutes a global headquarters? In which country should a multinational company pay its taxes?

Environmental disasters involving energy and resource development companies have likewise left an imprint on the popular consciousness. For the most part, these events leave an impression that is overwhelmingly negative, and casts resource development and the environment as a set of opposing pairs. The way that large corporations handle environmental disasters has not helped to ease public concerns. If anything, the response by resource developers in the aftermath of disaster events has confirmed the popular view that the drivers of resource extraction and the principles of environmental sustainability are firmly incompatible.

In April of 2010, an explosion on the drilling platform of British Petroleum’s (BP) Deepwater Horizon project resulted in millions of barrels of oil being spilled into the Gulf of Mexico. The event received widespread coverage in print and online media and has been declared the worst oil spill in the history of the United States of America (USA). In early April 2016, a USA court approved a settlement with BP for natural resource injuries stemming from the oil spill. This settlement marks the conclusion of the largest natural resource damage assessment ever undertaken. Under the settlement, BP is required to pay up to US$8.8 billion to address natural resources injuries.

The Fukushima nuclear disaster in March 2011 received a similarly high level of media attention. Almost one year following the BP oil spill, an earthquake registering a magnitude of nine occurred 130 km offshore in the Pacific Ocean to the east of Sendai city in Japan. Approximately one hour later, a 15 metre tsunami inundated the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear reactors, disabling the power supply and cooling systems of three reactors, causing a nuclear incident in which large exclusion zones were enforced. At least 1,500 people died as a result of radioactive exposure and the trauma of displacement. An intensive clean-up effort was organized by government authorities and the operator, Tokyo Electric Power Company, with further efforts expected to continue for at least another thirty years.

The mining industry has itself contributed numerous industrial disasters. One of most famous is the environmental catastrophe of the Ok Tedi copper and gold mine in the Western Province of Papua New Guinea (PNG). Professor Stuart Kirsch (2014), a well-known anthropologist and critic of the mining industry, has described the Ok Tedi case as a “slow-motion environmental disaster” (p.133). As a result of being unable to construct a workable tailings storage facility, the Government of PNG allowed the mine, then majority owned by Australian mining giant, BHP, to dump tens of thousands of tonnes of waste daily in the local river system. Over a period of 30 years, the Fly River was progressively contaminated with the sludge of mine tailings. The thick waste from the mine eventually clogged the local river system, and affected the rural livelihoods of hundreds of villages located along the entire length of one of PNG’s major river systems.

The environmental and social distress caused by the Ok Tedi mine is not an isolated example. Mine disasters do not only occur in developing countries where the regulatory controls may be weak or ineffective; they can also surface in advanced, developed nations where regulatory codes and standards are more strictly enforced. In 2014, a breach of the mine’s tailings dam at the Mount Polley Mine devastated the Cariboo region in the Canadian province of British Colombia. Following the failing of the tailings facility, billions of tonnes of waste were released into the local river system. Water tests confirmed elevated levels of heavy metals, and signs of significant impacts to the local ecosystem. An investigative report published in 2015 concluded that the dam had been operating beyond capacity for at least four years. In August 2016, it was announced that the indigenous nation of Tsilhqot’in had filed a claim in British Columbia’s supreme court and was actively seeking compensation from Imperial Metals for the damage caused by the dam failure. Esdilagh First Nation chief Bernie Mack claimed in a press statement that:

Not only were our people directly impacted by the uncertainty of the safety of our fish and wildlife for consumption, but the economic development of our nation was also affected as our commercial fishery was effectively cancelled.

We are filing this (civil claim) notice to hold the company, its engineers and the province accountable and to ensure our people receive compensation for the failure of the province of British Columbia and Imperial Metals and the huge impact this disaster has had on our food and economies. We are disappointed the province has given the company a free pass. This is not an example of responsible and sustainable mining. (Lamb-Yorski, 2016)

A more recent case in point is the collapse of the tailings dam at the Samarco iron ore mine in the Brazilian state of Minas Gerias. The Samarco mine is a joint venture between BHP Billiton and Vale, two of the world’s largest mining companies. Both companies are members of the International Council of Mining and Metals (ICMM), the industry’s peak body, and have publicly committed to promulgating the principles of “sustainable development”. The catastrophic collapse, which commenced on the 5 November 2015, resulted in the loss of at least 19 lives, and the displacement of hundreds of homes and businesses as mine waste spread into the Doce River and out to the Atlantic Ocean. The tailings dam had been in place since 1977 and, up until the point at which it collapsed, was not considered to be a significant risk. In late October 2016, it was reported that Brazil’s Federal Prosecutors Office had filed claims of qualified homicide (manslaughter) against 21 individuals, eight from BHP, and 13 from Vale and the Samarco joint venture company itself (Fitzgerald, 2016). The claims need to be approved by a judge before the case proceeds to court, but regardless of whether it proceeds, it is obvious that the social, legal and financial fall-out of the dam disaster will continue for decades. During a press conference, federal prosecutor Eduardo Santos de Oliveira stated that victims of the dam break:

… were killed by the violent passage of the tailings mud, they had their bodies thrown against other objects, such as pieces of wood, they had their bodies mutilated and … dispersed across an area of 110km.

The federal prosecutor added that “The motivation of the homicides was the excessive greed of the companies—Samarco, here charged, as well as its shareholders—in the name of profit” (Fitzgerald, 2016).

On this reading, one could easily form the view that mining companies are operating in a world bereft of regulation. This is not the case. The number of national and international safeguards and standards that promote responsible resource development has in fact increased exponentially over the past 15 years. From a general absence of international instruments at the turn of the twenty-first century, there is now a vast array of schemes, frameworks and mechanisms that are applied to the sector. In mining, the World Bank’s private sector lending arm, the International Finance Corporation (IFC) has been the most influential. The IFC’s pro-business, people-sensitive Environmental and Social Performance Standards have become the performance benchmark to which much of the industry subscribes.

The full set of international safeguards and standards represent a major effort to strengthen global regulatory mechanisms around the sector. While mining companies largely consider such schemes to be an inconvenience, even a burden, these mechanisms reflect an evolving set of stakeholder expectations and the power that particular stakeholders have been able to wield in a relatively short period of time. From this international system of “soft regulation”, it is clear that stakeholders expect mining companies to factor in social, cultural, environmental and spiritual values of host communities, in addition to the usual considerations around profit and production.

The industry response to this system of “soft regulation” is as varied as the standards themselves. Some companies have responded by engaging these new obligations, and attempting to embed them in their corporate policy frameworks, employing people with expertise outside of the core business of mining and minerals processing, and re-aligning their corporate goals to accommodate these evolving norms and expectations. Others pay lip service while subverting or otherwise ignoring these expectations in material and substantive terms.

1.2 Our approach: Extractive relations and countervailing power

The title of this book, Extractive Relations: Countervailing Power and the Global Mining Industry, requires some explanation. Our use of the term “extractive relations” refers to the fact that mining operations extract resources from the physical environment. What is less obvious is that this same extractive approach is applied to the social environments that host mining developments. From our perspective, the term usefully covers a range of activities and entanglements in which mining companies are the central actor. These include the way mining companies engage and recognize landowner groups and their interests in the development process, configure their social investments over the mine life cycle, interpret the interests that drive and later sustain negotiations and agreements with local communities, and the management of impacts and legacy issues.

While mining companies are the lead actors in extracting minerals and producing metals, their relationship with external parties can be mutually extractive. That is to say, mining creates opportunities for different individuals and organisations to extract a share or a benefit from the mining business. In some instances, these extractions are made based on a right that a local party is entitled to. In other instances, external parties are more opportunistic and can include rent-seeking demands when local communities believe they are entitled to a greater share of the mining wealth than they would otherwise receive. There are many forms of extractive relations that occur in the context of resource development. This extractive approach is therefore not the exclusive domain of mining companies, but rather a dynamic norm that surfaces around resource development projects.

The case for approaching mining as a dynamic set of extractive relations is most apparent, and most easily recognized by observers, when considering the relationship with external stakeholders and the environment. Commentators have directed much of their attention to this form of extractive relationship, and with good reason. The advent of a foreign mining interest in a typically remote location extracting resources from an otherwise pristine environment, naturally raises a certain kind of intellectual curiosity. We share this curiosity. Unlike other commentators, however, our curiosity extends into the organisational structure of mining companies. Our engagement with this industry suggests that mining businesses also construct extractive relations within their own company structures, and that these relationships are used to meet specific goals and objectives. In this book, we explore a range of issue areas that represent this extractive approach.

1.3 A conceptual schema for examining countervailing force and power

Like many critics of the global extractives industry we too have taken an interest in the problems brought about by the excessive power of large corporations. A key issue is the problem of excessive power and its corrosive effect on the ability of near and distant actors to limit, expose or seek redress for harms created by the industry.

In responding to this concern, we have developed a conceptual schema based on the work of two notably different scholars: Samuel Coleridge, a British political philosopher and prominent literary figure, and John Kenneth Galbraith, a highly influential American institutional political economist. The schema consists of three primary components: (i) countervailing forces, (ii) the industrial ethic and (iii) countervailing power. The first two concepts in this schema are adapted from Coleridge, the third concept is taken directly from Galbraith. Before describing each of the components individually, it is necessary to explain the structure of the schema itself.

Our sequencing of the schema is driven by our observations on the structure and use of power within and surrounding the mining industry. Coleridge’s ideas on countervailing forces precedes Galbraith’s theory by more than a century and were applied in an era where markets were in the process of industrialising. This was an era of history in which many of the social protections provided under the feudal order were being tested by a new world order based on a capitalist logic and a system of provisioning built around mechanisation and mass production. These changes brought with them efforts to privatize common pool resources, and the mass eviction of rural people from land that they had held customary rights to for centuries. Emerging industrial centres, built on manufacturing, were swollen with generations of rural people still reeling from their dispossession. What Coleridge describes as “countervailing forces” are a set of mechanisms and principles he believed could allow the new economy to grow in a just and reasonable manner.

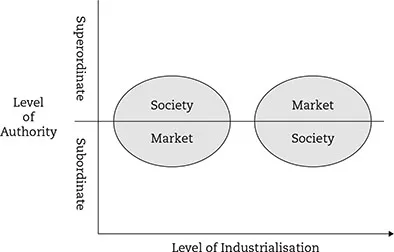

An important point to note is that in Coleridge’s time the process of industrialisation was not complete. Market norms were not yet established as “natural”, and social forms of regulation continued to hold legitimacy in custom and in law. According to the political economist Karl Polanyi (1944), the working of markets in this historical era were mostly “embedded in social relations” which meant that the countervailing forces espoused by Coleridge were largely consistent with the social and customary norms of his day. In this arrangement, the substance of Coleridge’s countervailing forces were in many respects normalized and accepted; it was the force of industrialisation and the emerging power of the commercial spirit that was at odds with popular and legal expectations. The process that Polanyi describes as “disembeddedness” is one in which markets, and market interests are separated from social forms of regulation and, in effect, become self-regulating (see Figure 1.1 below). When Coleridge decried the perils of a rampant commercial spirit, he was still hopeful that the forces of an embedded form of social regulation would prevail and eventually come forth to soften its impact.

FIGURE 1.1 From the social regulation to the self-regulation of commercial interests

In this book, we argue that the industrial scale and global reach of international mining corporations creates new dimensions when compared to the types of self-interest observed by Coleridge in the early nineteenth century. For Coleridge, commercial self-interest posed a risk to the viability of countervailing forces; our observations hold closely to Coleridge’s in this regard. We are concerned that even under circumstances where corporations voluntarily subscribe to key international frameworks, for instance business and human rights, commercial self-interest can all too easily dominate, and the countervailing force, for example the Voluntary Principles on Security and Human Rights (2000), is put to the side. In other instances, the countervailing force of national legislation must be able to withstand the power and influence of corporate interest, or indeed the nation’s own interest for revenue generated by the industry. We refer to this contemporary form of commercial self-interest as the “industrial ethic”.

The third component of our schema is countervailing power. Galbraith’s term, while linguistically similar to the notion advanced by Coleridge, is markedly different in its meaning. The key point—and the primary justification for its inclusion in our schema—is that countervailing power is the reaction to excessive power and influence by corporations. Galbraith’s concept contains importance nuances that make it useful for examining the exercise of power in mining, and the responses gene...