- 328 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Alois Riegl (1858-1905) was one of the founding fathers of modern formalist criticism. As a member of the Vienna School of Art Historians, he shared their range of interests in the decorative arts, art in transition, conservation and monuments. This collection of critical essays examines various facets of Riegl's work and opens with a new translation of Hans Sedlmayr's famous, and notorious,Die Quintessenze der Lehren Riegls. Included is Julius von Schlosser's assessment of Riegl's contribution to the Vienna School of Art Historians as well as essays by a team of international scholars. This book offers a re-engagement with the ideas of one of the most important and neglected art historians of the 20th century.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Topic

ArtSubtopic

History of Arti’ve got you under my skin:

rembrandt, riegl, and the will of art history*

rembrandt, riegl, and the will of art history*

Sweet is the lore which nature brings;

Our meddling intellect mis-shapes the beauteous forms of things;

—We murder to dissect.

Enough of science and art; close up these barren leaves;

Come forth, and bring with you a heart that watches and receives.

—Wordsworth

introduction: anatomy lessons

ANATOMY IS DESTINY, FREUD ONCE proclaimed.1 This essay addresses the fate of anatomy in Rembrandt’s Anatomy Lesson of Dr. Tulp and Anatomy Lesson of Dr. Deijman as an occasion to reconsider Aloïs Riegl’s 1902 study of the Dutch group portrait in relation to subsequent art historical commentary. Riegl’s study is still relevant because his explanations of the formal strategies of Dutch painting and Rembrandt’s art remain unsurpassed, and his broader argument anticipates crucial methodological debates. The changing interpretations of Rembrandt’s anatomy lessons can serve to elucidate the stakes of art history and provide an opportunity to combine the perspectives of Riegl and later commentators to produce new readings.

The current reception of Riegl is ambivalent. What one commentator calls “the modern Riegl-cult,” punning on the title of one of his essays, is limited to scholars of modern art and based on his influence as a formalist, whereas scholars of earlier art generally reject the Hegelian framework of his argument.2 Most explicit discussions of Riegl situate him in his art historiographical context in relation to intellectual predecessors and contemporaries.3 This situation is paradoxical. How can the value of Riegl’s approach be assessed without examining his close readings of particular works in relation to other interpretations?

In my view, Riegl’s attention to the formal strategies of particular works constitutes the essence of his theoretical and historical argument. Through a system of opposed terms, he articulates the Kunstwollen or “will of art” evident in specific periods, traditions, genres, artists, or works as a manifestation of culture and thought; in his own words, the central issue “does not reside in the what at all, but in the how of representation,” an old-fashioned version of what is now called reading on the level of the “performative.”4 Instead of attempting to establish the ostensible message of a painting for its historical audience, Riegl addresses changing approaches to representation as ways of seeing the world, offering an epistemology of vision, and anticipating a semiotic view of art.5 In contrast to Hegel, Riegl’s teleology is grounded in close reading of the works themselves, whereas his emphasis on the role of the beholder underscores how art transcends its historical context to address us, and thereby opens the possibility of future interpretations. In short, Riegl performs an anatomy lesson on art, “lifting the skin” to show us how art operates, and how we are involved in a living process, rather than, in Wordsworth’s phrase, “murdering to dissect.” As Riegl puts it, “this art historical approach, which endeavors to look underneath the surface appearance of things, and thereby uncovers essentially new areas, must of necessity first create its own dialectical terminology, which will not immediately be comprehensible to every reader.”6

Another potential difficulty with Riegl’s texts is their length. Like his other major works, Riegl’s study of the Dutch group portrait is both exhaustive in scope and exhausting in exposition, which would help explain the delay in its translation, and the tendency to publish short excerpts.7 Here I propose to narrow the focus even further to Riegl’s readings of Rembrandt’s anatomy lessons, and to open up an analysis of his argument in relation to later commentary, specifically iconographic studies of Rembrandt’s Tulp, Erwin Panofsky’s method, and recent texts on Rembrandt by Svetlana Alpers and Mieke Bal, as representative of the old art history in practice, and theory; the so-called new art history; and art history or cultural studies in the interdisciplinary present, respectively. Each of these perspectives involves concerns relevant to Riegl’s argument, and in each case the rigor of his analysis can serve as a corrective and a means to reconcile conflicts, by grounding all these commentaries in the performative level or “how” of the art work.

In his own essay titled “A New Art History,” Riegl compares the evolution of his discipline to the building of St. Peter’s in Rome. The work of Winckelmann and his successors correspond to Bramante’s columns, which had to be “reinforced” by positivistic research in the nineteenth-century, before the equivalent of Michelangelo and Della Porta’s crowning cupola could be constructed in the form of a theoretical model encompassing all art history, to be supplied by Riegl himself.8 Riegl’s present relation to the discipline is more accurately characterized as a (neglected) foundation, yet instead of situating him within an art historiographical canon or basilica, or to use anatomical terminology, performing a postmortem on his text, this essay will stage a live confrontation and dialogue between Riegl and later commentators. To adapt Riegl’s neologism, not only art but art history has a will of its own, in which his insights can still play a vital role.

The specific topic of Rembrandt’s anatomy lessons will allow for an elaboration of Riegl’s argument in terms of an indexical relation between the paintings and the bodily beholder: the body, mind, and eye of the beholder in the most literal sense.9 Rembrandt’s paintings manifest Riegl’s concepts of attention, opticality, and coordination—far more self-consciously and brilliantly than Riegl recognized—in their performative emphasis on sight and on the role of the beholder, who is situated as a participant in a living process in relation to both the dissected corpses and Rembrandt’s compositions, a dynamic succinctly captured in Cole Porter’s lyric, “I’ve got you under my skin.” A transition is also evident from the central conceit of the hand in Rembrandt’s earlier anatomy lesson to the brain in the later example, and from his relatively narrative earlier work to the emphatically optical approach of his late works, which manifest his increasing reflection on the nature of representation, or the relation of sight to thought. Rembrandt’s paintings perform anatomy lessons on themselves, and thereby anticipate crucial philosophical and psychoanalytic concepts, which can be related to Riegl’s argument in turn. Riegl helps us to read Rembrandt, and Rembrandt helps us to read Riegl, other commentators, and ultimately ourselves. This double-bind is a tribute to the power of Riegl’s analysis, and its continuing relevance and productivity for art history today.

i. riegl on rembrandt

Riegl’s group portrait study is predicated on an opposition between the Dutch and the Latin or Italian (Romanisch) will of art. The figures in Italian history paintings express their will through physical action, subordinated to one another along diagonals in a self-contained narrative or “internal unity,” and are rendered in haptic or palpably three-dimensional terms through linear contour and volumetric form on the picture plane. By contrast, the figures in Dutch group portraits express psychological “attention” through their calm poses and expressions, coordinated vertically beside one another and through their out-turned gazes with the beholder to establish an “external unity,” and are rendered through the optical play of light and shadow in space approximating the physical perception of the beholder and the artist. The latter principle also applies in other categories of Dutch painting such as genre scenes, landscape, and still life, which like group portraits embody the legacy of Protestant iconoclasm, the democratic character of Dutch society, and the celebration of native culture accompanying Holland’s political autonomy. More generally, Riegl claims that Dutch art inaugurates a new aesthetic paradigm: “the Dutch were the first to realize that objects could be captured for the subject insofar as they entered into the subject’s consciousness as mental images… attention is essentially mental image [Vorstellung; also representation, idea].”10 The form or manner of rendering and content or themes of Dutch paintings represent perception and mental image.

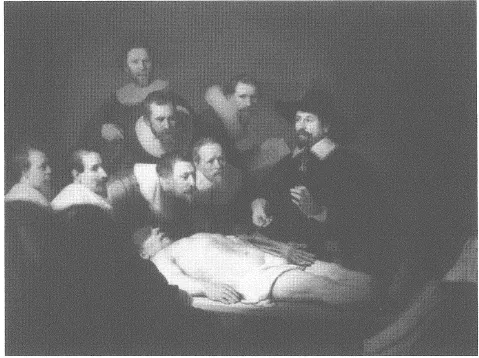

Riegl’s dichotomy is not absolute, since Dutch painters progressively introduced a narrative dimension during the course of the seventeenth century. Near the end of his study Riegl turns to Rembrandt, the greatest Dutch artist, who chose to become a history painter. When he took up his native genre of group portraiture, he accordingly introduced an unprecedented internal unity, yet did so in order to heighten the external unity and coordination. His first group portrait, The Anatomy Lesson of Dr. Tulp of 1632, depicts Dr. Tulp subordinating several surgeons through his lesson, while a single surgeon at the back looks directly out at us (Fig. 1). Yet Rembrandt also balances his use of haptic overlap, foreshortening, and the pyramidal arrangement of the group on the plane through chiaroscuro, which eliminates outline and tactile form and integrates the figures within the surrounding space in relation to the beholder. The composition incorporates physical movement, the expression of will, and diagonals, yet these serve the purpose of forging coordination between the figures and with the beholder in turn:

In order to come to a clear understanding of the picture’s embodiment of attention through its soft nuances of compassion, it is necessary for us to undertake a formal psychological investigation of the facial expressions of the individual heads. This kind of investigation, which is of course completed only unconsciously by the naive beholder of the picture (as opposed to the art historian), demands such an absorption of the beholding subject’s consciousness in the internal psychological connections of the scene that the latter seems to be transformed from an external, objective event into an inner experience of the beholder.11

Figure 1 Rembrandt, The Anatomy Lesson of Dr. Tulp, 1632, Mauritshuis, The Hague. (Photo credit: The Mauritshuis.)

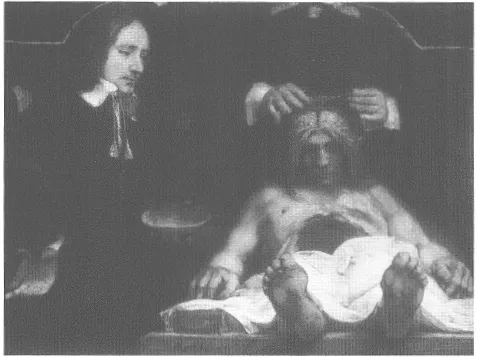

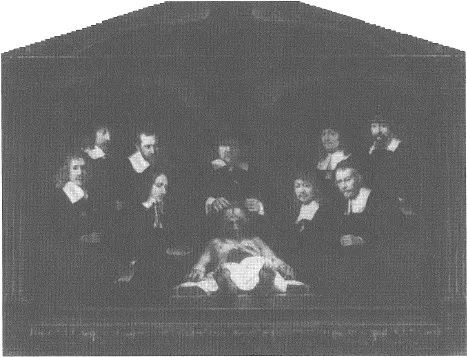

Rembrandt’s third group portrait, The Anatomy Lesson of Dr. Deijman of 1656, survives only as a small fragment, together with a sketch of the composition as a whole (Figs. 2 and 3.). Dr. Deijman at the center subordinates the other surgeons, yet the latter are coordinated through the expression of pure attention. The external unity is now established by the corpse extending feet-first toward us, and through the symmetry of the composition as a whole, which is experienced as if arranged for the sake of the beholder. This relation is further established by Rembrandt’s late broad painting style, which eliminates linear contour and volumetric form to integrate the figures and setting in spatial depth to constitute an “optical plane.” He thereby reconciled himself to his native tradition at the end of his career, when coordination was no longer a priority for his contemporaries: “the recognition that was denied to him at that time was first bestowed upon him by art historical research and observation at the end of the nineteenth century.”12

Figure 2 Rembrandt, Anatomy Lesson of Dr. Deijman, 1656, Amsterdams Historisch Museum, Amsterdam. (Photo credit: Historische Museum.)

Figure 3 Rembrandt, sketch for Anatomy Lesson of Dr. Deijman, 1656, Amsterdams Historisch Museum, Amsterdam. (Photo credit: Historisch Museum.)

ii. the old art history, practice: riegl and the iconographers

In the first extensive examination of Rembrandt’s Tulp after Riegl, William Heckscher rejects what he sees as anachronistic emphasis on Rembrandt’s genius and purely aesthetic considerations, and turns instead to the patrons and iconographic motifs. Heckscher reconstructs Rembrandt’s original composition without the surgeon at the far left or the surgeon at the back, “who forms the apex of a Rigelian [sic] pyramid and who has nothing to recommend him in dress, pose, technique, or iconographic raison d’existence.”13 Subsequent analysis of the painting has revealed that only the figure at the far left was a later addition; the haziness of the figure at the back is a deliberate use of atmospheric or optical perspective to indicate his position in depth.14 Heckscher also observes that anatomical dissections in this period always began with the stomach, not the arm as in Rembrandt’s painting. He believes this deviation was inspired by the great Renaissance anatomist Andreas Vesalius, who was the first to dissect the human hand, punned on the word for surgeon, cheirourgos, derived from the Greek for “manual labor,” and had himself depicted demonstrating the tendons of a dissected hand in his portrait frontispiece for his De Humani Corporis Fabrica. As Vesalius Redivivus, Dr. Tulp holds up the tendons of the corpse’s arm with forceps in his right hand and makes a rhetorical speaking gesture with his left hand, illustrating nimbleness and eloquence, respectively, the cardinal virtues of the anatomist.15

In a subsequent book, The Paradox of Rembrandt’s “Anatomy of Dr. Tulp,” William Schupbach rejects Heckscher’s explanation and proposes, along lines suggested by earlier commentators, that Tulp’s left hand demonstrates the operation of the exposed tendons of the corpse’s hand, which he holds with the forceps in his right hand to make the corpse echo his gesture.16 Schupbach identifies Tulp’s left hand as an illustration of the divinity of man, his gaze as the rapture of divine enlightenment, and his lips as saying: “Behold the wisdom of the almighty God which passeth all understanding.” Conversely, the surgeon at the back points to the corpse as an emblem of vanitas or the transience of human life, hence the paradox of Rembrandt’s picture.17

Although he acknowledges the crucial demonstrative function of Tulp’s left hand, Schupbach still has this accompany spoken words and theological abstractions. Yet the hand motif illustrates, precisely to the contrary, the priority of sight over speech as a vehicle for concrete human understanding. In the title-page of his Fabrica, Vesalius was depicted making the same speaking gesture at an anatomy lesson. Rembrandt deliberately transforms the gesture into a visual demonstration in ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- contents

- Introduction to the Series

- Introduction – Aloïs Riegl: History’s Deposition

- The Quintessence of Riegl’s Thought

- Aloïs Riegl

- Reading Riegl’s Kunst-Industrie

- Space, Grace, and Stylistic Conformity: Späträmische Kunstindustrie, and Architecture

- Problems of Style: Riegl’s Problematic Foundations

- Aloïs Riegl: Volkskunst, Hausfleiss, und Hausindustrie

- The Vital Skin: Riegl, The Maori, and Loos

- The Reception and First Criticism of Aloïs Riegl in the Czech Protection of Historical Monuments

- Riegl and the Family Portrait, or How to Deal with a Genre or Group of Art

- I’ve Got You Under My Skin: Rembrandt, Riegl, and the Will of Art History

- Subjectivity and Modernism: Riegl and the Rediscovery of the Baroque

- Works That Have Lasted… Walter Benjamin Reading Aloïs Riegl

- Commentary

- Contributors

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Framing Formalism by Richard Woodfield in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Art & History of Art. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.