![]()

1

Toward a Geography and History of the Public Realm

Humans invented the city some five to ten thousand years ago,1 but up until the past two and a half centuries, most especially until the past century, only a miniscule proportion of the human population had ever had the experience of urban living. While some preindustrial cities may, even by modern standards, have been quite large in population, the majority were modestly sized.2 Morever, at any given historical moment, extant cities were few in number, with most of the earth's population living out their lives in less complex physical and social environments: small bands, nomadic tribes, villages. As late as 1800 "only 3% of the human population lived in cities of 100,000 or more" (Sadalla and Stea 1978:140). In marked contrast:

The number of metropolises with over a million inhabitants has tripled during the past 35 years. . . . U.N. projections indicate that there will be 511 metropolises exceeding a million inhabitants by 2010. Thereafter, more than 40 such metropolises will be added every five years, so that in the year 2025, there will be 639 metropolises exceeding one million residents. Before the children born in 1985 become adults, half of the world's population will be urban, and half of this half will be located in metropolises with over a million inhabitants.

(Dogan and Kasarda 1988:13, emphasis added.)

In other words, in a phenomenally brief period of time, humans have managed to transform themselves from a predominantly rural people to a significantly urban people.

Given the lightening-fast character of this transformation, perhaps we should not be surprised at how little they know about their new environment, how negatively some of them view it (what a source of dis-ease it is to them), or even how resistant some of them are to granting it more than temporary status. But the brevity of the human encounter with the city may not tell the whole story. The antiurban feelings themselves, combined with the belief that the city is an "unnatural" and therefore impermanent human habitat, may contribute to the lack of knowledge. In the words of Jane Jacobs's mildly sarcastic query, "How could anything so bad be worth the attempt to understand it?" (1961:21). And such willful ignorance may, in turn, help to create urban conditions that generate and/or reinforce anticily sentiments.3 In sum, among the many other "pickles" the human species has gotten itself into of late, add this one: a near majority of us are now or will soon be living in a social-psychological environment that we do not understand, that many of us despise, and that, because we act toward and on it out of ignorance and prejudice, we may be making unlivable.4

This book is written in the naively optimistic belief that having gotten ourselves into this particular pickle, we can get ourselves out again. I hope it will make a contribution to a body of literature that, beginning in the late 1950s and early 1960s and developing over the past several decades, has sought to understand the urban settlement rather than condemn it, to study it rather than dismiss it, and to look upon city as human habitat rather than to shun it as alien territory.

The city in its entirety is not, of course, what we shall be exploring here. We shall, as specified earlier, be looking at only one component—but a quintessential one—of the urban settlement form: the public realm. The major burden of this chapter is to sketch the outlines of a geography and history of that realm, as well as to provide a brief overview of subsequent chapters. First, however, two preliminary matters demand our attention.

Preliminaries

Before getting on to the central business of this chapter we need (1) to look briefly at the work of four people who were crucial in challenging social science's conventional wisdom about the asocial character of the public realm and (2) to spend a little time pinning down some working definitions for words that have the unsettling habit of taking on a whole variety of meanings.

Pioneering the Study of the Public Realm

For a social scientist to proclaim in the 1990s that life in the public realm is thoroughly social is merely to proclaim the commonplace, to enunciate the obvious. But, as we have seen in earlier pages, such was not always the case, and the transformation in the perception of public realm activity from "obviously" asocial to "obviously" social was a hard-won victory. There were numerous contributors to this victory and different scholars would undoubtedly single out different clusters of individuals for special mention. I lay no claim, then, that my cluster—composed of Gregory Stone, Jane Jacobs, Erving Goffman, and William H. Whyte—is everyone's quartet of choice, but I think there is no question but that most social scientists would identify all four as contributors and that one or more of my nominees would appear on many lists. None of these scholars, of course, think or thought of themselves as being concerned with the public realm per se: that phrase appears nowhere in their work. And three of them, like most public realm explorers, were simply "passing through" on their way to someplace else. But the observations they made en route and, in one instance, in situ were especially crucial in helping me to see the public realm as a social territory and to see it as one worthy of detailed exploration.

Gregory Stone stepped into the public realm because he was interested in the question of the social integration of urban populations.5 His "City Shoppers and Urban Identification," published in 1954, reported the surprising fact that, for some persons, a degree of integration with the local community appeared to be achieved through an identification with purely economic institutions. Specifically, he found that a portion of retail establishment customers, rather than viewing clerks as either utilitarian instruments or asocial physical objects (as received truth on these matters would have it), infused customer-clerk interactions with meaning and feeling. Or to phrase it in the more technical language of the sociologist, these customers injected elements of primary group relationships into what were "supposed" to be purely secondary relationships. In the obviously anonymous and impersonal world of the city, personalism had been espied.6

Jane Jacobs's concern in The Death and Life of Great American Cities (1961) was with understanding how a city, which she conceived of as a problem in "organized complexity," actually operated. But in pursuing the question of how the various building blocks of the city—its households, streets, local neighborhoods, districts—affected one another and the whole, she devoted over eighty pages (ibid.:29-lll) to a close and textured analysis of the city's streets and parks, or, in other words, to a close and textured analysis of portions of the public realm. Where she "should" have found a social vacuum, she found rich and complex acts, actions, and interactions; what should have been an empty stage turned out to be the setting for an "intricate ballet in which the individual dancers and ensembles all have distinctive parts which miraculously reinforce each other and compose an orderly whole" (ibid.:50). In the obviously anonymous and impersonal world of the city, webs of social linkages had been discerned.

While the aforementioned writings of Stone and Jacobs are landmarks in the study of the public realm, each made only a single contribution to that study, each struck only a single blow, as it were, to conventional beliefs about the realm's asocial character. In contrast, Erving Gofftman struck multiple blows. Goffman, like Stone and Jacobs, meandered into the public realm on his way to somewhere else; in his case, on his way to an elucidation of what he later came to think of as "the interaction order" (1983). But because a fair amount of his interaction order data dealt with people who were "out in public," Goffman almost inadvertently focused his enormous talent for microanalysis on numerous instances of public realm interaction. In much of his work, but especially in The Presentation of Self in Everyday Life (1959), Behavior in Public Places (1963a), and Relations in Public (1971),7 Goffman demonstrated eloquently and persuasively that what occurs between two strangers passing on the street is as thoroughly social as what occurs in a conversation between two lovers, that the same concerns for the fragility of selves that is operating among participants in a family gathering is also operating among strangers on an urban beach. In the obviously anonymous and impersonal world of the city, evidence of ritually sacred interchanges had been unearthed.

Of the four pioneers, only William H. Whyte entered the public realm because that is where he intended to go. While the term public realm is not one he himself has used, since at least the mid-1960s he has been unabashedly interested in the public spaces of cities.8 That interest found some very preliminary expression in the 1968 book The Last Landscape, but it came to full flower in two more recent volumes: The Social Life of Small Urban Spaces (1980) and City: Rediscovering the Center (1988). In these widely read works, Whyte not only confirmed Stone's, Jacobs's, and Goffman's observations of a flourishing public realm social life, he also, and most crucially, began the task of constructing a political argument for the indispensability of public space to the life of the city. Referring especially to that portion of the public realm located in the city's center, Whyte has written:

[T]he center is the place for news and gossip, for the creation of ideas, for marketing them and swiping them, for hatching deals, for starting parades. This is the stuff of the public life of the city—by no means wholly admirable, often abrasive, noisy, contentious, without apparent purpose. But this human congress is the genius of the place, its reason for being, its great marginal edge. This is the engine, the city's true export. Whatever makes this congress easier, more spontaneous, more enjoyable is not at all a frill. It is the heart of the center of the city

(1988:341)

In the obviously anonymous and impersonal world of the city, someone had located not only social life but a socially important life.

Defining Some Terms

As a second and last preliminary matter, it is necessary to spend a little time making clear exactly what I mean by four crucial terms: city or urban settlement, stranger, public (as opposed to private) space, and public realm.

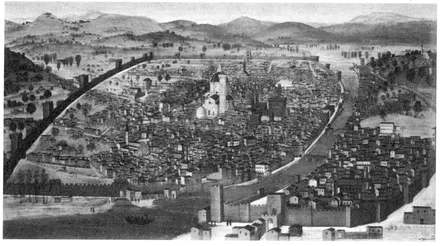

Illustration 1.1. Fifteenth-century Florence. From Toynbee (ed.), 1967.

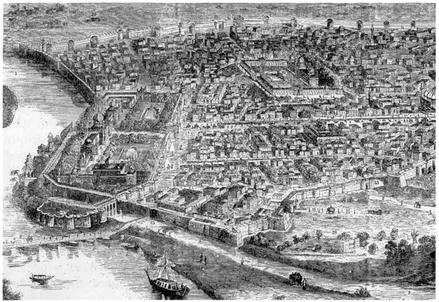

City. There have been times when and there still are places where "city" creates a quite distinct pattern on the landscape. The "large, dense and heterogeneous" settlement—to use Louis Wirth's time-tested definition (1938)—is, precisely because of these characteristics', easily distinguishable from the lightly populated, low density and homogeneous villages that might be near it. It is distinguishable also because it is geographically bounded—clearly separated from other cities and other settlement forms by a visual demarcation—often a wall combined with open space in the premodern period (see Illustrations 1.1 and 1.2); simply expanses of open space in more recent times. For example, in the United States, despite long experience with "suburbanization" (see Fishman 1987; Jackson 1985), up until the late 1930s and early 1940s the political boundaries of most cities were largely coterminous with their visual boundaries.9 In the post-World War II period, however, that initially distinct pattern becomes both less and less distinct and less and less a pattern. With the emergence of the settlement form known as "undifferentiated urban mass" (sprawl, for short), the physical referent for the word city is nothing if not elusive, and, as a not-very-surprising consequence, the everyday language we Americans use to talk about varying settlement forms is nothing if not confusing. Students in my urban courses who were born and raised in the densely populated suburban landscape of California, for example, tell me that they have never "lived in a city." Persons who grow up in metropolitan area settlements of twenty thousand, fifty thousand, or even seventy-five thousand or more, as another example, tell of going off to the "city" and then, exhausted by the pace of city life, happily returning to the "small town" whence they came:10

Illustration 1.2. Delhi in 1858. From Toynbee (ed.), 1967.

Many of those who do return [to the suburbs] are like Clay Fry, who moved back to Lafayette [a Bay Area community of about 23,000] after living in Oakland and working in an architectural office in San Francisco. His life in the urban environment lasted "365 days—almost to the hour," he said. "It was really stimulating, but after a while, the rat race got to me," said Fry, 30, who now works in Walnut Creek [another Bay Area community, population: 58,650]. "I'm used to trees. When I was working in the city, I found myself longing for those days with the trees in the 'burbs."

(Congbalay 1990, emphasis added)

The definitional efforts of people like my students and this young man have their own logic: they are attempts to make sense of the diversity of the built environment within sprawling urban regions or metropolitan areas. For these speakers, the word city is reserved for the largest, oldest, and (usually) the densest of the many named and unnamed settlements within those areas. Similar efforts to use language to "capture" the physical and social heterogeneity of urban areas can also be found in the scholarly literature—the distinctions between and among the terms central city, suburbia, exurbia, and arcadia being a prime example (see, for example, Vance 1972).

The problem with such distinctions, useful as they are for some purposes, is that they obscure the fact of the c...