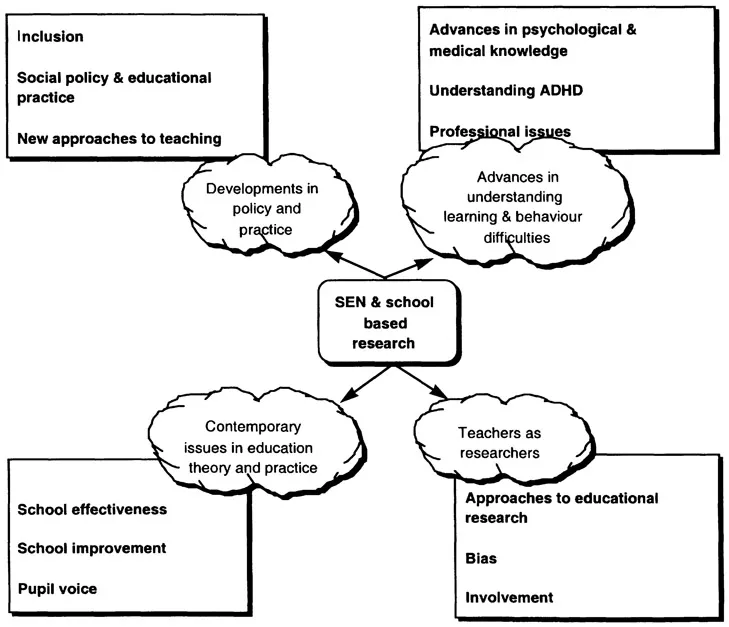

In this chapter we examine four key areas which help to explain why a new book about the use of school-based research as an approach to understanding special educational needs (SEN) may be useful to teachers. These four areas (Figure 1.1) concern:

The following sections focus on significant changes and reinterpretations which have taken place in recent years in each of these areas. Their combined impact makes a strong case for teachers to engage in school-based research as a means of developing and expanding their professional knowledge, understanding and skills so as to help ¿¿//pupils to learn in school, including those identified as having SEN.

Developments in the policy and practice of teaching pupils with SEN

Since the 1981 Education Act, the heated debates about ‘integration in the 1980s and ‘inclusion in the last decade have been accompanied by equally controversial pressures to identify and provide for pupils who, compared to their peers, seem to face particular and persistent difficulties in learning – examples of which include specific literacy difficulties, autism, emotional and behavioural difficulties (EBD) or attention deficit and hyperactivity disorder (ADHD).

Early writers on integration argued for an educational system in which all children had a right to attend a local mainstream school (see, for example, Dessent 1987). Although some children, it was suggested, required special attention and adaptations for their ‘special’ educational needs (usually practical and financial support in the form of additional staffing and/or special resources). More recently, writers such as Hart (1996) have taken a different perspective in suggesting that inclusion requires a new type of ‘innovative thinking’ in which the focus is upon opportunities in the learning environment rather than the special educational needs of individual children (see also, Ainscow 1999; Mittler 2000). Thus, a child may have a learning or behaviour difficulty when it is clear that he or she is expected to learn something or behave in a certain way, in certain circumstances, often within a limited time span (McDermott 1996).

Current SEN policy and practice, as represented in the 1998 Action Programme (DfEE 1998a) appear to be attempting to incorporate both approaches by seeking to develop:

- an inclusive educational system which will both improve the educational opportunities and outcomes for all children;

- a range of special educational provisions to improve educational opportunities and outcomes for children with complex needs or particular types or patterns of difficulty in learning in the ordinary school system.

These goals are often forced into competition with each other in situations where prioritisation of limited educational resources is necessary, or where professionals may have a vested interest in one particular perspective. The experience of working with individual pupils in school can highlight the difficulty in balancing the urgency of coping with pupils’ immediate needs against the longer-term changes to legislation, policy and practice. Yet the two goals do not need to be in opposition. We would argue that to focus on either the context 0rthe individual child can result in a wasteful division of effort in both teaching and research. Recent understandings of SEN bring together an interest in how individuals and groups of children learn in different contexts (see, for example, Norwich 2000; Skidmore 1999a; Clark et al. 1998; Hart 1996). Teachers can be involved in examining how policy and practice in a school may create or prevent SEN alongside making decisions for individual pupils in the light of the increasingly sophisticated knowledge of why certain children have persistent difficulties in learning.

The 1998 SEN Action Programme (DfEE 1998a) was pragmatic in recognising the limitations of a broad policy of inclusion which does not take individual circumstances into account. The government found in the responses to the previous Green Paper Excellence for All Children: Meeting special educational needs (DfEE 1997) that:

Many, particularly practising classroom teachers, were concerned that we should not underestimate the real challenges schools face in becoming more inclusive. Our approach will be practical, not dogmatic, and will put the needs of individual children first, (p. 23)

So, what challenges do schools face and how can the needs of individual children be identified in different school contexts? These questions need investigation – the answers are not easily understood or agreed. In considering the role of school-based research in this area we need to recognise the changes taking place at different levels of the education system and the interactions between them.

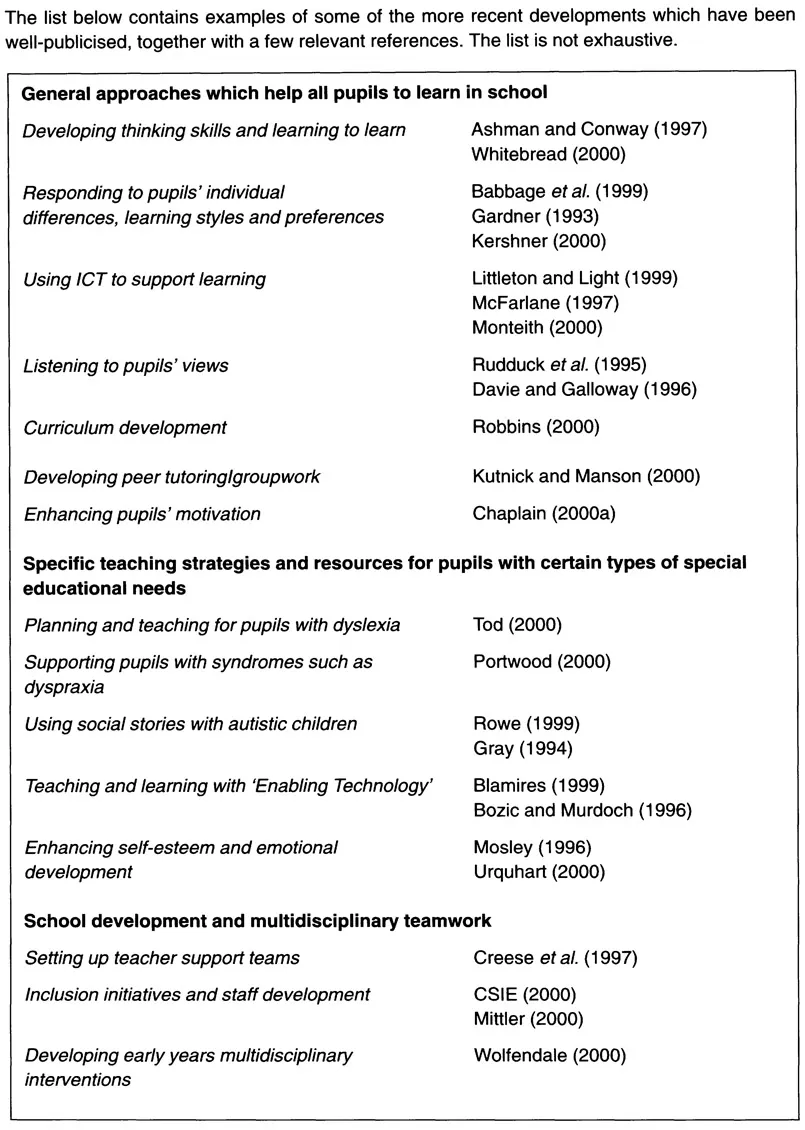

There have been a number of recent developments in the field of special educational needs and allied’ provision. Some of these developments have resulted from changes to policy, practice and attitudes towards the education and care of children with special educational needs; while others reflect advances in mainstream medical and psychological research and practice (see Table 1.1 for examples). Some changes to educational practice come in the form of central government directives to schools, (e.g. from the Department for Education and Employment (DfEE), Department of Health (DOH) and Home Office) others from initiatives which reflect more local concerns.

Social policy and educational practice – a suitable case for research?

While a number of developments and directives reflect the findings of empirical educational research, others are driven by changes to economic and social policy. A recent example of the latter comes from concerns about children’s rights and equal opportunity legislation. The Children Act 1989 for example, heralded a new status for children. Subsequent guidance and further changes had significant outcomes for professionals working with children generally and, in particular, those working with the most vulnerable children. Staff working with children who exhibit challenging behaviour for example, are aware of the ongoing debate regarding restraint of those individuals perceived to be out of control and a danger to themselves or others. This debate has involved both educational and social services departments and led to the formulation of guidelines in local authorities on permissible forms of physical interventions with children and young people (see, for example, DfEE 1998b; DOH 1993; DfEE 2000a).

This concern is not limited to special educational needs, but is part of a bigger picture. We are made increasingly aware of difficulties outside education regarding what constitutes ‘reasonable force’ and where and when not to intervene with individuals breaking social codes with their behaviour – for example; military peace keeping, policing of demonstrations and protecting oneself from personal attack. This bigger picture reflects changes to human rights and to the execution of the law, including substantial changes to individual rights, litigation and compensation. For the teacher in a classroom these issues can appear to have little if anything to do with what they are faced with on a daily basis. However, the level of public interest and monitoring of service delivery and professional practice currently taking place in schools in the form of OFSTED, alongside accountability to parents and governors, tends to contradict such thinking.

From a research perspective, analysing the ‘big picture’ and relating it to a more local context can be quite illuminating. In their book, Caring Under Pressure (1994), Chaplain and Freeman related the very local experiences of young people in residential schools to the wider issues of welfare justice and a historical perspective. In so doing, political rhetoric and official recommendations were contrasted with the reality of practice. Furthermore, these observations were analysed within a historical frame which highlighted those areas where progress had been made and those which had marked time.

This unpacking of rhetoric from reality, especially the translation of political ‘fantasy’ into workable practice for professionals, is familiar rather than novel in some areas of social science. In fields such as special education, given the relatively small populations of those involved, this can sometimes appear more difficult to do. However, prospective researchers should not be put off analysing the effects of policy changes on professional practice within, and across disciplines. Researching the effects of change can prove an interesting (if often sensitive) area of study. While change can be motivating for those involved, it can also prove stressful requiring the development of new coping strategies and new ways of working.

Table 1.1 New approches to teaching pupils with SEN

Advances in the understanding of learning and behaviour difficulties

There have been a number of advances in psychological, medical and educational research which have the potential to change the way in which teachers (and other professionals) perceive, investigate and intervene with children who have special educational needs. These advances include, for example: cognitive functioning vis-à-vis the enhancement of academic achievement among children with SEN (Adey and Shayer 1994); overcoming the limitations of motor difficulties using conductive educational methods (Sigafoos et al 1993); cognitive models of ADHD (Rutter 1989); cognition and achievement motivation (Galloway et al 1996) and metacognition and hearing difficulties (Al-Hilawani 2000). See Table 1.1 for further examples.

However, while a number of professionals research SEN, they often come to very different conclusions about the causes of, and how to respond to, learning and behavioural difficulties. As an illustration of such differences we will examine the professional discourses in one area of SEN in more detail. In the next section we discuss some of the psychological, medical and educational research findings and debates surrounding an area which has attracted considerable interest from both professionals and lay persons, that is, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD).

ADHD – A problem of definition?

Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder is defined by Cooper and Ideus (2000) as:

… a medical diagnosis that is applied to children and adults who are experiencing significant behavioural and cognitive difficulties in important aspects of their lives (e.g. in their familial and personal relationship; at school or work). These difficulties can be attributed to problems of impulse control, hyperactivity and inattention, (p. 1)

ADHD is one of a cluster of terms relating to behaviours displayed by sufferers such as, inattention and difficulties regulating impulsiveness. As in some other areas of SEN, behaviour difficulties are difficult to define — and ADHD is no exception. Anyone familiar with the literature concerned with the definition and aetiology of maladjustment or emotional and behavioural difficulties will understand that precise definitions in this area are elusive to say the least (see Laslett 1983; Chaplain 2000b).

Attempts to explain the aetiology of ADHD are wide-ranging and often controversial as are debates about treatment, especially in respect of using medication to manage children’s behaviour (see, for example, www.attention-deficit-disorder.org). The field has attracted the interest of a number of research communities including psychiatrists (e.g. Rutter 1989), psychologists (e.g. Braswell and Bloomquist 1991) and educationalists (e.g. Cooper and Ideus 2000). Explanations include social construction; mild brain damage and multi-modal perspectives.

The causes of ADHD – professional discourses

According to Tannock (1998), ADHD occurs more frequently among the biological relatives of children diagnosed as having ADHD compared with the incidence among relatives of other children. This has led some writers to argue that ADHD might somehow be inherited. In response, critics of this view argue that controlling for environmental factors which families are likely to experience or share, such as stress or poverty, is difficult. Nevertheless, investigators have acknowledged an association between a clear genetic anomaly and individuals identified as having ADHD (Hauser et al. 1993). Gene structures in the Dopamine system (which is concerned with regulation of the mind) appear to be important in distinguishing between individuals who have ADHD and those who do not (Thompson 1993). Beyond debates about causality are those related to treatment, particularly in relation to the use of drugs to control behaviour. The use of psychostimulants (e.g. Ritalin) to control the behaviour of children with ADHD, has sparked off a heated debate among a number of professionals and parents. These drugs have remarkable effects — usually within an hour of swallowing a single dose the child becomes more obedient, more focused and more willing to concentrate on tasks and instructions. Those having difficulty with a child can simply administer a tablet and he/she will become less trouble-some. While the appeal of using such drugs might be to offer some respite to those having to cope with the child, the side effects are considered unacceptable by many professionals. These effects, according to Breggin (see, www.breggin.com/Ritalinprnews.html 2000) include the child becoming zombie like’, withdrawn and depressed. He adds that they can also produce drug-induced behavioural disorders such as psychosis, mania, drug abuse and addiction.

A small number of neuroimaging studies (e.g. using electroencephalography) have found a relationship between abnormalities in the striatal regions of the brain and some individuals with ADHD (Cooper and Bilton 1999). However, Barkley (1997) suggests that neuroimaging research has failed to establish evidence of brain damage as a cause of ADHD. He argues that where brain abnormalities have been found to correlate with ADHD they result from abnormal neurological development.

Barkley (1997) offers a cognitive model to explain ADHD that emphasises a lack of impulse control, and problems with self-regulation. Put simply an individual with ADHD lacks the ability to maintain focus on longer-term goals because immediate goals overpower them. This is not to suggest that such individuals are not consciously aware of the value of longer-term goals. For example, a child may well recognise the advantages of sharing and taking tu...