eBook - ePub

Simulation of Recreational Use for Park and Wilderness Management

This is a test

- 220 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Simulation of Recreational Use for Park and Wilderness Management

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

First Published in 2011. This book describes the application of an advanced analytical technique, simulation modeling, (WUSM) to a significant problem in resources management. It includes ideas which have grown out of practical resource management problems that have progressed through conceptual models to operational tools and finally to application in actual public land management settings. It is similarly rewarding to see the work being adapted for use by the National Park Service and other agencies at home and abroad.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Simulation of Recreational Use for Park and Wilderness Management by Mordechai Schechter, Robert C. Lucas in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Droit & Droit de l'environnement. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1

Introduction

The Issues

Wilderness remains wilderness only as long as man and his traces are few. Two conditions are necessary for an area to qualify as wilderness—essentially unmodified natural ecosystems and outstanding opportunities for solitude.

Both of these qualities are specified in the two Wilderness Acts in the United States, and are also prominent in public attitudes and perceptions. The policies of the agencies responsible for managing these wilderness areas stress these conditions, and management plans for individual areas focus on ways of protecting both.

By early 1978, 175 areas and 16.6 million acres (6.7 million hectares) had been legally designated as wilderness. For these areas, which are located in 39 of the 50 states, the threat of degradation of natural ecological conditions and loss of opportunities for solitude comes almost entirely from recreational visitors. Many other areas, although not officially established as wilderness, also are valuable for low-density recreation. Maintaining natural conditions may not be a critical management goal in all these areas, but some desired level of solitude is, and, again, overuse is the threat.

It is widely recognized that a wilderness has a limited carrying capacity which cannot be exceeded without destroying the qualities that characterize it. Management of recreational use is essential to protect wilderness qualities, but such management is a difficult challenge. The Wilderness Use Simulation Model presented in this book (usually referred to hereafter simply as "the simulator" or by the initials "WUSM") is one tool for strengthening management of wilderness use.

For readers unfamiliar with American wilderness, some background may be helpful. Starting in the 1920s, areas in the national forests were administratively designated as primitive areas, wild areas, or wilderness. Later, legislation (Public Law 88-577, 1964) endorsed and extended wilderness classification to include national parks and wildlife refuges. Wilderness areas were designated in the longer settled and more extensively developed eastern states still later (Public Law 93-622, 1975). Many wilderness areas are large—often from 100,000 to over 1 million acres or about 40,000 to 400,000 hectares—and most are in mountainous regions in the western United States. These areas serve as nature preserves but have always also had great importance as recreation areas. They are most commonly used for hiking, often just for the day, but other times for several days or a week or two, which involves overnight camping, usually at campsites with little or no development. Simple trails wind through the areas. Some visitors travel on horses, and, in a few areas, by boat, raft, kayak, or canoe. There is some winter use on skis or snowshoes. Generally, roads, commodity production, permanent residences, and use of mechanical devices are prohibited. For a good description of many of these areas, their use, and some of their management problems, see Wilderness U.S.A., published by the National Geographic Society (1973). Many other countries have roadless recreation areas, often in national parks or nature reserves, which share many of these features and problems.

The Need for Wilderness Use Management

The recreational use of wilderness has been growing steadily for many years. Figures for national forest wilderness, which includes most U.S. wilderness, show an average annual increase in use of just over 7 percent for 1960-75. From 1946 to 1959, the average annual increase was almost 15 percent.1 Figures available for the wild backcountry of some national parks for various periods also show rapid increases in use. For example, backcountry use of Rocky Mountain National Park increased over 700 percent in the past ten years.2 Shenandoah National Park's backcountry use quadrupled from 1967 to 1974.3 A continued growth in the numbers of people visiting wilderness and similar areas is expected in the future, and even if the growth rate is less spectacular than in the past, it will intensify the need for management of use. Even if use should level off, as it eventually will, the need for skillful, professional management will still exist.

Use of individual wildernesses varies greatly. Visitor-days4 per acre for national forest wildernesses vary from a low of 0.01 to a high of 7.59, a 750 to 1 range. (See table 4-1 in chapter 4 for some examples of use intensities for various wildernesses.) In many areas, use pressures are high, and there is general agreement that excessive use is damaging natural conditions or eliminating solitude, or, in most cases, harming both. The distribution of recreational use within a particular wilderness is also usually very uneven. Many of the areas not heavily used in total still have parts that are crowded, with resulting loss or reduction of wilderness qualities.

Research on how visitor use affects ecosystems leaves no doubt that damage to natural conditions is a problem. Studies so far show that a small amount of use usually has a large initial impact on soils and ground cover vegetation, but that additional use has proportionately less and less impact (Merriam and coauthors, 1973; Frissell and Duncan, 1965; Bell and Bliss, 1973; Dale and Weaver, 1974). Damage can occur quickly, but recovery is slow. Water quality may be affected by recreational use in a more linear manner, although changes appear small, but research is scanty (Merriam and coauthors, 1973; McFeters, 1975). The effect of recreation on wildlife is virtually unstudied (Stankey and Lime, 1973). Current knowledge identifies no obvious, critical use level or naturally occurring threshold on which to base ecological carrying capacities. Professional managerial judgment will be needed to determine how much change in natural conditions can be accepted as consistent with wilderness management objectives (Frissell and Stankey, 1972). The severity of impacts and the ability of the ecosystem to recover are the main issues. Much of the potential management response to visitor impacts probably will involve closing trails and campsites located on fragile lands and relocating them to more durable settings where possible (Helgath, 1975). Water quality may be managed by changing methods for disposal of human wastes. Still, for many specific places, managers will need to set upper limits on use to keep environmental impacts to acceptable levels.

Studies of wilderness visitors' desires and attitudes concerning solitude also support the conclusion that overuse can damage wilderness experiences. Solitude, or more precisely, meeting few other parties, is an important appeal of wilderness for most visitors (Stankey, 1973). More use and more encounters with other groups result in less expressed satisfaction, but many factors interact to modify the effect of encounters on the quality of the experience. Most visitors preter a campsite out of sight and sound of other visitors, but tolerate a few encounters on the trail before their reported satisfaction drops much. Encounters are more acceptable close to entry points than in the interior of a wilderness. Large parties disrupt solitude far more than small groups do. Some hikers object to meeting visitors traveling with horses.

Wilderness visitor studies indicate there is a sort of tradeoff between quantity (number of visitors) and quality (satisfaction with the experience). We can think of this in terms of diminishing returns. Total benefits would rise as use increased at low levels, because more people would enjoy the area, and enjoyment or benefits per visitor would remain high. But, at some point, increasing use would result in congestion and enough encounters to reduce the benefits per visitor so much that total benefits level off. Continued increases in use would lower total benefits (Fisher and Krutilla, 1972).5

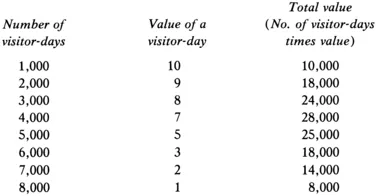

Perhaps a simple, numerical example will clarify the idea. Imagine a wilderness where the value or benefits of a visitor's experience can be measured for a variety of possible use levels. How it is measured or what the units are, we can leave to the imagination (of course, it could even be how much people would be willing to pay to enter):

In the example showing diminishing returns, total benefits rise at first and peak at 4,000 visitor-days. This is the optimum use level. It clearly would make sense to keep use from exceeding approximately 4,000 visitor-days.

Studies of wilderness visitors support the validity of the concept.6 Satisfactions, benefits, values—whatever term we choose—per visit decline as use increases and solitude diminishes. At some level, limiting use can keep total benefits from declining.

Most visitors seem to recognize this; they generally support the concept of limiting use to protect wilderness qualities (Stankey, 1973). Some rules of thumb suggest solitude or encounter goals, even if not optimum use levels. No camp encounters (i.e., an isolated camp out of sight and sound of other parties), at least a substantial part of the time, and daily trail encounters with other parties that do not often exceed two or three look like possible interim objectives (Stankey, 1973), but, as with ecological impacts, managerial judgment is still indispensable.

Although the general idea of use limitation is well accepted, particular techniques to limit or ration use are controversial, and any such scheme needs to be soundly conceived and well justified. Much also can be done to try to reduce impacts on both the ecosystem and other visitors' experiences. Rationing should be a last resort, but in many places eventually it will be necessary.

In fact, use is being rationed already in many wildernesses, by both the National Park Service and the USDA Forest Service. The systems used are varied. Some limit only the number of overnight visitors, and others control both day use and overnight visitors. Managers in some areas limit the number of parties entering per day, and, in other areas, they try to control the number present each night. Sometimes permits can be reserved in advance, and sometimes they can be obtained on a first-come-first-served basis; often, a mixture of the two is used.7

Rationing is under serious consideration for other wildernesses. At the same time, many wilderness managers are trying to cope with overuse problems in other ways and thus postpone or avoid the need to ration use. There are efforts to modify use distributions by giving visitors information about congested areas and alternative locations, and by encouraging some visitors to come during off-seasons or during midweek when use is down. If visitors' skills, knowledge, and sensitivity can be improved, their effect on soils, vegetation, and other visitors' solitude can be cut down, and more visitors can be accommodated. These are all very worthwhile management efforts, and they should precede a decision to ration use. But, for many popular places, limitations on use cannot be postponed indefinitely.

Weaknesses in Use Management Planning

As we have just indicated, there is some research base to help a wilderness manager set goals for use levels and encounter frequencies that will protect ecological conditions and solitude. The problem comes in taking the next step and deciding how much use can be permitted without exceeding these goals. This is because use patterns are the complex, variable result of innumerable individual choices that produce overlapping routes with unforeseen interactions.

It is extremely difficult to predict use levels at specific places, given a total use level and pattern of entry-point use. Encounters are even more difficult to predict—in fact, it is apparently impossible on the basis of experience and intuition. No formula gives the answer.

This means that the establishment of use limits or even efforts to modify use distributions indirectly, without rationing, must be based on rather rough approximations that have a large, arbitrary element. It is often likely that there still will be too much use and too many encounters in parts of an area, and that some visitors will be unnecessarily denied entry elsewhere—perhaps in the same wilderness.

There is one way to avoid this problem, although it has other serious disadvantages. This is to control visitor movements within an area. The route of travel and the camp locations to be used each night can be specified on the visitor's permit. Use levels at any location could be kept within capacity goals. Campsite encounters could also be controlled. Trail encounters would still be difficult to predict and essentially uncontrolled, unless travel was very tightly scheduled.

The disadvantage is the serious loss of visitors freedom, sense of exploration, and spontaneity, all of which are important wilderness values. In fact, the 1964 Wilderness Act mandates "free and unconfined recreation." A parody in a hikers' magazine years ago described an area in the future where visitors' routes and speeds were all programmed for them, where so many seconds were scheduled for absorbing a scenic vista, and where an unauthorized delay to view a sunset could be grounds for expulsion. Such control (not as complete as in the parody, of course) could maximize use of an area while minimizing encounters, but it seems like a high price to pay. Visitor surveys indicate controlled itineraries are the most unpopular way to limit use (Stankey, 1973).

The administrative costs for tight control of wilderness visitors' itineraries also are likely to be high. Enforcement requires heavy patrolling and is difficult. Departures from the specified route often occur because of extenuating circumstances—weather, illness, or accidents, for example—and the wilderness ranger must make difficult decisions on when to enforce and when to waive regulations.

Another approach is to limit total use, often with daily quotas for entry points, but to allow visitors a free choice of route within the area. This preserves freedom to roam and explore, and choose campsites spontaneously. Administrative costs are probably lower than for controlled itineraries. The enforcement load is much less, and visitor acceptance is better. This approach has the problem referred to earlier. In most cases, the on-the-ground results in terms of amount of use (as related to environmental damage), and encounter and solitude levels cannot be predicted. Flows of visitors diverge at some places as trail systems branch, and then, at other places the flows converge as traffic from different entry points overlaps. This pattern of visitor movement is usually far too complex to permit calculation or prediction of use patterns. There are possible exceptions, of course, such as a dead-end trail up a steep canyon to one camping area, in which use patterns and camp encounters would be reasonably predictable. However, trail encounters are further complicated by variability in starting times and speed of travel, and are beyond our ability to predict under any conceivable, realistic conditions. Predicting the overall use patterns of new trails or trail closures, new camp areas, new entry points, and so on is even more difficult. Some method for dealing with these complexities is needed.

Trial-And-Error Approach

The only method that has been available to deal with the problem of unpredictability so far has been trial and error. Use limits would be ba...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- LIST OF FIGURES

- LIST OF TABLES

- FOREWORD

- ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

- CHAPTER 1 INTRODUCTION

- CHAPTER 2 WHAT IS SIMULATION?

- CHAPTER 3 THE WILDERNESS USE SIMULATION MODEL (WUSM)

- CHAPTER 4 THE DESOLATION WILDERNESS

- CHAPTER 5 INPUT DATA

- CHAPTER 6 VALIDATING THE SIMULATOR

- CHAPTER 7 STRATEGIC AND TACTICAL CONSIDERATIONS IN EXPERIMENTING WITH THE SIMULATOR

- CHAPTER 8 FORMULATING AND TESTING USE MANAGEMENT POLICIES

- CHAPTER 9 AN APPLICATION OF THE SIMULATOR TO A RIVER RECREATION SETTING

- CHAPTER 10 THE POTENTIAL OF THE SIMULATOR AS A MANAGEMENT, RESEARCH, AND EDUCATIONAL TOOL

- APPENDIX I USING WILDERNESS PERMITS TO OBTAIN ROUTE INFORMATION

- APPENDIX II AN OUTLINE OF NECESSARY STEPS AND ESTIMATED COSTS TO SET UP THE WILDERNESS USE SIMULATION MODEL FOR A TYPICAL WILDERNESS RECREATION AREA

- APPENDIX III COST CONSIDERATIONS IN RUNNING THE SIMULATOR