- 183 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

The method of programming outlined in this book represents a major contribution to the growing body of literature in programmed learning. It is the first book in the field to present a carefully designed, complete and integrated system for analyzing, organizing and structuring learning materials in programmed form.Application of the system is illustrated through the step-by-step construction of two short programs. Starting with the analysis of the syllabus and course content, the authors take the reader through each phase of the programming process gathering and organizing the content material, construction of the program matrix and flow diagram and finally, the writing of frames.Every teacher and trainer can benefit from the application of this method to lesson plan preparation and to classroom teaching techniques. Such a method is essential, for all those who are writing programmed materials. In a new computer age classroom environment, programmed learning can be especially beneficial.C. A. Thomas, I. K. Davies, D. Openshaw, and J. B. Bird are instructors or directors at the British Royal Air Force School of Education. They are pioneers in the application of programmed learning in Britain and are highly regarded as forward looking and creative educational research workers. Their accomplishments include, in addition to this ingenious book, the design and development of the Empirical Tutor, one of Britain's major teaching machines, and the publication of a number of technical papers in the field of programmed learning.Lawrence M. Stolurow is professor emeritus of psychological & quantitative foundations at the University of Iowa.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Section 1 Education—Today and Yesterday

To maintain unity yet encourage diversity; to give equality of opportunity yet nurture ability; to achieve high standards yet avoid the narrowness of mind inherent in specialisation; to be efficient yet remain humane: these are at all times tasks of extraordinary difficulty. In an age of political and social revolution of which no one can see the outcome, they become infinitely more so.

H. C. DENT, British Education

Chapter 1 The Problem of the Educationalist

Progress in education cannot be separated from the economic, social and political changes which are taking place in the world. All are intimately linked together and must progress together if man is to achieve mastery over his environment and enjoy the benefits of an advancing civilisation. During the present period of rapid scientific and technological progress, society is in grave danger of paying more attention to the means rather than the ends of education. It is therefore essential that we should re-examine and restate our aims in education in relation to the contemporary world.

Professor M. V. C. Jeffreys in his book Glaucon—An Inquiry into the Aims of Education emphasises the value of human personality and defines the primary purpose of education as ‘the nurture of personal growth.’ He also points out that education is not an isolated process but must be seen in relation to the problem of living as a responsible and privileged member of society.

If we analyse the definition ‘nurture of personal growth’ we see that it implies that education is a threefold process: it involves nurture or guidance within a favourable environment; then there is the personal process of self-fulfilment in the mental, spiritual and physical development of the individual; finally the process of growth results in the full and balanced development of the individual to adulthood, when he is able to take his place in the society in which he lives.

This analysis constitutes a careful and precise definition of the role of the teacher. We can, therefore, regard teaching as an ‘enabling process’. The teacher’s task is to guide the student through experiences in a controlled environment, allowing him to form his own opinions, carry out evaluations and make his own judgments. The teacher must not dominate or obtrude into the process of learning; rather he should act as a catalyst. He should create an environment in which the student finds it easy and interesting to learn, and should introduce order into the learning process to prevent it from being a haphazard and chaotic experience.

Unfortunately, such a learning and teaching situation is difficult to attain in our modern world. Although science and technology have completely revolutionised many facets of our western society, education has not derived commensurable benefits. We suffer from straitened economic circumstances which prevent us from expanding and improving the quantity and quality of education, and from an almost complete absence of serious educational research. In 1962, for instance, it has been estimated that a sum of not more than £100,000 was expended on educational research projects; this is only slightly more than the amount spent during the same period on research into whitewash.

At the present time we are faced with a critical shortage of teachers and instructors, insufficient accommodation, inadequate facilities and equipment, and a training programme for teachers which is unlikely to produce the trained personnel to meet the ever-increasing demands for education and training. The position is further aggravated by a tendency to cling to teaching methods and techniques which have proved to be inefficient, ineffective and uneconomical and which cannot be reconciled with our present economic and social needs.

Emphasis has been placed upon the importance of ‘teacher-teaching’ at the expense of ‘learner-learning’ which has been relegated to an inferior and unimportant place. Learning cannot be regarded as a synonym for being taught yet, despite the pleas of educational reformers, we have tended to concentrate our attention on teacher performance to the detriment of the student’s natural capacity to learn for himself. Although many teachers and psychologists would disagree as to the exact nature of the learning process, there are certain principles of learning upon which most educationalists would agree. Alvin C. Eurich of the Ford Foundation recently summarised these as follows:—

(a) Whatever a student learns, he must learn for himself—no one can learn for him.

(b) Each student learns at his own rate, and for any age group the variation in rates of learning is considerable.

(c) A student learns more when each step is immediately reinforced.

(d) Full, rather than partial, mastery of each step makes total learning more meaningful.

(e) When given the responsibility for his own learning the student is more highly motivated; he learns and retains more.

As a result of their teaching experience, the authors would like to add:—

(f) Whatever has to be learnt must be made meaningful in terms of the student’s own experience and should be appropriate to his age, aptitude and ability.

(g) The student should be encouraged to develop his own innate capacity for creativity.

If one accepts these principles, one must concede that the conventional class-room situation is inefficient. All the goodwill in the world, together with a passionate sense of vocation and the use of well-known and widely accepted class-room techniques cannot, however, prevent the teacher from violating some of these principles. However, modern developments in technology offer the possibility of more effective communication whereby the student can be so stimulated that his education progresses at his optimum rate. To rely too much upon teachers and books is to deny the student the benefits which accrue to contemporary society as a result of man’s constant search for knowledge.

The problem facing the educationalist today is that of finding the best way of harnessing recent advances and achievements in science and technology in order to enrich the personal experience of his students, and so create an environment in which the accepted principles of learning can be realised.

Chapter 2 The Teaching Situation

The population of the world is increasing at an alarming rate and more and more people are demanding education as their inalienable right. To support this increasing population, economies have to be strengthened and this process is dependent to a large extent upon efficient industrial training. Industrial training naturally forms part of the tertiary stage in the British educational system and must be fully integrated with it. The primary, secondary and tertiary stages of education can be viewed as being built around a ‘common core’ of the knowledge, skills, techniques and attitudes necessary to the preservation of our cultural and economic life. The problem is, how can we achieve this without letting students become, increasingly, merely passive participants in the training process.

Most practising teachers will agree that the ideal teaching situation is one teacher to one student where the student and the teacher participate and co-operate together in the learning process. In this tutorial or ‘Socratic’ method, the function of the teacher is that of a guide who presents the student with situations and problems suited to the latter’s needs and capabilities. In this situation the teacher has the responsibility of bringing the student into direct contact with knowledge (Fig. 2:1) and must ensure that the material is presented in such a fashion that the student can employ his capacity for logical analysis.

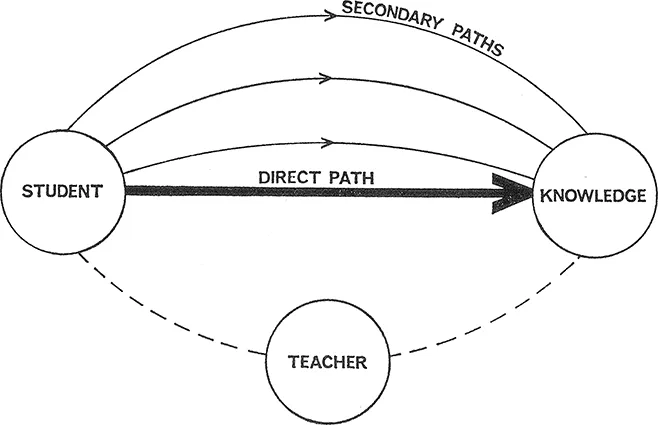

Fig 2 : 1—Paths to Learning.

Fig. 2: 1 illustrates the position of the teacher who does not obtrude into the process of learning but is sufficiently in contact with the situation to be able to influence it. In the absence of the teacher, learning would still be achieved, provided that the student was sufficiently motivated, but there would be no guarantee that he would follow the efficient and optimum direct path. He might well follow one of the secondary paths to learning which, as the figure indicates, would be less direct and probably more difficult to traverse.

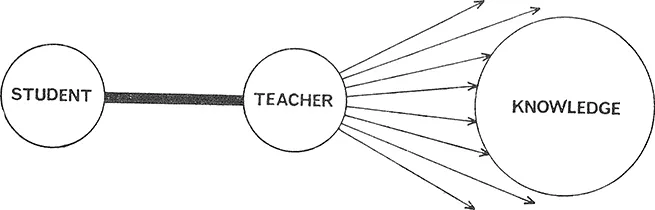

Fig 2 : 2—The Obstructionist

Fig. 2:2 illustrates the situation resulting when the teacher obtrudes into the learning process. In this case, the student is prevented from having direct contact with reality and has to rely entirely upon the teacher’s interpretation (or misinterpretation) of the subject matter. The student is made to rely upon the extent of the teacher’s knowledge and understanding of the subject, which may be extensive or sketchy. The student also has to rely upon the teacher being able to express his knowledge in words which are meaningful. Instead of helping the student to master the situation, the teacher can diffuse and distort the pathway to such an extent that the student is utterly confused, learns nothing, experiences failure and associates his failure with the subject, which he will consequently dislike. The drudgery and frustration often associated with mathematics, science and foreign languages is a direct result of such a situation.

In the more favourable situation depicted in Fig. 2: 1 the teacher influences the process of learning by organising and ordering his material in the light of the responses made by the student. This process of communication between the teacher and the student is called feedback. It is the most important feature in the tutorial system because it allows the teacher to be infinitely flexible in deciding the most appropriate approach to, and rate of development through, the subject matter. At the same time, the student is constantly being challenged and is personally involved in the situation. He has, therefore, to be adaptable. The tutorial method, therefore, enables differences in student intelligence, ability and aptitude to be provided for. It must be recognised that Figs. 2:1 and 2:2 are gross oversimplifications of a very complex relationship. A more detailed analysis of the teaching process is depicted in Fig. 2:3.

The teaching process must be student-orientated and, as teachers, we make two basic assumptions:—

(a) that the student has a memory;

(b) that the student has a capacity, no matter how limited, for logical analysis.

When we prepare our lessons we keep these two attributes in mind and aim to present the student with a situation in which he can employ them. If we gauge the attributes accurately, our lesson is likely to be successful; if however we over- or underestimate them, communication is certain to be ineffective.

When deciding his lesson plan, the teacher uses his own memory. He will recall such things as: subject matter; profiles of students (individual characteristics and personal histories); past experiences when teaching the subject; previous methods and techniques adopted and their relative success; topical and anecdotal information; objectives of the course of study (examination requirements, syllabus content).

As a result of this analysis, the teacher produces a basic teaching plan, which we shall call his strategic teaching plan, in the full understanding that this will have to be modified as the lesson progresses. The material in this plan must be so organised that it will help the student to master the subject and achieve success, thus increasing his motivation.

The teacher starts his lesson by presenting a stimulus to the student which will provide a challenge. This will cause the student to call on his memory and his capacity for analysis, and so evoke an overt response. This response is fed back to the student’s memory for future reference and serves as a form of partial reinforcement. At the same time, it is noted and evaluated by the teacher who informs the student whether he is right or wrong, thereby providing additional reinforcement.

Having carried out this evaluation, the teacher must now consider the next step in the presentation of the lesson. Calling upon his previous experience of teaching the subject, he may well decide that a change in his original teaching plan is now necessary because of the nature of th...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Programmed Learning in Perspective

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- SECTION 1. Education Today and Yesterday

- SECTION 2. Programmed Learning and Teaching Machines

- SECTION 3. The Construction and Writing of Programmes

- SECTION 4. Programmes in Perspective

- Selected Titles on Programmed Learning

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Programmed Learning in Perspective by I.K. Davies in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Education & Education General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.