eBook - ePub

Working for Children

Securing Provision for Children with Special Educational Needs

This is a test

- 227 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Working for Children

Securing Provision for Children with Special Educational Needs

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

First Published in 1996. The last 15 years have seen major changes in the way in which children with special educational needs are considered and taught. This book explains the current approach by reference to the developments in the recent past; consider some of the issues involved in identifying and assessing children who may have special educational needs; describes the SEN provision which can reasonably be expected to be made by schools and the statutory duties of the Governing Body; looks at funding; statements of Special Educational Needs and how to appeal and complain to governing bodies such as SEN tribunal, Ombudsman, and the Secretary of State.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Working for Children by Peter Bibby, Ingrid Lunt in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Education & Education General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1

Special Needs and Provision

Introduction

The last 15 years have seen major changes in the way in which children with special educational needs are considered and taught. This chapter explains the current approach by reference to the developments in the recent past.

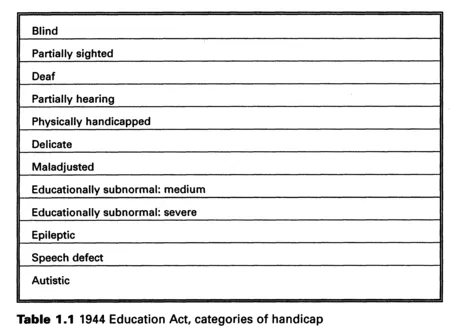

Before 1978

The 1944 Education Act established 12 categories of handicap (or 'defects of body or mind'). Educational provision was made, usually in segregated special schools, according to the children's category of handicap, as shown in Table 1.1. Before 1971, one group, the 'severely subnormal', were deemed to be 'ineducable', and therefore the responsibility of the health rather than the education authorities. In 1971 responsibility for their education was transferred from the health authority to the education authority, with significant changes in the way that provision for these pupils was made.

Following arrangements set up in 1975, children deemed to be in need of special education were formally assessed by a medical officer, an educational psychologist and the school and were 'ascertained' as having a certain kind of handicap. After assessment they were almost always placed in the appropriate special school.

The categories of handicap served as labels, and the segregated and very separate provision in special schools meant that these pupils usually had no contact with their mainstream peers. The curriculum in special schools was often so different from that of mainstream schools that pupils rarely returned to mainstream. Prior to the Warnock Report of 1978, the number of pupils ascertained as requiring special education

Table 1.1 1944 Education Act, categories of handicap

was less than 2 per cent of the school population. This corresponds with figures from other Western countries, which suggests that most countries find it difficult to meet the needs of about 1.75 per cent of the school population in mainstream schools.

Observations

Four points may be noted here.

1 Special Schools

Special provision almost always meant segregated special school. Thus, children ascertained as handicapped were placed in a special school according to the category of handicap. For example, 'maladjusted' pupils were placed in schools for maladjusted pupils.

2 Borderline Categories

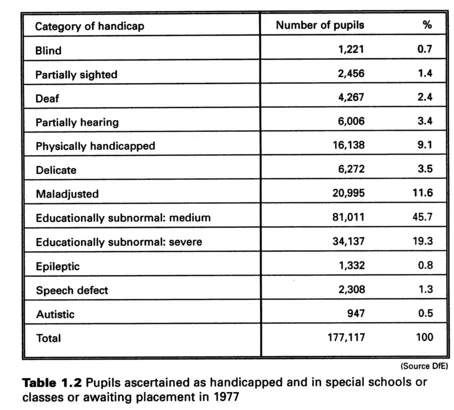

A significant majority of pupils in special schools fell into the categories of 'maladjusted' and 'moderate or medium educationally subnormal (ESN(M))', as compared with the other categories; see Table 1.2. These groups, the so-called 'borderline' categories, are difficult to identify and

Table 1.2 Pupils ascertained as handicapped and in special schools or classes or awaiting placement in 1977

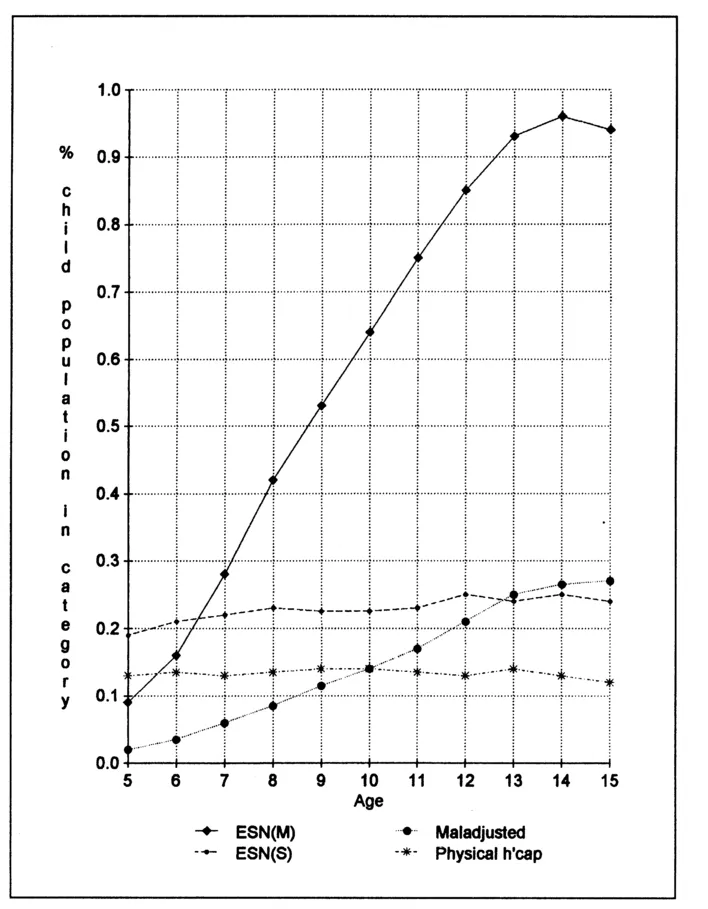

define with any objectivity, and consist of pupils whose special needs are very often the result of a range of factors including socio-economic background. Furthermore, the size of these groups increases with pupils' age, indicating a multiplicity of interacting contributory factors; see Figure 1.1.

3 The 2 per cent in Special Schools

There was nothing absolute about the figure of 2 per cent. This represented the availability of special school places in London at the time when the first educational psychologist, Cyril Burt, devised this system. The level of disability which merited placement in special school was agreed to be a level or score of more than 2 standard deviations below the mean of a standardized test, or an IQ score of below 70, according to commonly used IQ tests. This again had no greater significance than that of producing the appropriate number of pupils for the places in special school at that time.

Figure 1.1 Percentage of school population at special school in 1977

4 Costs of Special School

Placement in a special school costs on average around four times as much as placement in an ordinary school and, for some pupils and some schools, considerably more. The national average school budget for each pupil in mainstream primary school is £1,500 and £2,100 for each secondary pupil compared with £7,800 for each pupil in a special school. This is easily understandable, since special schools have much more favourable pupil:teacher ratios, in addition to the use of other professionals and often specialist facilities and equipment. Thus, the decision to place a child in a special school entails the allocation of substantially increased resources to that child.

The Warnock Report of 1978

The Inquiry into Special Educational Needs, set up by the government in 1973 and chaired by Mary Warnock, reported in 1978. The Report (DES, 1978) came at a time when most Western countries were considering greater integration of pupils with handicaps into mainstream schools, and at a time of general concern for equal opportunities and human rights. The Warnock Report proposed several changes to the way in which special provision was made in the United Kingdom.

The Warnock Report suggested that it was not helpful to refer to pupils as 'handicapped', and that it was neither possible nor appropriate to draw a clear dividing line between pupils who were handicapped and those who were not. Since, the Committee asserted, handicap arises as a result of an interaction between factors within the child and factors within the child's environment, it recommended the abolition of categories of handicap and their replacement by the term 'learning difficulties' or 'special educational needs' (SEN). The Warnock Report asserted that children and young people's special educational needs occurred in a continuum of degree: thus the term 'the continuum of special needs'.

Clearly, for some pupils, assessment of disability is more straightforward than for others. Many children with special needs may be identified early on at pre-school age, and have a number of professionals already involved with them. However, there are also a large number of pupils whose difficulties emerge later and as a result of a number of difficult experiences and factors in their lives. For this reason, it was no longer considered appropriate or possible to distinguish between children who were 'handicapped' and those who were not.

The concept of SEN was introduced to include a wider range of children with difficulties than only those who were in special school, thus removing the distinction between the 'handicapped' (in special school) and those with 'educational difficulties' who were helped by 'remedial services' in mainstream schools. The continuum of special educational needs would thus range from pupils with the most profound and multiple learning difficulties at one end to those with temporary and minor learning difficulties at the other.

The Warnock Report proposed that a small minority of pupils whose needs were particularly severe and complex should be given a statement or record of SEN, thus retaining a distinction in that only those with severe, complex and long-term disabilities were to have such a statement. Another recommendation was that pupils with special educational needs should be educated in mainstream schools, with certain provisos: that such provision was in accordance with the parents' wishes, that it was compatible with the education of other children in the class, and that it permitted the efficient use of resources.

The Warnock Report estimated, by looking at various studies, that approximately 2 per cent of the school population would require statements of SEN, while up to a further 18 per cent might at some time in their school career experience learning difficulties. For most of this latter group, their difficulties would be minor, temporary and transitory, and would be likely to disappear following short-term attention in mainstream school.

Observations

Three points may be noted here.

1 The 2 per cent and 18 per cent

Although the 2 per cent and 18 per cent of pupils having special educational needs have been much quoted, there is nothing absolute about them, since they were merely estimates based on epidemiological studies of the time, and the incidence of SEN depends on many factors both within the child and within the child's environment, including the school. Some areas of the country may determine that there are more than 20 per cent of pupils experiencing learning difficulties, while others have significantly less than 20 per cent.

2 Numbers of Pupils Identified

The inclusion of a wider group of pupils as having special educational needs led, in a positive sense, to a blurring or removal of the distinction between the 'handicapped' and the 'non-handicapped'. However, on the negative side, this wider definition led to a larger number of pupils being identified and labelled. This leads to a paradox in which on the one hand there is a desire to remove categories and labels, while on the other there is a move or a need to use a new label in order to access additional resources.

3 Handicap and SEN

Although the Warnock Report abolished the previous categories of handicap, these became replaced by a new terminology such as: severe learning difficulties, emotional and behavioural difficulties, and physical and neurological impairment, which, though conferring less of a negative label, none the less serve to categorise pupils. Since the passing of the 1981 Education Act, the Department for Education (DfE) has been unable to collect statistics by category of disability, so figures concerning incidence of particular SEN are dated.

The Education Act 1981

The 1981 Education Act may be seen as the legislative embodiment of the key recommendations of the Warnock Report, As such, it constituted the integration legislation of the UK. The opening section of the 1981 Education Act defined three terms: 'special educational needs', 'learning difficulty' and 'special educational provision'. A child has 'special educational needs' if he (sic) has a learning difficulty which calls for special educational provision to be made for him. The definitions have been re-enacted without change in the Education Act 1993.

A child has a learning difficulty if —

- (a) he has a significantly greater difficulty in learning than the majority of children of his age,

- (b) he has a disability which either prevents or hinders him from making use of educational facilities of a kind generally provided in schools, within the area of the local authority concerned, for children of his age, or

- (c) he is under the age of five years and is, or would be if special educational provision were not made for him, likely to fall within paragraph (a) or (b) when over that age

(Section 156 (2) of the Education Act 1993)

'Special educational provision' means –

- (a) in relation to a child who has attained the age of two years, educational provision which is additional to, or otherwise different from, the educational provision made generally for children of his age in schools maintained by the local education authority..., and

- (b) in relation to any child under that age, educational provision of any kind

(Section 156 (4) of the Education Act 1993)

A child is not to be taken as having a learning difficulty because the language (or form of language) used at home is different from that used in school.

Observations

Three points may be noted here.

1 Special Educational Need

The Act establishes that a special educational need only exists when special educational provision is needed or called for. This is a relative matter, and depends on the provision available in the school and classroom in which the child is found. Special educational provision is defined as provision which is different from or additional to ordinary provision made generally for children of that age in the schools in that local education authority (LEA).

2 SEN Depend on Provision in Ordinary Schools

Whether a child experiences special educational needs or not is to an extent dependent on the provision made in the particular school or LEA. Since schools differ in their abilities to provide for children with different needs and LEAs differ in the extent to which they fund schools to make provision, two children with similar educational needs, in neighbouring schools or in neighbouring LEAs, could need and receive different provision under the Act. This makes it very difficult both to define and to quantify special educational needs.

3 SEN are both Relative and Interactive

In addition to being relative, children's special educational needs are interactive; children's strengths and deficits interact with their learning environment and may become more or less handicapping. An assessment of special educational needs must take into account factors within the learning environment as well as factors within the child. Two children with identical scores on tests and identical degrees of impairment may be able to function in very different ways which will result in different learning difficulties and SEN.

The Implementation of the 1981 Education Act

The 1981 Education Act was implemented in 1983 at a time when many countries of the Western world were passing legislation to promote integration of pupils with special educational needs. It was the only Act concerned with the integration of pupils with special educational needs in Western countries to be implemented without additional government finance (Wedell, 1990). Although the 1981 Act facilitated the integration of pupils with special educational needs into mainstream school, it was permissive rather than prescriptive. There were no clear incentives or financial procedures for ensuring a similar quality of provision in mainstream schools to that found in many special schools.

Following the implementation of the 1981 Education Act, most LEAs made considerable additional provision for children with special educational needs, even though they received no additional funding from central government. Many LEAs redistributed funds from other sources in order to be able to allocate more funds to SEN. This extra provision was intended both to support a larger number of pupils with special educational needs and to support pupils being integrated into mainstream schools. Moves towards integration had to be financed either from local funds or from a shift of resources from special schools to mainstream schools. In practice, there was little shift of funds, and considerable resources remained locked up in special schools while additional resources were required to support pupils in mainstream schools. In order to maintain choice between provision in special school and in mainstream school, the two systems need to be maintained, and at considerable expense. This has been criticized by the Audit Commission/HMI in their survey of provision for SEN (Audit Commission/HMI, 1992).

Additional provision by the LEA typically included peripatetic support teachers for children with learning difficulties, advisory teachers, on-site and off-site units for pupils with difficulties, individual support teachers and assistants (Goacher et al, 1988). LEA educational psychology services (EPS) expanded considerably and educational psychologists increased their involvement both in the new statutory work of formal assessment under the 1981 Education Act and in further interventions and preventative work in schools. Every LEA in the country has an E...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Original Title

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- Acknowledgements

- Part 1: Provision for Special Educational Needs

- 1 Special Needs and Provision

- 2 Identifying Special Needs

- 3 Provision by the School

- 4 Funding of Schools

- 5 Local Authority Assessments

- 6 Statements of Special Educational Needs

- Part 2: Complaints and Appeals

- 7 Local Resolution of Complaints

- 8 Complaint to the Secretary of State

- 9 Complaint to the Ombudsman

- 10 Appeal to the SEN Tribunal

- 11 Application to the High Court

- Appendices: Special Educational Needs Legislation

- 1 Sections 68 and 99 of Education Act 1944

- 2 Part of Education Act 1993

- 3 The Education (Special Educational Needs) Regulations 1994

- 4 The Education (Special Educational Needs) (Information) Regulations 1994

- 5 The Special Education Needs Tribunal Regulations 1994

- Note on law and case citation

- Abbreviations and Acronyms

- References

- Index