![]()

Chapter 1

A New Environmental Agenda for Cities?

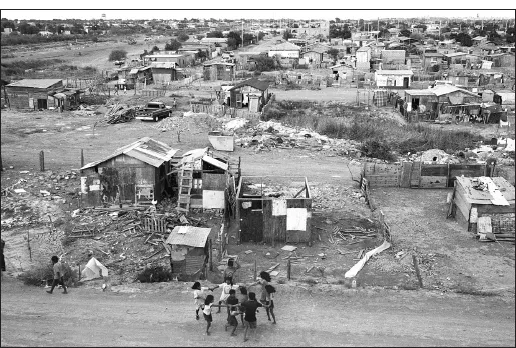

Children playing in an informal settlement in Nuevo Laredo, a rapidly growing industrial city on the Mexican border with the US

Photo © Janet Jarman, all rights reserved

INTRODUCTION

In the week when this book was being completed, landslides in Manila and in Mumbai (formerly Bombay) killed dozens of people and injured many more. In Manila, the landslide occurred at one of the city’s main rubbish dumps, when a large rain-soaked mountain of rubbish collapsed to cover a densely populated settlement of people, most of whom made a living out of waste picking. A week after the event, 205 bodies had been recovered, 2900 people had been displaced and there were still many people missing (VMSDFI 2000). In Mumbai, a hillside gave way and the informal homes perched on it were swept away. In both cities, heavy rain contributed to the landslides, however, the real causes were due to the fact that the low-income groups could find no land site that was safe and still close to income-earning opportunities and to the failure of government to ensure a safer site or to take measures to make existing sites safer.

We only learn about these disasters because they are ‘big’ enough to be reported as international news. Thousands of other urban dwellers died and tens of thousands were seriously injured in this same week in Africa, Asia and Latin America (and in every week since) from ‘smaller’ disasters that received no international media coverage.1 In most large cities and in many smaller ones in these regions, it is so common for people living in an informal settlement to be killed in an accidental fire or a flood or during a storm that it hardly makes the national press, let alone the international press.

In this same week (and in every week since), in the towns and cities in these regions, several thousand people (mostly infants and children) died of diarrhoeal diseases, several thousand more died of acute respiratory infections and several hundred died of diseases spread by insect vectors such as malaria or dengue fever. Several thousand adults died of tuberculosis or some other infectious disease. Several thousand people died of accidents on the roads, at work or within their home, with tens of thousands seriously injured. Most of the families in which an adult dies prematurely face serious economic problems because of the drop in income.

What is important about all of these deaths and injuries is first, that virtually all could have been prevented, most of them at low cost, and second that good environmental management is an important part of doing so.

ENVIRONMENTAL GOALS FOR CITIES

Cities can provide healthy, safe and stimulating environments for their inhabitants without imposing unsustainable demands on natural resources, ecosystems and global cycles. A successful city, in this sense, is one that meets multiple goals. Such goals include:

•healthy living and working environments for the inhabitants;

•water supply, provision for sanitation, rubbish collection and disposal, drains, paved roads and footpaths, and other forms of infrastructure and services that are essential for health (and important for a prosperous economic base) available to all; and

•an ecologically sustainable relationship between the demands of consumers and businesses and the resources, waste sinks and ecosystems on which they draw.

Achieving such multiple goals implies an understanding of the links between the city’s economy and built environment, the physical environment in which they are located (including soils, water resources and climate) and the biological environment (including local flora and fauna) and how these are changing. Such an understanding is essential if environmental hazards are to be minimized, and environmental capital not depleted.2 The growing realization of the environmental (and other) costs that global warming will (or may) bring adds another urgent environmental agenda to cities, but again, the above goals can be achieved with levels of greenhouse gas emissions that reduce risks.3

There are many other important environmental goals whose achievement would make city environments more pleasant, safe and valued by their inhabitants. These usually include a sense among the inhabitants that their culture and history are a valued part of the city and are reflected in its form and layout. They certainly include city environments that are more conducive to family life, child development and social interaction. It is difficult to be precise about such aspects since their preferred form will vary according to culture and climate. They will also vary within any one city – for instance well-managed public spaces and facilities become more important in densely populated areas with overcrowded housing. The precise nature of the interaction between environmental factors and human well-being also remains poorly understood. But all city environments should include a range of public or community facilities such as open spaces within or close to residential areas where young children can play and socialize, under adult supervision. All urban neighbourhoods need community centres that serve the particular needs of their inhabitants (for instance as meeting places, organization points for negotiations with external agencies, mother and child centres, places for child activities and where social events can be organized). Sites are also required in all residential areas where adolescents and adults can gather, socialize, relax, play sports and the like; these also need to be accessible, safe and maintained. Cities need parks, beaches (where these exist) and sites of natural beauty that preserve the character of a city’s natural landscape and to which all citizens have access. In hot climates, open spaces with trees can provide welcome relief from the heat, especially when combined with lakes, streams or rivers that can contribute to more comfortable micro-climates (Douglas 1983). All these sites also need adequate provision for maintenance and management.

Achieving these different goals while also responding to the needs of different groups requires a political and administrative system through which the views and priorities of citizens can influence policies and actions within the district or neighbourhood where they live and at city level. It also requires legal systems that safeguard citizens’ civil and political rights to basic services as well as rights not to face illegal and health-damaging pollution in their home, work or the wider city, and government institutions that are accountable to public scrutiny. Thus, it is about ‘good governance’ with the term governance understood to include not only the political and administrative institutions of government (and their organization and interrelationships) but also the relationships between government and civil society (McCarney 1996, Swilling 1997, Devas 1999). Good governance both at neighbourhood and city levels is critical for successful cities. It provides the means through which the inhabitants reach agreement on how to progress towards the achievement of multiple goals and how limited public resources and capacities are best used. It is also the means by which lower-income groups or other disadvantaged groups can influence policies and resource allocations. City government also has to represent the needs and priorities of its citizens in the broader context – for instance in negotiations with provincial and national governments, international agencies and businesses considering investments there.

URBAN CHANGE AND ENVIRONMENTAL PROBLEMS

Rapid urban change need not produce serious environmental problems. Cities such as Curitiba and Pôrto Alegre in Brazil have been among the world’s most rapidly growing cities in recent decades and each has much less serious environmental problems than virtually all the cities that have grown far more slowly. And as described in more detail later, some of the most serious environmental problems are found in smaller cities (or towns), including many that have not had rapidly growing populations. However, environmental problems become particularly serious where there is a rapid expansion in urban population and production with little or no consideration for the environmental implications nor for the political and institutional framework that is needed to ensure that such environmental problems are addressed. In most low- and middle-income countries, the expansion in their urban population has occurred without the needed expansion in the services and facilities that are essential to an adequate and healthy urban environment. It has usually occurred with little or no effective pollution control, and with forms of urban governance that cannot begin to meet their multiple responsibilities. It has also taken place with little regard to the environmental implications of rapid urban expansion, including the modifications to the earth’s surface (and to the local ecology), the changes wrought in the natural flows of water, and the demands made on the surrounding region for building materials as a result of the construction of buildings, roads, car-parks, industries and other components of the urban fabric (see Box 1.1).

Urban expansion without effective urban governance means that a substantial proportion of the population faces high levels of risk from natural and human-induced environmental hazards. This can be seen in most major cities in Africa, Asia and Latin America, where a significant proportion of the population lives in shelters and neighbourhoods with very inadequate provision for water and the safe disposal of solid and liquid wastes. Provision for drainage – including that to cope with storm and surface run-off – is often deficient. A large proportion of the urban population live in poor quality housing – for instance whole households live in one or two rooms in cramped, overcrowded dwellings such as tenements, cheap boarding-houses or shelters built on illegally occupied or subdivided land. Many people live on land that is subject to periodic floods, landslides or other serious hazard.

BOX 1.1 THE ENVIRONMENTAL IMPACT OF URBAN DEVELOPMENT

Urban development directly transforms large areas of the earth’s surface. Hillsides may be cut or bulldozed into new shapes, valleys and swamps may be filled with rocks and waste materials, water and minerals may be extracted from beneath the city, and regimes of soil and groundwater modified in many ways. The construction of buildings, roads and other components of the urban fabric modifies the energy, water and chemical budgets of the affected portions of the earth’s surface. As cities expand, they not only alter the earth’s surface but create new landforms (as in the case of reclaimed land).

Urban developments greatly affect the operation of the hydrological cycle, including changes in total run-off, an alteration in peak-flow characteristics and a decline in water quality. As such, they also greatly affect the processes of erosion and sedimentation. To these changes must be added the network of pipes and channels for water collection, treatment, transmission, regulation and distribution, and the culverts, gutters, drains, pipes, sewers and channels of urban waste-water disposal and stormwater drainage systems. Urbanization affects stream channels and flood-plains, often causing water to flow through cities at a high velocity.

Temperatures in urban areas are affected by many factors including the way in which the walls and roofs of buildings and the concrete or roadstone of paved areas behave in terms of high conductivity, heat capacity and the ability to reflect heat, as well as having a higher heat-storage capacity than natural soils. Also important are: the input of artificial heat generated by machinery, vehicles, heating and cooling systems; the way in which a large extent of impervious surface sheds rainwater rapidly, altering the urban moisture and heat budget; and the ejection of pollutants and dust into the urban atmosphere. The urban heat balance affects rain-producing mechanisms and the rate of snow melt over and within cities.

The creation of the city involves massive transfers of materials into the cities and within the city, and back out of the city again. These include major earth-moving activities that involve modifications to the hydrological cycle and modifications to the weight of materials on the ground surface. This redistribution of stresses in the urban area alters the natural movement of groundwater and dissolved matter within the city area. The process of building the city changes the nature of the land cover both temporarily and permanently, and induces changed relationships between the energy of falling rainwater and the amount of sediments carried into streams. This leads in turn to an increase or decrease in the sediment in the water supply to stream channels. This will affect the stability of those stream channels and the consequent pattern of downstream channel erosion.

This rearrangement of water, materials and stresses on the earth’s surface as a result of urban development and its consequences requires careful assessments, as the impacts are often felt off-site, down-valley, downstream or downwind. The terrain for urban development requires careful evaluation as legacies of past colder, warmer, wetter or drier geomorphic conditions may become unstable if they are disturbed by ill-planned earthworks. Each type of geomorphic process has special limitations for urban construction, but previous phases of urban land use may leave unstable fills, poorly drained valley floors and weakly consolidated reclaimed land. Urban sediment requires special control measures.

Source: Drawn from Douglas, Ian (1986), ‘Urban Geomorphology’ in P G Fookes and P R Vaughan (editors), A Handbook of Engineering Geomorphology, Surrey University Press (Blackie & Son), Glasgow, pp 270–283 and Douglas, Ian (1983), The Urban Environment, Edward Arnold, London.

It may also be that an increasing proportion of the urban population in Africa, Asia and Latin America is coming to live in regions or zones where the ecological underpinnings of urban development are more fragile. A considerable proportion of the rapid growth in urban population has taken place in areas that were sparsely settled only a few decades ago. In recent decades, many of the world’s most rapidly growing urban centres have been those that developed as administrative and service centres in areas of agricultural colonization or mining or logging in what were previously uninhabited or sparsely populated areas. For instance in Latin America, only in the last few decades has urban development spread to the hot and humid regions in the interior of Brazil, Bolivia, Paraguay and Venezuela, Central America and Mexico, and to the Chilean and Argentinian Patagonia region. Among the reasons why most of these regions had remained sparsely populated were the greater environmental hazards or soils that were less suited to sustained commercial exploitation (di Pace and others 1992).

Urban development without effective urban governance means that environment-related diseases and injuries cause or contribute much to disablement and premature deaths among infants, children, adolescents and adults. In many cities and in most districts in which low-income households are concentrated, environment-related diseases and injuries are the leading cause of death and illness. In many poor city districts, infants are 40–50 times more likely to die before the age of one than in Europe or North America and virtually all such deaths are environment-related. When preparing a review of the state of health in urban areas in 1990 with Sandy Cairncross (from the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine), we estimated that over 600 million urban citizens in Africa, Asia and Latin America live in ‘life and health threatening’ conditions because of the environmental problems that are evident in their shelters and neighbourhoods such as unsafe and insufficient water, overcrowded and unsafe shelters, inadequate or no sanitation, no drains and inadequate rubbish collection, unstable house sites, and the risks of flooding and other environment-r...