- 134 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Exploring Play in the Primary Classroom

About this book

First Published in 1999. This innovative series is an ideal means of supporting professional practice in the post-Dearing era, when a new focus on the quality of teaching and learning is possible. The series promotes reflexive teaching and active forms of pupil learning. Using a number of case studies this book explores the authors' fascination for the ways in which children use imaginative play to explore their ideas about the world. In pretend play and drama activities they often re-enact their experiences, coming to terms with cognitive challenges which they might not otherwise resolve.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Chapter 1

What is so Special About Play?

The main focus of this chapter is to argue for the inclusion of imaginative play within the primary curriculum. We begin by examining an episode of play in order to appreciate the processes involved. The chapter goes on to develop a model for understanding what is taking place when children play and the place of imaginative experiences in helping children to make sense of their worlds. Finally we identify some of the terms in use to describe imaginative play.

Play as a process

Children themselves have always made space for playing. At home, in the street, in playgrounds and many other settings, children can be seen behaving in ways which suggest that they have their own imaginative agendas. They appear to be imitating things around them, demonstrating the rituals of their everyday lives and pretending they have mastery of the activities they are playing out.

How any episode of play is defined has been based on insights from studies of play in its evolutionary context. Drawing upon Bateson's (1955) evidence of the range of phenomena termed play found in anthropological studies, observers agree that play is taking place because of the signals, messages, negotiations and body language which individuals use to establish that they are playing (Sutton Smith and Kelly Bryne 1984). There are sufficient clues from children's actions and vocalisations, and from the physical settings they may be in, to see the distinction between children's play and other conscious behaviours. The following case study shows the way in which one child demonstrates that she is playing and goes beyond her practical activity into a more imaginative world.

Case Study

The sandpit

Helen and Lesley, both aged four, are playing in a sandpit in an outside play area. This is one of the activities that are always available in their busy nursery. Helen is making pies and spilling and moving the sand. She has collected bricks, a spade and containers. She also moves a small oven to the edge of the sandpit. Helen's actions signal that she is engaged in playing at making sand pies, but she is also influenced by Lesley, who introduces a further imaginative element to the episode.

Figure 1.1 Making pies in the sand

Helen: French pies, loads and loads of French pies. There!

Lesley: They were burning weren't they Mum?

Helen: Yes. Leave it little girl, it hurts my back. Yes, that's how you make it. I stir it round. You put some sugar in. Leave it off - sugar - be careful you do not lose any.

You are not very young are you?

Thank you my darling.

Sugar lumps whole. I put some more sugar lumps in here OK?

It's a pain with the kids really - she brings sand indoors.

This hurts my back (filling howls).

Lesley: Mum, can we go round the shops?

Helen: Mind you don't get lost. If you get lost call me.

Oh no (sand tips over on the cooker).

Go and get over there. Sugar lumps.

(To Lesley) No love, no more.

No, in the house over there. She never listens to me.

Throughout the 20 minutes she is playing in the sand Helen is engrossed in her activity. To an onlooker she appears to be experimenting with different kinds of containers to produce her pies. This is what Piaget (1962) refers to as 'representation' or 'memory in action' and is very much at the level of the assimilation of experiential knowledge. She is also showing good coordination with her small spade and the buckets and is very concentrated on her activity. But there is much more going on in Helen's spoken language, often said very quietly and to herself. It is actually Lesley who initiates joint role play and establishes Helen as the mother. Given this cue, Helen uses her imagination to develop her role, drawing on many of the phrases she has heard from her own mother. She develops the parent role through comments such as 'It's a pain with the kids really - she brings sand indoors' as if she is talking to another adult. Helen's observations help her to try out comments she has heard and use them in the context of her own play.

So what is being demonstrated in this short episode and why is it important for Helen? Her motive is to make 'French pies', and the sand is an appropriate medium to do it. Once into role play though, she uses her imagination to create the appropriate language for talking to her daughter and also providing a commentary on her actions. She draws on her memory to use the appropriate language for this role, and for the cooking and interacting with another adult. A number of affective aspects also emerge, such as the This hurts my back' and the difficulties with children always making a mess. Vygotsky (1978) terms this type of play 'play with rules'; the rules of the parent-child relationship determining the nature of the language and the play. For example, when Helen role plays a mother she is incorporating the things her own mother might say and do. Vygotsky points out that any form of imaginary play already contains the rules of behaviour. As a mother, Helen follows the rules of maternal behaviour as she has experienced them, so that even though she is free from reality, she is also limited by the framework which Lesley has established for her.

This brief analysis leads us to offer an explanation of imaginative play as a context in which children can bring together their cognitive, social and cultural understandings. Our focus is on play as an imaginative as well as a social construct. Indeed, imagination is, as Vygotsky (1978) points out, central to what occurs when children play. Vygotsky's view is that imaginary situations are the defining characteristics of play and arise from the actions and explorations of themes. He describes play as 'a novel form of behaviour in which the child is liberated from situational constraints through his activity in an imaginary situation' (p. 96).

This emphasis on the imagination suggests the importance of children creating their own versions of their experiences and going beyond them to try out how they think something might be. Vygotsky's view of imaginative play forms the basis for our explanations and in understanding these more fully, and we now turn to notions of play in its wider context.

A social constructivist perspective

The ideas that we develop in this book are based on a social constructivist theory of learning arising from the work of Piaget (1962), Vygotsky (1978) and Bruner (1996) and developed by Donaldson (1983), Haste (1987), Edwards and Mercer (1987), Wood (1988) and Pollard (1993). Although all were writing at different times, taken together their work provides us with a perspective which encompasses the social, cognitive, cultural and affective elements of children's development. Here children are seen as actively involved in the construction of their own knowledge. They develop their learning through interactions with situations and people and through exploration and communication.

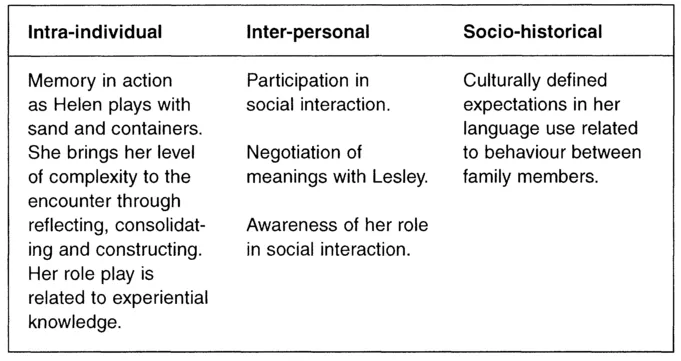

Haste (1987, p. 175) provides an account of the different domains which contribute to learning from the social constructivist viewpoint.

She specifies the:

- intra-individual domain in which children bring their own level of cognitive complexity to the encounter, assimilate experiences and construct understandings;

- inter-personal, or the domain of social interaction, where meanings are negotiated and where the cultural norms and social conventions are learned;

- socio-historical domain which draws on the wider context in which learning takes place and is defined by social and cultural practice. It also provides a resource for the rules of interaction as well as for how these rules and orders are interpreted.

We would argue that in episodes of play there are many opportunities for these domains to be brought together (see Helen and Lesley).

Figure 1.2 Play in different domains

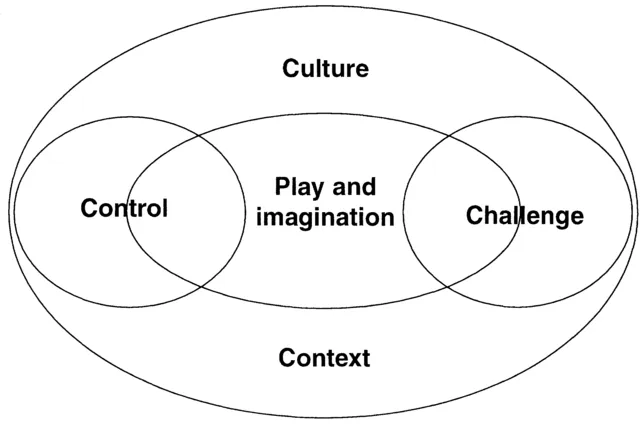

Play can provide opportunities for children to play at their own level of complexity, interact and learn to negotiate with others and draw upon the social and cultural practices which are part of their lives. The map shown in Figure 1.3 is a way of describing how this might occur.

Figure 1.3 Interactive features of play and imagination

The starting point for explaining this map is the opportunities play can provide for children to develop their imagination.

Play and imagination

In looking at the notion of play as a means of enabling children to make more sense of their lives, we wish to emphasise imagination and the emotions often related to it. Weininger (1988) conceptualises imagination as the 'thinking function' of pretend play or 'thinking through what one might do in a particular role or situation' (p. 144). In other words, when children are in a play context or have identified a theme, the way in which they interpret their theme or role requires a 'what if' question to take the ideas further. Often this occurs as children are bringing items together or playing with different objects. Their talk is almost for themselves as they move between their real and imaginative worlds in establishing the form of their play.

In the following example we see what happens when children are able to follow their own lines of thinking during an episode of free play. It shows the way their imagination can take off at different points, opening up new possibilities which enable children to flow in and out of the play according to their own needs and concerns.

Case Study

Lego models

Trevor and Peter, both aged five, have got the Lego box and set out the pieces on the carpet.

Trevor: I'll go and get a little bit first. Those bits first. Look Peter like that, then that.

Peter: Zoom my space ship here it comes.

Trevor: That how you do it Peter, is that how it goes?

Peter: Good. You put it in there.

Trevor: Then you put the two on the top.

Peter: No you can't. It isn't finished yet.

Trevor: Peter, I am going to get a little animal - an elephant in a big house.

(He pulls a box of animals towards him.)

I see a mouse on Tom and Jerry.

Yours can be a spider house.

Peter: No, I want my own. No Trevor, it looks funny. If we have it as a boat it can be a boat.

Trevor: I'll have the spider first. Why don't I put him in the little drawer? (The drawer in his model.)

Peter: Why?

Trevor: Pull it along right - this is for rescue right. Put the chicken down there. That can be yours and that can be mine. (He takes the spider round flying like a plane for a while.)

Initially the children are collaborating with one another in making the same model, but it soon becomes apparent that they each see it differently and want it to be different things. Peter then begins to develop his own model which Trevor tries to add to by bringing in small animals. This leads to a protest from Peter: 'No Trevor, it looks funny.'

Each child's imagination and feelings are an essential part of their play. Trevor is wanting approval and using imagination to make the model into different things as they add pieces to it. But he pushes Peter too far and Peter strongly protests, asserting his idea about the boat. Both boys are using the 'what if function as they add things to the model. Peter begins with a spaceship and then goes on to a boat. His 'If we have it as a boat it can be a boat' is most revealing in showing that in play you imagine something to be something else as you wish. Trevor brings in a further imaginative idea with the 'elephant' and the 'spider house'.

As they express their feelings they are also thinking about the kind of model they wish to make. Peter's 'No you can't. It isn't finished yet' and 'No, I want my own. No Trevor, it looks funny' reveals his feelings of irritation which are related to his thinking about how he wants the model to be. Initially, Peter shows empathy and appreciates Trevor's need for approval in adding pieces to the model when he says 'Good. You put it in there.'We have here what Egan (1988, p. 121) describes as our 'unique isolated consciousness' which is never the same as others, but enables us to reach out and appreciate other people's personal meanings. Thus imagination is a power which is not only intellectual but emerges as much from children's emotions as from their thinking (Egan 1988).

This episode is included to show that often when children are engaged in their free play in the classroom much more is happening than we may think. Both children in the example move in and out of thei...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- Acknowledgements

- Case Studies

- Introduction

- 1 What is so Special About Play?

- 2 Play in Classrooms: Contexts and Opportunities

- 3 How do we Find Out What Children Learn Through Play?

- 4 Scripting Play: Exploring Narratives

- 5 Play at the Core: Exploring Literacy and Numeracy

- 6 Exploring History Through Play

- 7 Constructing the Social World: From Play into Drama

- Conclusion

- Bibliography

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Exploring Play in the Primary Classroom by Gill Beardsley,Penelope Harnett in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Education & Education General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.