![]()

1

INTRODUCTION

—Content and Method

THIS BOOK IS dedicated to the view that abnormal human behavior is now, and will increasingly become, a proper subject for scientific inquiry. In order to support this contention about abnormal psychology, it is first of all necessary to describe the place of scientific inquiry in the study of normal behavior.

For students whose knowledge of science is founded upon instruction in its physical or biological branches, the notion of a “science of psychology” is not always easy to accept. Some of this reluctance to enroll psychology among the other sciences seems to be due, in part, to a misunderstanding of the nature of its actual content. Other difficulties derive from misconceptions about the nature of the methods appropriate to psychology.

So far as the content or subject matter of psychology is concerned, when we first address ourselves to the question of what it is exactly that psychology is about, we may be very dissatisfied with the answers initially offered. The questions dealt with by psychology may seem rather nebulous compared with the problems, say, of organic chemistry. The subject matter of many of the other sciences somehow seems to be much more “real.” We can see, and sometimes even handle, many of the materials with which the chemist, for example, deals. The data with which he is involved are “out there,” outside the investigator, who can, so to speak, take the substances dealt with by his science and push and pull them about. By contrast, the content of psychological inquiry, at least apparently and at first sight, may seem to be intangible and in some way, therefore, “unreal.”

This is, of course, an error, but it is one that has deep historical roots. It springs from a misconception that is perpetuated by the definitions of the word “psychology” given by almost every English dictionary. These definitions commonly state that psychology is that branch of science that deals with the nature and functions of the human mind. If we accept this kind of definition, then of course the subject matter of psychology does indeed seem to be relatively nebulous and insubstantial, because the notion of “mind,” as commonly understood, excludes the possibility of its external observation or manipulation by any set of concrete operations. What must be emphasized, however, is that this definition of psychology is one that describes the historical beginnings of the discipline rather than one that designates its contemporary interests. Most modern psychologists would prefer to define psychology as that branch of the biological-social sciences that studies behavior.

The difference between these conceptions of the nature of psychology, trivial though it may seem at first sight, is crucial to an appreciation of how abnormal behavior can be made the subject of scientific inquiry.

The traditional definition, which represents psychology as the study of the mind, assumes a form of dualism. This hypothetical split between mind and body has perhaps been best described by the philosopher Ryle in his book The Concept of Mind (1949). In terms of this kind of hypothesis, Ryle says

There is thus a polar opposition between mind and matter, an opposition which is often brought out as follows. Material objects are situated in a common field, known as “space,” and what happens to one body in one part of space is mechanically connected with what happens to other bodies in other parts of space. But mental happenings occur in insulated fields, known as “minds,” and there is, apart maybe from telepathy, no direct causal connection between what happens in one mind and what happens in another. Only through the medium of the public physical world can the mind of one person make a difference to the mind of another. The mind is its own place, and in his inner life each of us lives the life of a ghostly Robinson Crusoe. People can see, hear and jolt one another’s bodies, but they are irremediably blind and deaf to the workings of one another’s minds and inoperative upon them. (1949, p. 13)

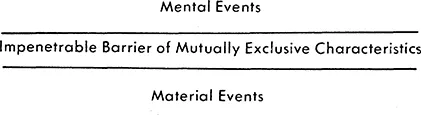

In the days in which a view of this sort was accepted, even by psychologists, there was—by definition—a complete division between psychology and the other sciences that was based on the nature of their subject matter. This acceptance of a fundamental dualism could be caricatured as the “vertical” view (see Figure 1.1) of the relation between psychology and the other sciences, in which, again by definition, there could be no common ground between material and so-called mental phenomena. An impenetrable barrier is created between mind and matter because each of these “aspects of existence” is conceived in such a way as to exclude any possibility of the interaction of one with the other. Although this duality is now accorded very little attention in general experimental psychology, it still, nevertheless, bedevils much of abnormal psychology. Such terms as “mental illness,” “mental disease,” and even “psychosomatic disorder” epitomize this dualism. It is therefore necessary to ask how the difficulties reflected in such terms may be resolved.

Fig. 1.1 Diagrammatic representation of the “vertical” view of the mind-matter dichotomy.

By the first decade of this century, experimental psychologists had come to see, and suffer from, the sterility of this kind of definition of their science. As will be emphasized later, some of the main essentials of scientific method are provided by the processes of measurement and manipulation. If, however, the content upon which these operations should be conducted has already been defined as insusceptible to these very procedures, the investigator finds himself in a very frustrating dead-end. It is probably just this irritating kind of impasse that has led, and indeed still leads, some skeptics to the belief that psychology can have little (if anything) in common with the other sciences. In other words, major and apparently insoluble difficulties arise if we accept this mental-physical division. It becomes impossible to see how one agent can act upon another if the nature of each is defined so as specifically to exclude the possibility of interaction.

This doctrine has been criticized by Ryle (1949) as involving the fallacy of the “ghost-in-the-machine.” It is a doctrine whose explicit or implicit acceptance has led some psychologists in the abnormal field to concern themselves only with the vicissitudes of the ghost, and others to concern themselves only with breakdowns in the machinery of behavior. Most modern experimental psychologists, however, have been fairly successful in bypassing this dead-end simply by redefining their area of interest. Experimental psychology is now usually held to involve the study not of “mind” but of behavior. It will be argued here that abnormal behavior can also best be studied in these same direct terms.

Two questions might immediately be raised at this point. In the first place, it might be asked how this reformulation can, in itself, help to relate psychology more usefully to other topics of scientific inquiry. In the second place, it might be asked if there are any good grounds for the belief that abnormal behavior can even hopefully be regarded as a proper subject for scientific inquiry.

To tackle the second problem first, it seems that the best answer to this question is a pragmatic one: we have to try to see. Only with the benefit—and acuity—of hindsight can we guarantee that any phenomenon whatever may be dealt with in a “scientific” fashion; we cannot be sure that any problem can profitably be made the subject of scientific inquiry until after the attempt has been made upon it. It is the purpose of this book to show that a scientific approach to the problems of abnormal behavior does indeed show both present profit and future promise.

How, then, it might be asked, can a simple redefinition of the content of psychology help to relate the subject more closely to other topics of scientific inquiry? One possible answer to this question is that it places psychology in a “horizontal” relation to the other sciences, as compared to the “vertical” relation that has already been discussed.

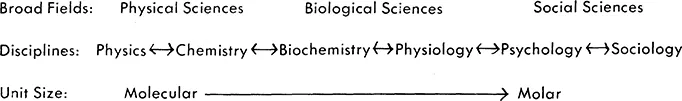

This horizontal relation is determined by the view that the various scientific disciplines may be distinguished, one from the other, in terms of the “size” of the basic unit of their discourse. This unit, which each discipline is concerned to observe, measure, and manipulate, tends to differ in magnitude from one discipline to the next, and a rough representation of the relations between the sciences—expressed in this way—is shown in Figure 1.2.

Fig. 1.2 Diagrammatic representation of the “horizontal” relation between scientific disciplines.

According to this view, psychology is bounded on its molecular side by physiology, and on the other, molar, side by sociology. Thus we move from the study of the behavior of parts of organisms, through the study of organismic behavior, to the study of the behavior of groups of organisms. The two-headed arrows between the disciplines serve to emphasize that the areas occupied by the adjacent sciences are not to be regarded as fixed, segregated, or sealed. These subdivisions, on the contrary, are bounded by permeable regions, and are, so to speak, always engaged in a kind of cultural osmosis.

It is also worth noting that the direction in which the interchange of fresh ideas and new knowledge may take place is not always from the molecular to the molar levels. Often enough, the movement is in the opposite direction, the molar sciences providing conceptions and findings that may be taken up and further explored by the more molecular sciences. Thus newly discovered physiological processes may later be formulated in the language of biochemistry, which in turn may eventually be described in terms of physical principles. At no stage in this sequence of events, however, would it be profitable to insist that discoveries at the molar end of the continuum must of necessity wait for developments at the molecular end. We must advance where we may and translate when we can.

Hebb (1958a) has provided an illuminating analogy relating to this kind of progression. He has pointed out that engineers were successfully building bridges, and in this sense developing scientific techniques relating to the larger components of bridges—such as beams and ties—long before there was any systematic knowledge of the molecular principles underlying stress and strain phenomena.

This way of conceiving the relations between the sciences also serves to protect us from the fallacious belief that the disciplines with the more molecular units somehow deal with “realer” entities and events than do the molar sciences. This fallacy is expressed in the belief that physiology, say, is a “more real” science than psychology. This is not, of course, to deny that physiology may presently be the more advanced and exact of the two disciplines; it is simply to reject the notion that all psychology is “really” a kind of physiology—a contention that would make no more and no less sense than would the claim that all physiology is “really” a kind of biochemistry. Each domain, in fact, is entitled to deal in its own terms with its own subject matter, although this may overlap with the content of adjacent, or even more distant, disciplines.

The boundaries between disciplines, then, are not hard and fast, or watertight, limits; they involve, rather, zones or areas where the concerns of the sciences overlap. They are, in fact, more like areas of climatic influence than like national frontiers. For this reason it would be misleading to try to be too exact about the precise size of the basic, defining unit with which any particular scientist deals. Roughly speaking, the physiologist, on the one hand, is commonly interested in unlearned bodily events; the psychologist, on the other hand, is usually concerned with learned organismic activity. The difference between them might therefore be held to lie in the transition from the unconditioned to the conditioned reflex; the interests of many workers will, however, coincide when such a limiting size of unit is defined. There is, in other words, no need for any discipline or any scientist to “stake a claim” on a particular piece of “territory” since all areas will contain a variety of problems that may be tackled in many different ways.

It is also essential to note that our horizontal, two-dimensional figure gives a very much oversimplified picture of the relations between the disciplines. A more realistic description might be given only by a multidimensional, nonlinear scheme, which would show, quite rightly, that the relations between psychology and the other disciplines are complex and complicated. Even the simple horizontal view, however, is certainly not as misleading as the vertical conception of the relation of psychology to the other sciences. The former contains within itself the fruitful possibility of interaction, the latter only the sterile certainty of separation.

So much, for the moment, for the definition of the subject matter of psychology. The qualifying term “abnormal” reflects the fact that one branch of the discipline concerns itself mainly with the study of deviant behavior. Some of the kinds of behavior with which it deals will be considered later in terms of actual examples.

As the quotation from Claude Bernard (1957) at the beginning of this text states, there seem to be two main aspects to scientific method, both of which may be discerned in the activities of psychologists as scientists. First, there are those studies that are principally concerned with the description and measurement of behavioral characteristics. Second, there are those studies that are more concerned with changing or manipulating behavior. It must be emphasized, of course, that these are not by any means hard and fast categories; in many studies the two procedures of measurement and manipulation must inform and complement one another. It would be impossible to engage profitably in any attempt to change behavior unless it were also feasible to define, describe, and, if possible, accurately measure those characteristics of behavior that we intend to change. Important differences can, however, be traced between those kinds of study in psychology that are mainly concerned with observing and measuring and those that are mainly concerned with producing changes in behavior.

One of the first attempts at the former kind of study began in the field of educational-developmental psychology. In these investigations the behavior observed by the psychologist is usually produced by his subjects in response to a fixed set of standard stimuli, which often take the form of items in some kind of test. The familiar intelligence test provides a well-known example. The notion that underlies this kind of testing is, of course, that individual differences exist in the behavioral as well as in the physical sphere of human organization. Thus, while we can talk about some people being heavier than others, we may also talk about some people being brighter than others. An intelligence test, however, is not a kind of psychic light-meter that can give an unequivocal estimate of the absolute amount of such “brightness”; it is, rather, away of conveniently comparing a given individual with a particular reference group so that we can determine his status on the test in relation to the performance of others in the group. The hope is that his group status, as defined by the test results, will be correlated with some other, usually more broadly defined, kinds of performance that it would be inconvenient or impossible to examine directly.

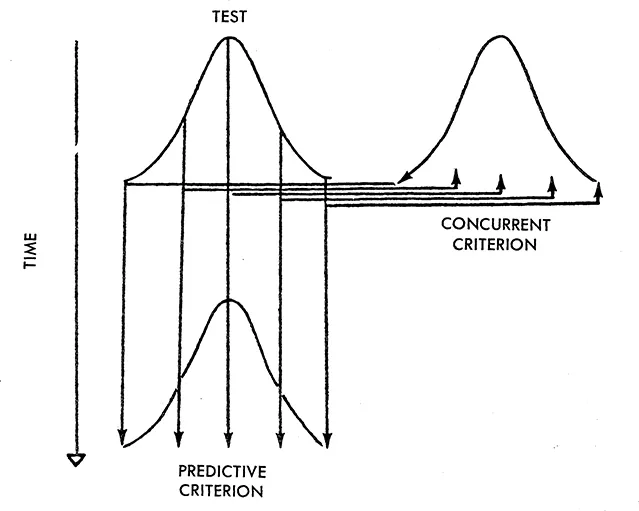

Test behavior, in fact, is useful only insofar as it enables us to predict the relative status that an individual will maintain in his performance in a criterion situation. We may try to establish the propriety of this kind of inference in a number of ways; for example, through the estimation of concurrent validity or through the estimation of predictive validity. These kinds of validation procedures may be represented as in Figure 1.3, which, however, shows only the special case of perfect correlation. This diagram illustrates the fact that the inferences that can be drawn from tests are valid to the degree to which their results are mirrored in criterion situations.

In the fields in which such testing was first developed, these situations were usually educational or vocational. Some intelligence tests, for example, are validated in terms of their ability to predict later educational achievement, and others relate more immediately and directly to current social adjustment or to vocational attainment. This kind of test may also, therefore, find some direct application in the study of abnormal behavior; for example, in the determination of intellectual defect. A very low test score may be, within limits, predictive of poor future educational and poor social adjustment.

Fig. 1.3 Illustration of two types of validation procedure.

A more ambitious and perhaps an even more common use of psychological tests in the field of abnormal behavior, ho...