![]()

Part I

Phonetics, phonology, and morphology

![]()

1

Arabic phonology

Eiman Mustafawi

1 Introduction

In this chapter, a general description and discussion of the phonology of Arabic is presented. First, the sound system of Modern Standard Arabic (MSA) is briefly discussed and compared to the sound system of Classical Arabic (CA) as described by CA grammarians. Differences, or possible differences, between the two are highlighted. The phonemic inventory of MSA is then compared to those of the other Arabic spoken varieties, conventionally classified into six main dialect groups from East to West: Gulf Arabic (GA), Iraqi Arabic (IA), Levantine Arabic (LA), Yemeni Arabic (YA), Egyptian Arabic (EA), and Maghrebi Arabic (MA). Comparisons among these varieties are drawn in terms of sound system, syllable structure, and stress patterns. Some sound alternations in different dialects are analyzed within an Obligatory Contour Principle (OCP)–driven framework. Additionally, processes such as assimilation, affrication, lenition, and pharyngealization are discussed. Occasionally, reference is made to specific dialects within the six major groups, and new data are presented from less-studied dialects.

2 Historical background

The first systematic study of the phonology of Arabic was undertaken by Al-Khaliil and then elaborated on by his student Sibawayh in the 8th century. Except for some contributions from Ibn Jinni, later works by CA grammarians were basically a repetition of the findings of Sibawayh. Compared to the extensive discussions of syntax in his major book Al-Kitaab, the sections that addressed phonology were limited in number and scope. However, this book included accurate description of individual sounds in the segmental inventory of the language, including cases of variation, in addition to discussions of some of the widespread phenomena at the time, such as Imaala ‘front vowel raising’ (Hellmuth 2013) and what is currently called “pharyngealization”. Nothing new was added for centuries until European orientalists became interested in the language, probably because of its relation to Hebrew and possibly in part for missionary purposes (Versteegh 1997). The work of Brame (1970) brought Arabic to the attention of modern linguistic theory, and after that data from Arabic motivated new developments in the field or was used to test new theories as they emerged.

3 Critical issues and topics

3.1 Phonemic inventory

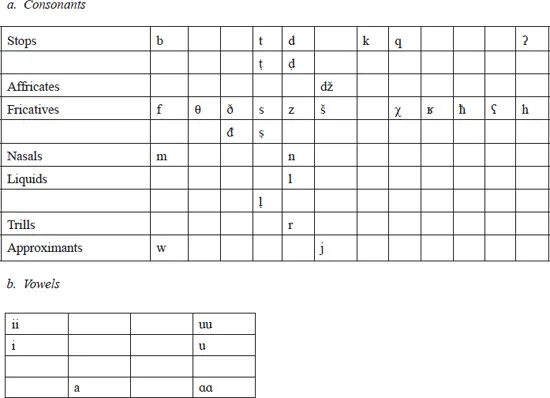

Like most Semitic languages, Arabic has a rich consonantal inventory but a limited vocalic system (Watson 2002; Holes 2004). Unlike other Semitic languages, however, Arabic has kept most of the pharyngeal and emphatic consonants believed to have existed in Proto-Semitic (Hijazi n.d., pp. 139–140; Kaye 1997, p. 194). The phonemic inventory of MSA consists of 34 phonemes, six of which are vowels. These are given in Table 1.1. More consonants and vowels would normally surface at the phonetic level. While MSA is considered a slightly simplified version of CA in terms of its lexicon and syntax, it is reasonable to believe that the differences between MSA and CA extend to phonology, particularly, to its phonemic inventory.

3.2 MSA and CA

In this subsection, I discuss some of the differences between the phonemic inventories of CA and MSA. The first of these differences concerns the sound that is orthographically represented by the grapheme (ض). In MSA, this letter (letter and grapheme will be used interchangeably) is pronounced as an emphatic voiced dental stop, phonetically [ḍ], which is the emphatic counterpart of [d]. However, Sibawayh (Al-Kitaab IV 1999, p. 572), the medieval grammarian of the 8th century, describes this grapheme as representing a voiced emphatic fricative whose place of articulation lies between the teeth and the palate, and he identifies it as having no non-emphatic counterpart. While no one can tell with certainty what the actual pronunciation of this grapheme was in CA, a few attempts have been made by different scholars to identify its phonetic value. For an extensive discussion of this sound, the reader is referred to Cantineau (1953, p. 79; 1960, p. 55), Kaye (1997), and Al-Osaybi‘i (1992, pp. 114–119). Except for the latter, these scholars attribute a lateral or lateralized place of articulation to the grapheme (ض) based on the descriptions found in Sibawayh and other medieval sources (e.g., Ibn Jinni 1993). Furthermore, some of the old texts indicate that (ض) was originally a fricative with a point of articulation similar to that of [dž, š] (Al-Khalil, cited in Versteegh 1997, p. 23; Ibn Ya‘ish, cited in Osaybi‘i 1992, p. 31; and in Anis 1992, p. 130). Based on a similarity metric introduced in Frisch et al. (2004) and the statistical study of Mrayati (1987), the distributional pattern of (ض) is consistent with a coronal emphatic having the features [-anterior, +continuant, +voice]1 (Mustafawi 2006, p. 101).

Table 1.1 The phonemic inventory of MSA

The second difference between the phonemic inventories of MSA and CA is related to the sound that is represented orthographically as (ط). This letter is pronounced as a voiceless dental emphatic stop in MSA, i.e. [ṭ]. It is however described as a voiced dental emphatic stop in Sibawayh (ibid), clearly stated to be the emphatic counterpart of (د), the latter having the phonetic quality of [d]. This gives CA (ط) the phonetic representation [ḍ]. Sibawayh, however, indicates that this letter has a marginal pronunciation that is “similar to (ت)/[t]” (IV, p. 572), which seems to be identical or very similar to the pronunciation of (ط) in MSA ([ṭ]). For further elaboration, the reader is referred to Cantineau (1960), Hijazi (n.d., p. 300), Anis (1992, p. 62), Al-Osaybi’i (1992, p. 70).

The third difference between the two systems is the pronunciation of the grapheme (ق). It is pronounced as a voiceless uvular stop in MSA, that is [q], but described as a voiced2 uvular stop in Sibawayh, giving it the phonetic value of [G] in CA (Cantineau 1950, p. xxvi; Bergsträsser 1983, pp. 162 and 187; Anis 1992, pp. 85 and 208). Other than these three differences, the phonemes of MSA and CA are believed to be identical.

3.3 MSA and modern Arabic varieties3

Although it is widely assumed that Modern Arabic Varieties (MAVs) must have descended from CA (for example, Al-Salih 1989, p. 360), a comparative study between some of the old Arabic dialects (as described by CA grammarians) and MAVs point to the contrary. In fact, there is ample evidence (mainly phonological) indicating that MAVs descend from old Arabic varieties that had existed side by side with CA since the early stages of the language (Rabin 1978; Freeman n.d.; Mahadin 1989; Anis 1995; Wafi 2000; Mustafawi 2006, among others).4 For a discussion of this topic, the reader is referred to Freeman (n.d.) and Owens (2006).

MAVs are generally classified as being descendent of sedentary or nomadic origins, and this classification accounts for most of the observed similarities and differences among these varieties. Nomadic dialects are on one hand in general more conservative and more similar to CA/MSA than are sedentary dialects (see Holes 2004 and references therein). Sedentary dialects on the other hand show features that reflect influences from other languages that co-existed with Arabic in the major cities of the Arab World (mainly in Egypt, the Levant, and North Africa), namely Aramaic, Nabataean, Coptic, and Berber.5 Also, sedentary varieties were subject to more innovation than were nomadic varieties.

Additionally, MAVs are grouped into five, sometimes six, major dialect clusters (if YA is considered as a separate group)6 based on geography and linguistic features (Versteegh 1997; Holes 2004, among others). These are: GA,7 IA, YA, here mainly San’ani, all following nomadic patterns, LA, represented here by the varieties of the major cities in the Levant such as Amman, Beirut, and Damascus, EA, represented by the dialect of Cairo,8 and MA, represented here by the varieties of major cities in Morocco, Algeria, Libya, and Tunisia, all of which follow sedentary patterns. Variation may exist within each dialect group and even within each country with respect to certain phonological phenomena. Hijazi Arabic in Saudi Arabia, for example, follows the patterns of sedentary varieties, while the rest of the country is generally categorized with GA.9 Also, LA includes dialects that exhibit variation in pronunciation and intonation (Bassiouney 2009); and the same is true for MA.

Except for GA and YA, the sedentary/nomadic classification cross-cuts all the other major dialect groups. That is, within a single regional group, certain sectors of the population may have a sedentary-like dialect, and other groups within the same region or country may have a nomadic type of dialect. However, it is worth mentioning that there may also be fairly distinct sedentary dialects within one region. Moreover, Arabic dialects are classified as being Eastern or Western. The Maghrebi dialect group stands alone as the Western dialect group, the other dialects mentioned above being Eastern. The latter include the varieties of Chad, Nigeria, and Sudan (Kaye and Rosenhouse 1997, p. 265).

With respect to the phonemes of the language, the main differences between MSA and MAVs are outlined in sections 3.3.1 through 3.3.6. Additionally, some phonemes were introduced in certain dialects through borrowings that turned into established loanwords in the respective dialects. For example, /v/, /ž/, /ẓ/ are added to the phonemic inventory of EA (Watson 2002); /ẓ/ to LA (Holes 2004); /g/ to Tunisian Arabic (Maamouri 1967); /tš/ to Moroccan Arabic (Heath 1997); /p/, /tš/ to IA (Rahim 1980); and only /tš/ to Jordanian Arabic (Alghazo 1987) and GA (Mustafawi 2006).10

3.3.1 Interdental fricatives /θ/, /ð/, and /đ...