![]()

1 The young gifted child: setting the context

General background

Recognising and nurturing young children's abilities and interests is an exciting challenge. It is exciting because younger children are often hungry for knowledge; they are curious and are more forthcoming with imaginative ideas. They have unique personalities and specific abilities which need to be identified so that we can do everything in our power to help these young people to make the most of their special strengths and realise their full potential. They may show all-round ability or demonstrate special strengths or aptitudes in academic areas such as English, mathematics and science. Some may, in addition, demonstrate special behavioural characteristics such as organisational ability and leadership skills from a very young age. The challenge for the teacher is not only to recognise the multiple talents of the child, but also to think of ways of acknowledging these talents and, of course, to then apply the most effective strategies to nurture all their talents. By doing so, we are more likely to support young children to develop their self-esteem and confidence. They will also be encouraged to take pleasure in learning, thereby contributing to their development into well-rounded personalities.

I have always wondered whether we feel an extra sense of responsibility to do our best for younger children because they are more vulnerable and perhaps more dependent on adults than older children. Without proper support younger children's curiosity could be stifled, their 'play and exploration' time could be curtailed for what they may feel is considered more 'serious' and 'proper' work, and they may feel that using their imagination is unimportant and not worthwhile. Yet curiosity, play and imagination are the essence of a creative mind which is what we are always striving to encourage.

The issues I have raised are by no means limited to the education of younger children. Why are they particularly important when considering able younger children? First, habits are formed very early in life. Attitudes and styles of learning as well as self-perceptions developed during the first years of schooling will most certainly influence future learning. In addition, gaps in their knowledge and understanding could lead to disinterest in school and lower achievement.

Research evidence tells us that external stimulation can enhance learning potential of children in the early years of their lives. Studies (Vaughn, et al. 1991; Fowler et al. 1995, quoted in Porter 1999) suggest that provision of enrichment activities and early interventions help to raise achievement levels of younger children significantly. As children are receptive to new ideas and cognitive restructuring at a greater speed in the first few years of their lives, time and effort given to them will be worthwhile. This is applicable to all children, but is particularly important in the case of children who may not, for all sorts of reasons, receive the stimulation they need in their homes. I will discuss the issue of the importance of early identification and enrichment further in Chapter 2.

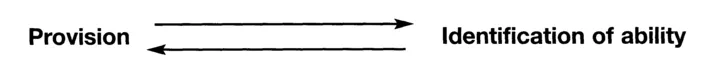

There is an ongoing debate among educators of young children whether children should be labelled 'gifted' before they are seven or eight years old. This debate does not pose a problem for the approach I have adopted for writing this book because the model I am using is based on a two-way process, as shown below, when dealing with children who show high ability in one or more areas.

Whatever terminology we use to describe children who demonstrate higher ability, what matters most is what we provide for them in the classroom. For example, in the two-way process of 'provision and identification' the emphasis is on maximising 'opportunities' for children so that they will show their potential talents. Observation and identification of special strengths, 'gifts' or 'talents' will then enable teachers to make appropriate provision based on their observations.

My reference to 'gifted' children refers to observed and recorded special abilities which should help adults to build up profiles of the children. If a list of academically 'gifted' children's names is required at any stage, the profile should assist in composing that list.

The national scene on educating the gifted and talented

In England and Wales, the past few years have witnessed the introduction of several initiatives by the government to support the education of the gifted and talented. There has also been a number of significant developments in aspects relating to general (not specifically relating to gifted children) provision for children in the early years. At the time of writing this book, discussions on introducing new extension tests - introducing a level 3* in academic subjects at the end of Key Stage 1 - are taking place. The purpose of these tests is to assess children's in-depth knowledge in subjects so that these can be acknowledged earlier in their school life.

Before we consider national developments on gifted education, it will be useful for you to reflect for a moment and write down how you would define giftedness. During in-service sessions I often ask teachers to put their hands up if they thought they were 'gifted'. Only one or two out of about forty participants ever put their hands up. When we discuss why they did not feel they were 'gifted', the reason which often emerges is that they have difficulty interpreting what I mean by being 'gifted'. 'Do you mean exceptionally good at everything or at some things?' is one question they often ask. It is interesting to note that many more teachers say that they are particularly 'good at some things, but not at everything' and if that definition was used, many more would feel they were 'gifted'. As discussed elsewhere (Koshy and Casey 1997a), based on over 600 teachers' evaluations of the effectiveness of our inservice courses on gifted education, teachers find the discussions of various terminology used to refer to higher ability children to be one of the most useful aspects of the course. What usually emerges after the discussions is that we really are referring to children who show higher ability in all or some areas of the curriculum. This working definition is useful for what we do in our classrooms.

According to the DfES definition, the term 'gifted' refers to those with high ability or potential in academic subjects, and 'talented' refers to those with high ability or potential in the expressive or creative arts or sport. This is the terminology which is also used for OFSTED inspections.

Concerns about the lack of provision for gifted children have been voiced by many for at least three decades. Her Majesty's Inspectorate asserted (HMI 1992) that the needs of the very able were not being met in many schools and that such pupils were not sufficiently challenged. Around the same time Alexander et al.(1992) pointed out that there was 'obsessive fear' in some schools about being deemed 'elitist' and as a consequence 'the needs of some of our most able have quite simply not been met'. And - for those who felt uneasy about focusing on the needs of the able - HMI Mackintosh (Ofsted 1994, p. 13) had this to say:

There is very clear evidence that focusing sharply on what the most able can achieve raises the expectations generally, because essentially it involves consideration of the organisation and management of teaching and learning.

Many Ofsted inspection reports also highlighted the need for providing more intellectual challenge in classroom activities. So what is on offer for the gifted and talented?

In 1997 (DfEE) the government announced in the White Paper entitled Excellence in Schools:

We plan to develop a strategy for the early identification and support of particularly able and talented children. We want every school and local education authority to plan how it will help gifted and talented children.

An inquiry by the House of Commons Select Committee (1999) highlighted the problems many schools experience in offering an appropriate curriculum for the gifted, and declared that this aspect of education needed attention. The main areas of concern were the lack of high expectations from gifted children and the need for schools and teachers to have a better understanding of ways in which provision can be improved. As a result, in March 1999, the government launched the 'Excellence in Cities' (DfEE 1999) initiative for raising the achievement of pupils in inner-city areas. As part of this, all participating secondary and primary schools were required to:

- Identify their 5 to 10 per cent 'gifted and talented' pupils. The percentage refers to the schools' intake, not the whole school population. In practice, the most able within a school would be referred to as the 'gifted and talented' pupils.

- Appoint a coordinator responsible for the education of these pupils.

- Implement a distinct teaching and learning programme for the gifted and talented.

At the present time, funding is provided only for schools in local education authorities within the Excellence in Cities areas, but other forms of support have been offered to all schools. These include support publications, from the DfES, for teaching numeracy and literacy (DfES 2000a), and materials from the QCA, entitled 'Teaching Gifted and Talented Pupils in Mathematics and English at Key stage 1 and 2' (See Chapter 7 for resources). World-class tests are available for gifted and talented pupils in mathematics and problem-solving at the ages of 9 and 13 from QCA. These may be taken by children at an earlier age if they feel ready for them.

Two years after the start of a national drive for improving educational opportunities for gifted children, where are we now? One of the concerns highlighted in the research carried out at Brunei University (Thomas et al. 1996) looking at provision for gifted children, using a national sample, was teachers' lack of understanding of strategies for classroom provision. An evaluation of 'gifted and talented' provision carried out by Ofsted (2001) acknowledges that a promising start has been made. As the following points among the recommendations for improvement are particularly relevant to the context of this book, they are summarised below:

- Schools would benefit more generally from greater help on assessment and forms of teaching which support higher achievement at an earlier stage.

- The identification of gifted and talented pupils has presented difficulties for schools. To date, methods of identification have generally been rudimentary and have not yet solved the problem of recognising latent high ability, particularly among pupils who are underachieving generally.

- There is a need for greater engagement of parents and pupils.

- Schools need to establish a secure basis for improving mainstream teaching.

Two aspects emerge from what has been presented in the previous section: (1) schools need to think about effective procedures for the identification of gifted and talented children, and (2) they need to devise strategies for effective classroom provision. To help me to set up some expectations for writing this book, I carried out a survey of schools in six LEAs - three from the Excellence in Cities areas and three others - as a needs analysis exercise which formed part of the work of Brunel University's able children's education centre. The following useful points emerged from the survey.

- Many nursery and infant teachers felt they have not been provided with adequate internal or external support with aspects of identification or provision.

- Only three out of 12 infant teachers and none of the four nursery teachers in schools where there were school policies for 'gifted and talented' children said they knew the contents of those policies.

- Fourteen out of the 18 infant and nursery teachers who took part in the survey felt there was very little coverage of issues relating to provision for younger children at both short and longer in-service courses.

- There was a serious shortage of books and resources directly targeting issues relating to the education of younger gifted and talented children.

Although the size of the sample used in this survey was small it did highlight the need for writing this book. I also recollect what one DfES 'gifted and talented' officer, Richard Smith, pointed out to me, during a discussion I had with him prior to leading a seminar on improving provision for Key Stage 1 children, at the Gifted and Talented Stand...