eBook - ePub

Trauma-Informed Practices for Early Childhood Educators

Relationship-Based Approaches that Support Healing and Build Resilience in Young Children

This is a test

- 248 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Trauma-Informed Practices for Early Childhood Educators

Relationship-Based Approaches that Support Healing and Build Resilience in Young Children

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

Trauma-Informed Practices for Early Childhood Educators guides child care providers and early educators working with infants, toddlers, preschoolers, and early elementary aged children to understand trauma as well as its impact on young children's brains, behavior, learning, and development. The book introduces a range of trauma-informed teaching and family engagement strategies that readers can use in their early childhood programs to create strength-based environments that support children's health, healing, and resiliency. Supervisors and coaches will learn a range of powerful trauma-informed practices that they can use to support workforce development and enhance their quality improvement initiatives.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Trauma-Informed Practices for Early Childhood Educators by Julie Nicholson, Linda Perez, Julie Kurtz in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Education & Early Childhood Education. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Understanding the Neurobiology of Trauma

What Role Do Caregivers Play in Facilitating Early Brain Development?

Key Topics Covered

• Brainstem, limbic brain, neo-cortex

• Arousal states

• The impact of stress on the developing brain

• Defining trauma and the different types of trauma

• The impact of trauma on young children’s development and capacity to learn

• Attunement, co-regulation, and mirror neurons

• Neuro-plasticity, resiliency, and healing

Neurobiology 101: Brain Development in the Earliest Years

Brain development begins when a baby is growing in the womb. Neurons are the foundational elements of a baby’s brain growth. Neurogenesis, or the process of growing new neurons, is a process that occurs throughout an individual’s lifetime, although neural growth is most active during the first two trimesters of pregnancy. An estimated 86 billion neurons form the basic structure of a baby’s brain at birth (Azeveo et al., 2009; Herculano-Houzel, 2009). At birth, every neuron in a baby’s cerebral cortex has approximately 2,500 synapses (the gaps between neurons), by 2 years of age the number closely approximates an average adult’s brain, and by the time a child reaches their third birthday, every neuron has approximately 15,000 synapses, an amount that is about twice the number in a typical adult’s brain (Conkbayier, 2017; Rogers, 2011). This is why the early childhood years are so critical. Synaptic growth—where neurons are connected to other neurons—is strongly influenced by environmental conditions and a direct result of the various experiences a child has whether developmentally supportive or traumatic and impairing.

When Does Brain Development Start?

Brain development begins when a baby is growing in the womb. Brain growth is significant and extremely fast while a baby is growing in utero, which is why the prenatal environment is so critical. Many factors can have a profound impact on a vulnerable and developing fetal brain, particularly maternal health. Such factors include diet/nutrition, exercise, substance abuse, mental health challenges (depression, anxiety, etc.), exposure to environmental toxins, and most significantly, experiences of prolonged traumatic stress. Young children’s healthy brain development starts with the health and well-being of their mothers. This is why supporting maternal health before, during, and after pregnancy is a critical foundation for healthy child development.

Through healthy and caring relationships, play, exploration of their environment, and responsive communication where adults help children feel safe and belonging in their families and communities, children develop healthy synaptic connections that become a neurobiological foundation supporting their future academic learning and social-emotional health. Similarly, early traumatic experiences can interrupt normal synaptic growth from occurring, leading a young child’s brain to develop differently with negative outcomes that can last a lifetime without proper intervention. This is why neural plasticity—or the brain’s ability to alter its structure and function in response to internal bodily changes or external environmental changes—is most rapid during a child’s first few years of life when their brains are most influenced by environmental factors. As Conkbayier (2017) explains:

Neural connections grow and are strengthened in response to [environmental] experiences, be they positive or negative. Repetition of experiences leads to neurons creating pathways in different parts of the brain, based on experiences. Perry (2001) tells us that experience, good and bad, literally becomes the neuroarcheology of the individual’s brain.

(p. 14)

What Is Pruning?

A process called pruning is essential for young children’s healthy brain growth. During the pruning process, synaptic connections that are used in a child’s brain are strengthened and those that are not used are eliminated. As children develop relationships and have experiences, the neural connections that have the most “usage”—the neurons that fire most often in the child’s brain—will be strengthened and maintained and those that are used least often will be “pruned away” making room for new neural growth to take place. This is often referred to as “Use It or Lose It” (Perry et al., 1995).

The process of pruning is most active during infancy (especially just after birth) and throughout the adolescent years. This is why the quality of early interactions and experiences can have such significant and long-term effects for children. If, for example, a child does not have caring attuned relationships with adults in their earliest years, the neural pathways that support emotions and emotional regulation can be significantly impaired. Additionally, if a child is not exposed to rich vocabulary or provided with many opportunities to actively explore their environment, the healthy neural networks they need for future academic learning may be lost instead of developed and strengthened through the pruning process.

Young children’s caregivers have a tremendously important role in guiding their healthy brain development. It is important that early childhood teachers understand how neural structures are created and form the building blocks of children’s development and their potential to learn. They have a tremendous responsibility to support young children’s brain development. As Wolfe (2007) explains, they must understand that every child they care for, “represents a virtual explosion of dendritic growth. [Early childhood educators] are so fortunate to be in a profession where [they] can create learning opportunities to best support young children’s development and their biological wiring” (cited in Rushton, 2011, p. 92).

The Hierarchical Nature of Children’s Brain Development

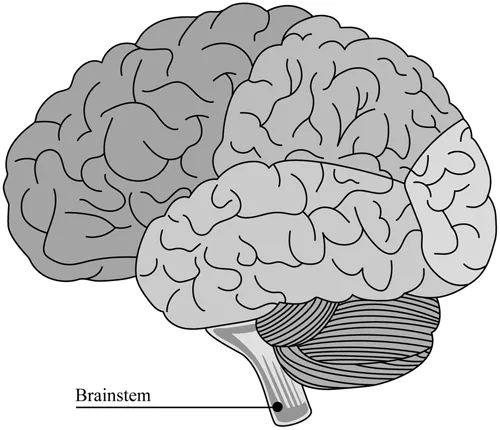

The process of neural growth occurs sequentially from the “bottom up” (Perry et al., 1995). The first areas of the brain to fully develop are the brainstem and midbrain (the midbrain is part of the brainstem), as they are responsible for the bodily functions necessary for life, which are called the autonomic functions (e.g., breathing, sleeping, blood pressure). The last regions of the brain to fully develop are the limbic system, involved in regulating emotions, and then the cortex, involved in language, abstract thought, reasoning, and problem-solving. Because of the sequential nature of neural growth, if one “layer” of the brain’s development is interrupted and/or impaired, the subsequent parts of the brain will also not develop properly. For example, if trauma damages the healthy development of a child’s brainstem, the child’s limbic system and cortex will not function optimally, which may show up as delays or impairments with language development or difficulty with social-emotional skills or cognitive processing (Figure 1.1).

Figure 1.1 Brainstem.

Courtney Vickery

The Brainstem (Primitive or “Reptilian” Brain). The first part of the human brain to develop in the womb is the brainstem, whose function is similar to the brain of reptiles. Thus, the nickname, reptilian brain. The primitive part of the brain is responsible for the FLIGHT, FIGHT, and FREEZE response humans have when they perceive danger. We all need this part of our brain to mobilize an emergency or survival response in situations of crisis. If a child puts their hand on a hot stove, their brainstem gives them the ability to react quickly and remove their hand so that they do not sustain burns. If an adult driver gets cut off on the freeway, it is their brainstem that quickly reacts and makes them swerve quickly away from a potentially fatal situation. This part of the brain is referred to as the “alarm center” or “smoke detector” (van der Kolk, 2014) and it continually scans the environment for red flags and sends messages that lead us to perceive whether we are safe or should mobilize to prepare for danger.

A Window Into Your Brainstem At Work …

Imagine you are driving on the freeway and out of nowhere, someone cuts you off. Your reptile brain kicks into high gear and serves a life-saving function of helping you immediately mobilize your energy to focus quickly to avoid the car swerving into your lane. Your brain sends signals to increase your heart rate and blood flow to your extremities shutting down all other bodily functions so that you can quickly save your life by escaping the potential danger.

Or, if your supervisor sends you a very direct and extensive email about your performance deficits, this could also immediately trigger a reaction that sends you into your reptile brain. With your heart racing, you quickly respond by pounding out an email solely authored by either the fight, flight, or freeze reptile brainstem.

FIGHT: You immediately email back to your supervisor a defensive, attacking, and reactive response to prove them wrong.

FLIGHT: Another response while in this part of your brain is the need to run away. You “decide” right then to state that you are sick and will send it in the evening so you will not have to deal with any confrontation.

FREEZE: When in freeze mode, you find ways to completely disconnect and avoid the situation. Unhealthy freeze strategies for an adult may be binge eating with food, abusing drugs, alcohol, or other similar strategies that help you numb out and disconnect from the world.

Perhaps you have been working with a child where you just set a firm limit. If the child yells “I hate you and I hope you die,” the adult caregiver may be triggered emotionally and default directly to their reptile brain. If you have a reptilian brain reaction toward the child, you would use punishment or other punitive strategies such as criticism, threats, or shaming.

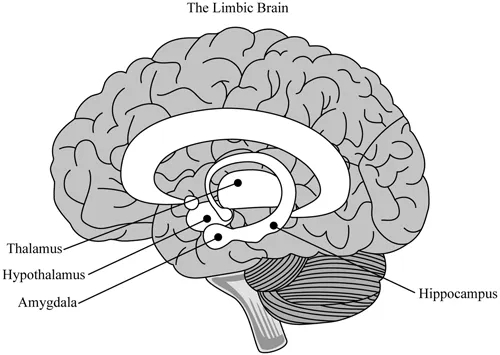

The reptile part of your brain is life saving and helps you in an emergency such as a fire, an unexpected car swerving in your lane, a tornado, or even day to day stressors. You need this part of your brain to mobilize your personal physical resources for survival. However, if you habitually default to your reptile brain during normal day to day stressors, then you will be more reactive and punitive, thus causing more harm to children impacted by trauma (Figure 1.2).

Figure 1.2 Limbic system.

Courtney Vickery

The Limbic Brain (Emotional or Mammalian Brain). We share this part of our brain with mammals. The functionality of the mammalian brain differentiates us from our more primitive reptilian brainstem. It generates our feelings, emotional intensity of feelings, and creates our desire for attachment, significance, and belonging. Attachments, emotions, and emotional regulation of our behavior are all generated and expressed through this part of the limbic brain. Young babies are born with what is called “an experience-dependent limbic system,” which means they need lots of repeated positive emotional, social, and cognitive interactions to support the development of a healthy limbic system (Conkbayir, 2017, p. 43; Twardosz, 2012). The limbic brain includes several different elements:

• Thalamus. Among the roles of the thalamus is the process of receiving sensory information and through synaptic connections sharing it with the neo-cortex (discussed below).

• Hypothalamus. The hypothalamus is responsible for autonomic functions including our perception of thirst and hunger, maintenance of our body temperature, and sleep. It also controls the release of hormones from the pituitary gland including the secretion of adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH), which stimulates the production of cortisol and oxytocin. In this way, the hypothalamus creates a bridge between the endocrine system and the nervous system.

• Amygdala. The amygdala controls our survival responses and allows us to r...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half-Title

- Series

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- Introduction

- 1 Understanding the Neurobiology of Trauma

- 2 Foundations of Trauma-Informed Practice for Early Childhood Education

- 3 Trauma-Sensitive Early Childhood Programs

- 4 Case Study: Infant and Mother Living in a Homeless Shelter

- 5 Case Study: Toddler with a History of Neglect and Three Foster Home Placements

- 6 Case Study: Preschooler with an Undocumented Father who Suddenly Disappears Due to Deportation

- 7 Case Study: First Grader who Recently Witnessed a Drive-by Shooting While Playing at School

- 8 The Importance of Self-Care in TIP Work: Taking Care of Yourself in Order to Prevent Burnout, Compassion Fatigue, and Secondary Traumatic Stress

- Conclusion

- Resources on Trauma and Trauma-Informed Practices

- References

- Appendices