- 768 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

International Marketing

About this book

The third edition of an established text, this book provides comprehensive treatment of international marketing issues and includes expanded coverage of Eastern Europe and the Pacific Rim.

New for this edition are the expanded use of mini cases within the text to illustrate the latest developments in marketing, together with expanded coverage of: South East Asia and the Pacific Rim, Central and Eastern Europe, Globalization, Culture, Financial aspects of marketing.

Included throughout are self-assessment and discussion questions, key terms, references and bibliography.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

CHAPTER 1

Internationalization: a necessity not a luxury, but does corporate behaviour reflect it?

The concept of advantage

The starting point oegrns with international trade, something which has been practised by many civilizations over many thousands of years. A visit to any museum will reveal some of the artefacts of ancient daily life which were traded across vast distances, as with the Roman treasures still being found in Britain today. These ancient goods represent products what today we might call standardized products. The urns, bowls, vases and pottery ware, which are all identified as indisputably Roman, conformed to a certain specification of manufacture and were then transported.

The Roman garrisons in Britain in 44AD were captive markets for products known to the Romans. Their situation was similar to that of the US army divisions in the Second World War which simply by taking overseas with them certain products or more importantly brands, which US soldiers regarded as being from ‘home’, created a multinational product and presence for products such as Coca-Cola.

Today, we have moved one step further from Ricardo’s Theory of Comparative Advantage to the point where in some sections of industrial activity, the competition which exists is global rather than national, as in computers or automobiles where the sourcing of components and assemblies is another multinational activity. Size and the well-understood principle of economics of scale have given rise to highly dynamic competition. The critical mass that a company requires to cover breakeven costs is also forever increasing, partly because of technological push, partly also because of market-driven forces which create demand for new or improved products. The so-called ‘Green Revolution’, which has swept Europe and North America, has given rise to new car specifications and to engines able to bum unleaded fuel; and to soaps, detergents and products generally that are biodegradable and will not pollute the environment. These products in turn offer new advantages which are passed on to the consumer. However, if the customer does not value these new product advantages, which have been created at a cost that has been passed on to the customer, then the customer will avoid this particular brand in future in favour of a cheaper, more basic variant. In this case the manufacturer will only add to overhead costs and have lost certain of his customers.

With the passage of time, it is noticeable how these changes sweep through different countries almost simultaneously. Countries at approximately the same level of economic advancement may be expected to have environmentally aware consumers able and willing to do something about caring for the environment involving changing their behaviour, perhaps changing their product purchases, even if it does mean finding an extra few pence outlay on a shopping bill. This differential can be labelled ‘conscience money’, and the psychological benefit of doing something positive for the environment may well compensate those consumers for this additional outlay. The problem is in establishing the critical threshold as to how much people are prepared to pay. It does create marketing segmentation opportunities for companies to explore across nations, so spreading the costs of product development further, and across more than one market. The Green Revolution is a good example of social change that has led to segmentation strategies for specially formulated, environmentally friendly products.

Where is the nation state

Absolute advantage, which is traced back to Adam Smith, stated that trade would take place between two nations, each having something the other wanted to buy, but could not produce for itself. The instances of absolute advantage were few and so the Ricardo Theory of Comparative Advantage then took hold. This said that it made sense still to trade when there was no absolute advantage; prices may be similar to those at which you could produce yourself. However, what the Theory of Comparative Advantage then went on to say was that this offered the nation the opportunity for specialization in a certain sphere of activity. Depending on a nation’s factor endowment, it could choose to focus and specialize In a particular area in which it then could create an advantage. Minerals and raw materials might give an advantage but cheap labour was only a very short-term advantage.

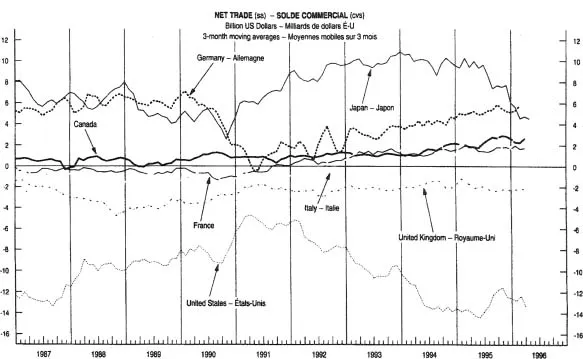

Source: OECD (1996) Main Economic Indicators, Paris, August

Figure 1. 1 Foreign trade

Yet to Porter, the key to whether a nation is competitive in an industry is not whether it trades, but whether it has a combination of trade and investment that reflects advantages and skills that have been created at home. Porter (1990) sees classical economic theory as deficient in explaining trade and investment in advanced nations for three reasons:

1.Globalizationwhich decoupies the firm from the factor endowment of its home nation.

2.Factor poolsof many nations reaching a certain comparability. Comparative advantage in terms of factor costs is only temporary.

3.Technology.Where labour content is too high, automation can be introduced. Similarly with raw materials, if these prove to be scarce, new synthetic ones can be created.

Porter (1990) then argues for the sources of advantage to be ‘relentlessly broadened and upgraded’. Where home customers are demanding, and seek quality and sophistication, this in turn forces the firm to improve; but, where home customers are merely accepting of variable quality offerings, this then can lace the firm at a disadvantage in international markets. Demanding customers and strong competition move companies away from dependence on the lowest common denominator,

In the same way, many new products today have arisen from technologies related to mature industries. Examples of internationally competitive-related industries include Denmark in dairy products and brewing, giving rise to industrial enzymes; Switzerland with its strength in pharmaceuticals, giving rise to flavourings; and the UK with a strength in engines, giving rise to a related industry in lubricants and ‘anti-knock’preparations.

Governments are generally eager to help national companies but Porter does not find this governmental help to have been an advantage. Instead, it is better to have firms which are self- sustaining and able to compete independently.

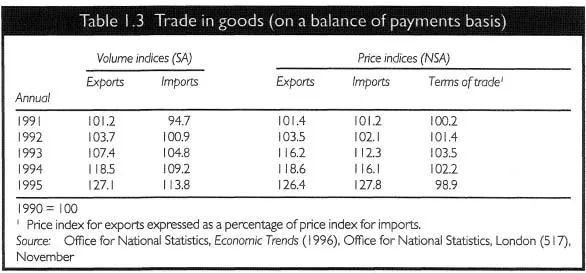

The UK share of world trade has decreased from around 25 per cent, at the end of the nineteenth century to approximately 6.5 per cent of global exports and imports today. Nevertheless, the UK still earns a greater, although declining, percentage of its GDP from exports than many other major industrial countries. At the same time the need toimport raw materials plus half its food needs, underlines Britains dependency on foreign trade. Table 1.3 shows that if we focus particularly on the export sector, we find that exports indexed over 1990 levels have been increasing in both volume and value.

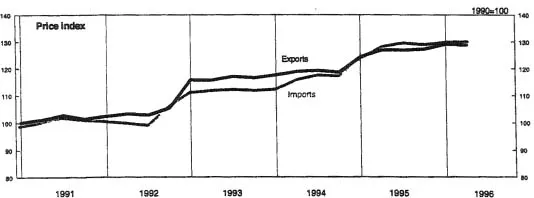

It is interesting to note, from Table 1.3, that imports are now down and overtaken by exports first in volume then in price. This is emphasized in the last column, ‘Terms of Trade’, and is depicted in Figure 1.2.

Britain has had a balance of trade deficit on manufactured goods since 1983. It is worth bearing this point in mind also when we come to discuss the product life cycle and its applications to international marketing.

Analysing national competitiveness

An analysis of international competitiveness is the annual IMD World Competitiveness Report which uses a questionnaire survey assessing 326 criteria divided into ten categories and mailed to 10, 000 selected executives in the 34 countries covered by the report. Eight of the criteria are:

1.domestic economy

2.internationalization

3.government

4.finance

5.infrastructure

6.management

7.science and technology

8.people.

Source: Ofice for National Statistics, Economic Trends (1996), Office for National Statistics, London

Figure 1.2 UK visible trade: unit values of exports and imports

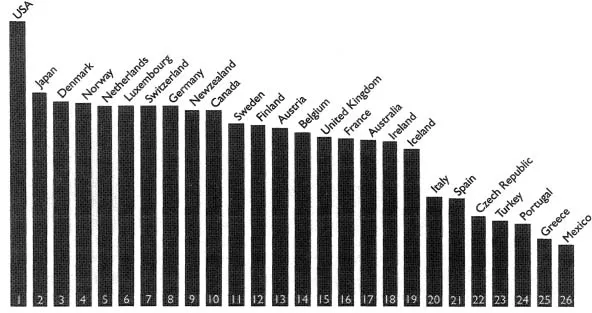

IMD maintain that a nation’s competitiveness can only be tested in the international marketplace. Some nations act as host to foreign direct investment, others are investors. However the means by which value added is created is behind the IMD survey. They adopt a matrix approach to try to present a balanced picture of mi economy and to represent where investment is taking place. Nations are compared within the groups, OECD and non-OECD. Interestingly, Poland joined the OECD in June 1996 and so is categorized here as non-OECD but is ranked alongside other non-OECD countries. It is not possible therefore just to transfer the scores into the other grouping.

Source: The World Competitiveness Yearbook (1996) IMDMlodd Economic Forum, Lausanne, Switzerland

Figure 1.3 The OECD scoreboard: developed nations

Exhibit 1.1 Surveys agree to disagree

A rift between co-authors of the annual World Competitiveness Report has led to a second international survey on wealth creation in less than 3 week-with radically different results.

While the United States topped the charts of the Lausanne-based International Institute for Management Development, the country slips to fourth place when judged by the Geneva-based World Economic Forum.

Germany, ranked 10th by the IMD earlier this week, plummets to 22nd place on the latest list compiled by the Forum.

Canada was listed I 2th by the IMD but is eighth on the Forum’s report.

Singapore, Hong Kong and New Zealand, small, open economies with relatively small governments and low tax rates, steal the top three rankings in the Forum’s report.

Macha Levinson, a director of the World Economic Forum, calls it a reflection of the growing debate over just what competitiveness is.

‘There is no way this is meant to be a definitive answer to the whole question of competitiveness, There is a very heated discussion going on right now. Our methodology will evolve, ’she said.

The World Competitiveness Report has been published for 17 years by the World Economic Forum, an independent, non-profit organization. Half of the reports have been compiled jointly with the IMD.

The two organizations parted ways last year after a dispute over research methods.

The Forum says its latest report offers a new way of judging competitiveness, which it def...

Table of contents

- Cover

- International marketing

- Books in the series

- Title page

- Copyright page

- Contents

- foreward

- introduction

- preface

- Acknowledgements

- 1 internationalization: a necessity not a luxury, but does corporate behaviour reflect it?

- 2 Environmental market scanning: the SLEPT and C factors

- 3 Exporting-not just for the small business

- 4 Market entry modes: strategic considerations of direct vs. indirect involvement

- 5 International product policy considerations

- 6 Pricing, credit and terms of doing business

- 7 Strategic international logistical and distribution decisions

- 8 Promotion within the foreign market

- 9 International marketing planning: reviewing, appraising and implementing

- 10 Marketing in Europe

- 11 Marketing in the Pacific Rim

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access International Marketing by Stanley Paliwoda,Michael Thomas in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Business & Business generale. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.