- 157 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

First Published in 1998. Baseline assessment will be compulsory from September 1998. Enshrined in the Education Act 1997, and subject to cross party support, baseline assessment has high popularity - at least in principle. This book reviews these different elements and purposes, and their implications for practice. The authors review the educational, psychological and psychometric factors which are relevant to developing baseline assessment and consider the socio-political context in which these initiatives are occurring.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Chapter 1

Baseline assessment: political background to educational change

Introduction

The frantic pace of educational change in the UK over the past decade can be traced back to the 1988 Education Reform Act, which in its preamble stated that the Act was to:

promote the spiritual, moral, cultural, mental, and physical development of pupils and of society; and prepare pupils for the opportunities, responsibilities and experiences of adult life

There would be few who would disagree with such praiseworthy aims, but many who would question whether the structures set up by the Act would help schools to achieve them.

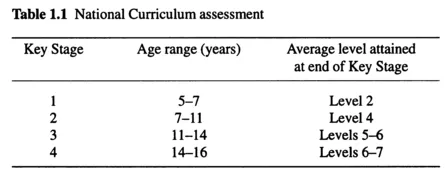

A central part of the legislation was the setting up of a National Curriculum and its associated framework of assessment. The structure of the National Curriculum described each subject area in terms of ten levels of attainment stating the knowledge and skills that defined each level. The years of compulsory education were divided into four key stages, and set levels of attainment that should be reached by the average pupil at the end of each key stage (see Table 1.1).

It also laid out a statutory framework for assessment at the end of each key stage, together with the requirement that results on an individual pupil basis must be given to parents, and results on an aggregated school and LEA basis must be published at the end of Key Stages 2 and 3, together with GCSE and A level results for secondary schools. In 1994 a review of the National Curriculum (Dearing 1994) recommended that assessment at the end of Key Stage 4 should not use the levels of the National Curriculum, but simply use GCSE grades.

The major stated aims were to raise educational standards, to improve the education of all children, and to increase the accountability of schools to the client groups they serve - defined as parents and industry, but not pupils or local communities. A further aim was to introduce market economics into education. There should be an element of choice for consumers, leading to competition between schools. This was thought to provide a healthy stimulus to improve quality, to the benefit of pupils, parents and the national economy. As in any period of rapid change, different parts of the political and educational system tried to influence the outcomes of these reforms, and the struggle between ministers, civil servants and educational professionals during the implementation of these reforms is documented by Graham and Tytler (1993).

Other reforms to curb the power of local government and reduce its role in education led to the setting up of grant maintained schools totally independent of the LEA, the local management of schools and delegation of both finance and decision making away from LEAs to individual schools. Changes to the composition of governing bodies, and extending their powers further reduced the role of the LEA. Alongside these changes were mechanisms to make schools more accountable to the communities they served - publishing of league tables of results of public examinations and end of key stage National Curriculum assessments, the regular inspection of schools by OFSTED and the publication of the resulting reports. A further thrust was the declared intention of central government that educational standards should be improved, and that schools would be held publicly accountable for their failures.

Educational standards

The concerns about educational standards seem to be perennial, and were as much part of earlier Labour administrations as they were of the Tory government between 1979 and 1997. The Labour Prime Minister James Callaghan in 1976 made a speech in Oxford where he declared that he wanted to start a great debate on education, and at the root of his concerns was a fear of declining educational standards, possibly sparked off by the moves to comprehensive schools at secondary level during the 1960s and early 1970s.

It is worth noting that the evidence to support these views of declining standards is tenuous, with ever increasing percentages of each age cohort obtaining five or more grade A-C at GCSE, and greater percentages going on to higher education as the annual statistics from the Department for Education and Employment show. The 1990-91 panic about falling reading standards in primary schools was set off by educational psychologists reporting results of authority-wide reading tests from a small number of LEAs. Subsequent investigations by HMI (1990) and NFER (Cato and Whetton 1991) could not find evidence to support these alarmist views, other than a small decrement in performance that appeared to coincide with the introduction of the National Curriculum. This led to a further dimension to the debate on falling standards, with comparisons being made with other countries world wide, particularly with the countries of the Pacific Rim, to demonstrate a relative decline in the levels of basic numeracy and literacy of UK pupils.

Richards (1997) notes that primary education has long been the subject of myth-making, and summarises the current negative myths as 'children are not being taught to read, write and calculate properly, they while away the day on trivial pursuits, and their standards of attainments are lower than their predecessors of twenty, thirty or forty years ago'. He is especially critical of the way OFSTED reports make use of their own data to paint a gloomy picture of primary education that is very difficult to substantiate, even from those data.

The new Labour administration which came to power in May 1997 seems to be pursuing similar policies to the previous government, based on the belief that standards of education are generally unsatisfactory in state schools. The priority given to education in the general election campaign was followed up two months later by the White Paper Excellence in Schools published in July 1997. An important belief in how school improvement can be brought about seems to be that

given the right balance of pressure and support, standards rise fastest where schools take responsibility for their own improvement.

(SCAA 1997a, p.1)

The School Curriculum and Assessment Authority (SCAA) had already indicated the importance of education in the early years if pupils were to make satisfactory progress in National Curriculum subjects during Key Stage 1. Desirable Outcomes for Children's Learning on Entering Compulsory Education (SCAA 1996a) set out a pre-school curriculum focusing on six areas of learning: personal and social development, language and literacy, mathematics, knowledge and understanding of the world, physical development and creative development. The document describes in some detail how desirable outcomes in each of these areas contributes to National Curriculum targets in Key Stage 1. The major emphasis for the function of nursery education is on the preparation of pre-school children for the National Curriculum, rather than a balanced consideration of the child developmental perspective. The role of nursery education to support National Curriculum achievements is clearly expressed in Excellence in Schools (DfEE 1997a), which on page 17 states

The 'outcomes' provide national standards for early years education ... and are designed to provide a robust first step towards the National Curriculum and we shall re-examine them at the same time as we review the National Curriculum.

It would be hard to give a clearer statement of views on the function of nursery education.

Whilst the Desirable Outcomes document does not have a statutory basis, its publication coincided with legislation on the introduction of vouchers for pre-school education. As a condition of validation for the receipt of vouchers, institutions were required to publish a statement of the education provided. Confirmation of validation was based on a judgement, through inspection, about the extent to which the quality of provision is appropriate to the desirable outcomes in each area of learning. Although nursery vouchers have now been withdrawn, inspection of nursery provision based on the Desirable Outcomes document will continue, and SCAA has published guidance on good practice (SCAA 1997e).

National Curriculum assessment

A major theme in the development of the National Curriculum has been the central role of assessment, and the way results have been used for a variety of purposes. There are three major purposes of assessment: firstly to inform teachers and pupils of the progress being made and to decide the next steps in learning (formative); secondly for the certification of individual students to provide a publicly recognised standard that the student has achieved at the end of a particular stage of education (summative); and finally to provide information serving the public accountability of schools and teachers for their successes and failures (evaluative). This last function is the one that has received the most publicity in recent years with the publication of league tables of how successful schools are in terms of National Curriculum Key Stage 2, GCSE and A level results. The difficulties of making sense of this information is dealt with at length in Chapter 4.

So far, National Curriculum Key Stage 1 results have not formed part of published league tables, and there are still many uncertainties about the reliability and validity of all end of key stage National Curriculum assessments, as no information on their technical quality has been made available, despite the claim in Excellence in Schools that 'we now have sound, consistent, national measures of pupil achievement for each school at each key stage of the National Curriculum' (p.25). The thinking of the new Labour Government on the use of assessment information is clear. They have expressed the view that each school and LEA should set annual targets for improvement. A consultation paper Target Setting and Benchmarking in Schools was produced by SCAA in September 1997. There is the belief that parents and others should have raw results on attainments, and that this should be supplemented by a measure of how much progress individual pupils have made during each key stage. At the end of Key Stages 2 and 3 the results at the end of the previous key stage can be used to measure progress, but this is not possible for Key Stage 1 unless baseline assessment is introduced for all five year old pupils as they enter infant school.

Purposes of baseline assessment

Baseline assessment is now enshrined in law. The Education Act 1997 gave the starting date for compulsory baseline assessment of five year olds as September 1998, and despite the change of government, the Labour administration are committed to this timetable. They have declared that they want this to be the first form of assessment introduced on the basis of partnership with teachers, and not confrontation with them, and that it has a crucial role in the measurement of added-value:

As baseline assessment at age 5 is progressively introduced, it will be possible to measure any pupil's progress through his or her school career, and also compare that pupil with any other individual or group, whether locally or nationally.

(DfEE 1997a, p.25)

The historical roots of baseline assessment are in the early identification of special educational needs (SEN), going back more than 20 years. Before then, earlier systems, such as Child Guidance, attempted to provide a service which helped identify the developmental difficulties of children and young people, and then offer an intervention aimed at amelioration (Sampson 1980). Epidemiological studies pointed to the benefits of the systematic examination of whole cohorts of children to identify those with educational difficulties (Rutter et al. 1970), but these investigations were often later in children's educational careers, with an obvious delay before intervention could take place to help those with difficulties. In an effort to overcome these difficulties, a group of educational psychologists, education advisers and headteachers became interested in trying to identify children before they developed educational problems, that is, those 'at risk'. A number of psychologists developed approaches to aid the early identification of children who may be at risk of developing educational difficulties (Wolfendale and Bryans 1979, Lindsay 1981, Pearson and Quinn 1986).

Wolfendale (1993) notes that in the early 1990s baseline assessment was linked with a new set of purposes - a way of helping to impose practice in terms of early record keeping and profiling of children's attainments as they enter infant school to help curriculum planning, provide appropriate curriculum differentiation and ensure progression for each child. At the same time the Record of Achievement movement had been very successful at Secondary school level in broadening the base of assessment, and giving much greater importance both to self-assessment skills and to personal and social development as well as academic attainment (e.g. Broadfoot et al. 1989). These new approaches to assessment were taken up by primary schools, and schemes such as All About Me (Wolfendale 1990) and the Sheffield Primary Record of Achievement and Experience (Sheffield LEA 1993) were developed, to include the transition from home to infant school.

Baseline assessment was also linked to the National Curriculum, and its associated assessment procedures, that at Key Stages 2 and 3 had led to school league tables. Concern at the unfairness of average raw scores being used to judge school effectiveness, with little or no contextual information such as socio-economic factors of the catchment area or rate of progress made during the key stage, had led to the notion of 'value-added'. It was thought that the results at the end of the previous National Curriculum key stage could be used to calculate the value-added component of how effectively the school had taught the child. But what of Key Stage 1? Some headteachers, particularly of separate infant schools, or nursery and infant schools, had become interested in assessing developmental levels when children first entered school, and using this as a baseline against which progress could be measured at the end of Key Stage 1.

There were clear tensions between the broader base of the Records of Achievement approach to early assessment, and the school curriculum based approach of the National Curriculum, and it was difficult to see how these tensions could be resolved (Desforges 1991).

Lindsay (1998) considers the many purposes of baseline assessment, and groups them into two major categories, each with several different purposes.

Child focus

Early identification of children with SEN. If we are to identify individual children with SEN, all children must be screened, followed by a further assessment phase for all those identified as possibly at risk on the screening measure. Many teachers are concerned about the dangers of early labelling five-year-old pupils in what they see as a negative way, but recognise the benefits if it leads to positive outcomes for the children identified.

Early identification of children's SEN. To identify the specific difficulties and resulting educational needs of particular children, there is a need for a more detailed examination of the child's profile using either, or both, normative and criterion referenced measures. Such assessments may be carried out by other support workers as well as the class teacher or Special Educational Needs Coordinator (SENCO).

Monitoring all children's progress. There is now a better understanding of the need to monitor the progress of all children, not just those with special educational needs, to ensure prog...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- Preface

- 1 Baseline assessment: political background to educational change

- 2 Child development

- 3 Screening for children with special educational needs

- 4 Value-added

- 5 Technical quality of baseline assessment

- 6 Development of the Infant Index and Baseline-plus

- 7 Early identification and the Code of Practice

- 8 Interventions

- 9 Looking to the future

- References

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Baseline Assessment by Geoff Lindsay,Martin Desforges in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Education & Education General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.