This is a test

- 262 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

This illustrated survey examines what it was actually like to live with plague and the threat of plague in late-medieval and early modern England.; Colin Platt's books include "The English Medieval Town", "Medieval England: A Social History and Archaeology from the Conquest to 1600" and "The Architecture of Medieval Britain: A Social History" which won the Wolfson Prize for 1990. This book is intended for undergraduate/6th form courses on medieval England, option courses on demography, medicine, family and social focus. The "black death" and population decline is central to A-level syllabuses on this period.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access King Death by Colin Platt in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & World History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

CHAPTER ONE

Mortalities

What does it matter how many people died in the Black Death? I shall argue in this book that it matters a great deal. But there is truth also in the view that “so much of the population was surplus by the fourteenth century that the early famines [of 1315–17] and the mid-century pestilences [of 1348–9] were more purgative than toxic”.1 And the remarkable resilience of English institutions, both during and after the Black Death, would certainly support such a conclusion.2 By 1361, when the plague returned to England on the first of many visits, that resilience was already under challenge. “The beginning of the plague was in 1350 minus one”, records the well-known contemporary inscription on the church tower at Ashwell (Hertfordshire). Then in larger letters below, cut soon after the second outbreak – the pestis puerorum or mortalité des enfants of 1361 – had carried off the new-born children of the survivors, the carver’s despair is palpable: “wretched, fierce, violent [pestilence] … [only] the dregs of the populace live to tell the tale.”3 And that was just the beginning of over three centuries of deadly visitations, until bubonic plague inexplicably disappeared.4

Among the most vivid accounts of the Black Death’s origins and symptoms are those of its earliest survivors. Giovanni Boccaccio, author of The Decameron, wrote one of the best of them. Boccaccio witnessed the plague in Florence in the spring and summer of 1348:

Some say [he begins] that it descended upon the human race through the influence of the heavenly bodies, others that it was a punishment signifying God’s righteous anger at our iniquitous way of life. But whatever its cause, it had originated some years earlier in the East, where it had claimed countless lives before it unhappily spread westward, growing in strength as it swept relentlessly on from one place to the next … Its earliest symptom, in men and women alike, was the appearance of certain swellings [buboes] in the groin or the armpit, some of which were egg-shaped whilst others were roughly the size of the common apple. Sometimes the swellings were large, sometimes not so large, and they were referred to by the populace as gavoccioli. From the two areas already mentioned, this deadly gavocciolo would begin to spread, and within a short time it would appear at random all over the body. Later on, the symptoms of the disease changed, and many people began to find dark blotches and bruises on their arms, thighs, and other parts of the body, sometimes large and few in number, at other times tiny and closely spaced. These, to anyone unfortunate enough to contract them, were just as infallible a sign that he would die as the gavocciolo had been earlier, and as indeed it still was … Few of those who caught it ever recovered, and in most cases death occurred within three days from the appearance of the symptoms we have described, some people dying more rapidly than others, the majority without any fever or other complications.5

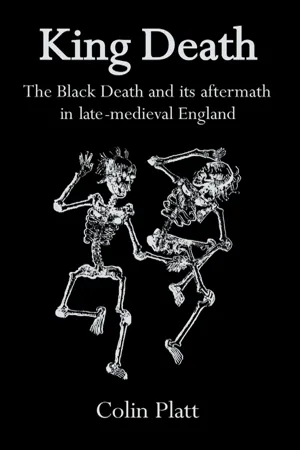

1. “Its earliest sympton … was the appearance of certain swellings in the groin or the armpit, some of which were egg-shaped while others were roughly the size of the common apple.” In this woodcut, from a late-fifteenth-century Nuremberg treatise on bubonic plague, a doctor is shown lancing one of the buboes Boccaccio describes. The Wellcome Centre Medical Photographic Library.

2. A manuscript talisman against the plague (contra pestilentia) from a fifteenth-century English leech book. The Wellcome Centre Medical Photographic Library.

From March until July, wrote a fellow Florentine, Marchionne di Coppo Stefani, “all the citizens did little else except to carry dead bodies to be buried … At every church they dug deep pits down to the water level; and thus those who were poor who died during the night were bundled up quickly and thrown into the pit. In the morning when a large number of bodies were found in the pit, they took some earth and shovelled it down on top of them; and later others were placed on top of them and then another layer of earth, just as one makes lasagne with layers of pasta and cheese.6

“It is reliably thought,” reported Boccaccio, “that over a hundred thousand human lives were extinguished within the walls of the city of Florence.”7 It was an over-estimate, of course: among the first of many. But what worried Boccaccio and his contemporaries, in any event, was as much the manner of those deaths as their sum. “Bodies were here, there and everywhere,” writes Boccaccio, so that every customary ceremony was set aside. “There were no tears or candles or mourners to honour the dead; in fact, no more respect was accorded to dead people than would nowadays be shown towards dead goats.”8 Fifty-two thousand are said to have died in Siena that same summer, and another 28,000 in its suburbs. And while figures like these are obvious fictions, there is no mistaking the personal anguish they recall:

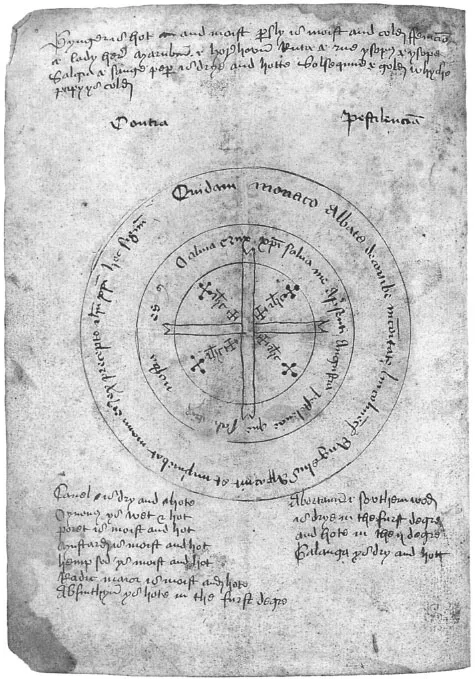

3. Plague victims are buried at Tournai (Flanders) in the autumn of 1349: a miniature illustrating the contemporary Chronicle of Abbot Gilles li Muisis – “After the feast of St John [29 August] the mortality began in the parish of St Piat in Merdenchon Street, and later it began in other parishes, so that every day the dead were carrried into churches: now 5, now 10, now 15. And in the church of St Brice, sometimes 20 or 30. And in all the parishes the priests, the parish clerks and the grave diggers earned their fees by tolling the passing bells by day and night, in the morning and in the evening; and thus everyone in the city, men and women alike, began to be afraid; and no one knew what to do.” (Rosemary Horrox (trans. and ed.), The Black Death (Manchester, Manchester University Press, 1994), pp. 51–2). The Wellcome Centre Medical Photographic Library.

Father abandoned child; wife, husband; one brother, another … And none could be found to bury the dead for money or friendship … And in many places in Siena great pits were dug and piled deep with the multitude of dead … And I, Agnolo di Tura, called the Fat, buried my five children with my own hands.9

It was not much later, in the autumn of 1348, that the Black Death visited England. “It began first in India,” wrote Henry Knighton, its most reliable English chronicler, “then in Tarsus, then it reached the Saracens and finally the Christians and Jews … Then the most lamentable plague penetrated the coast through Southampton and came to Bristol, and virtually the whole town was wiped out. It was as if sudden death had marked them down beforehand, for few lay sick for more than two or three days, or even for half a day. Cruel death took just two days to burst out all over the town. At [Knighton’s own] Leicester, in the little parish of St Leonard, more than 380 died; in the parish of Holy Cross more than 400; in the parish of St Margaret 700; and a great multitude in every parish.”10

These are Mickey Mouse numbers again. But Knighton, while writing some 40 years later, was a conscientious and discriminating historian.11 And the picture he paints of England’s post-plague desolation carries more conviction than his statistics:

After the aforesaid pestilence many buildings of all sizes in every city fell into total ruin for want of inhabitants. Likewise, many villages and hamlets were deserted, with no house remaining in them, because everyone who had lived there was dead, and indeed many of these villages were never inhabited again. In the following winter there was such a lack of workers in all areas of activity that it was thought that there had hardly ever been such a shortage before; for a man’s farm animals and other livestock wandered about without a shepherd and all his possessions were left unguarded. And as a result all essentials were so expensive that something which had previously cost 1d was now worth 4d or 5d.12

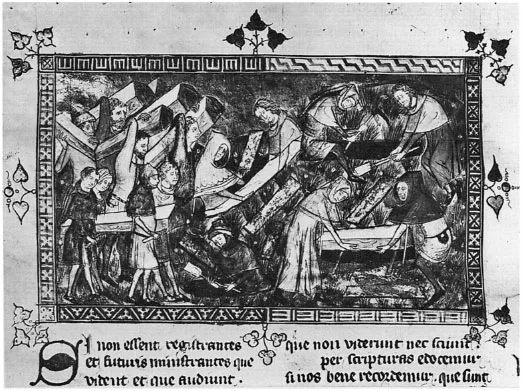

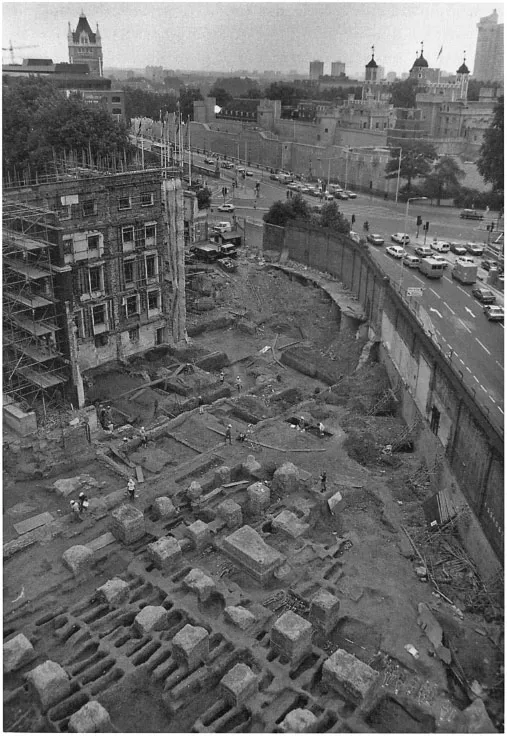

4. A Black Death cemetery under excavation at East Smithfield, just south of the Tower of London. To the south again was the site of the Cistercian abbey of St Mary Graces, founded in 1350 by Edward III in part fulfilment of an earlier vow but also as a memorial to his late confessor, Archbishop Thomas Bradwardine, who died of the plague within weeks of his elevation to Canterbury. While many of these London plague victims were given coffin burials, there were at least two mass graves at East Smithfield – and probably many more – in which the dead (carefully laid) were stacked up to five bodies deep (Duncan Hawkins, “The Black Death and the new London cemeteries of 1348”, Antiquity 64, 1990, pp. 637–42). Museum of London Archaeology Service.

Knighton, a canon of Leicester Abbey, died in 1396. And it was in that same year that Thomas Burton, of Meaux Abbey (East Yorkshire), completed the first draft of his Chronica Monasterii de Melsa. Burton, more even than Knighton, had the instincts of a professional historian. “No one,” he promises, “who finds anything in what follows which he did not know before, should think that I invented it; he must rest assured that I have only included what I have found written in other works or in a variety of documents, or have heard from reliable witnesses, or have myself seen.”13 Accordingly, Burton’s figures are more accurate than most, and the total he gives of 42 monks and seven lay brethren at Meaux in 1349 is likely to be a true record. Only ten of Meaux’s monks and not a single lay brother survived the Black Death that summer. In 1396, almost 50 years later, when Burton could count them for himself, there were still no lay brethren and just 26 monks in his community.14

Among monks and nuns plague mortalities were not the only cause of declining recruitment. Another was changing fashions in religion. Nevertheless, it is a fact that very few religious houses in late-medieval Britain ever fully recovered their pre-plague numbers, and this was as true of such huge and well-endowed communities as Christ Church (Canterbury) as of only moderately wealthy abbeys like Burton’s Meaux. Christ Church was the premier cathedral priory of medieval England. And one of the consequences of the community’s great wealth and of its unbroken post-Dissolution life as secular cathedral was the preservation of unusually complete archives. At sleepy provincial Meaux, a Cistercian abbey with no great tradition of record-keeping, Burton had had to rescue “many ancient documents and long forgotten parchments … some [of] which had been exposed to the rain, and others put aside for the fire”.15 But the estate and other records of a great Benedictine landowner like Christ Church Priory were always acknowledged to be among the more precious of its assets. There is no doubting the report at Christ Church of only four mortalities in the Black Death. But then the pestis secunda of 1361 carried off another 25 of the priory’s community, while cutting a further swath through its tenantry.16

Concerning those Canterbury tenants, it has been argued persuasively from the surviving estate records that the two earliest plagues were indeed “more purgative than toxic”. But there was still no sign in the 1390s of population recovery. And after a last Indian summer of satisfactory returns on their manors, even the monks of Christ Church felt the pinch of real recession.17 Two important fifteenth-century documentary sources, complementary from 1395 to 1505, establish the circumstances which inhibited recovery. One of those sources, the Canterbury profession lists, recorded individual admissions to the fraternity. The other, the priory’s obituary lists, resumed in 1395 after a full generation’s silence following the plague of 1361, giving time, cause and circumstances of each death.18

These records together, for eleven decades at Canterbury, furnish a unique source of mortality data. And what they show with shocking clarity at this well-founded house is the continual stalking presence of sudden death. At Christ Church, through this time, almost a third of the monks’ deaths resulted from frequently recurring epidemic diseases, of which bubonic plague, tuberculosis and the sweating sickness were the great killers. Tuberculosis, in particular, carried off the younger monks, reducing life expectation at birth, already chronically low in late-medieval England, to less than 23 years. No fewer than 17 times during these decades the annual crude death rate at Canterbury soared to above 40 per thousand. By any recognized standard of today, these are appalling statistics. Yet they derive neither from the Third World nor from the truly disadvantaged urban poor, but from a late-medieval community of wholly exceptional privilege: well watered, well fed and well housed.19

Privileges of this kind must explain in some degree the early immunity of the Christ Church monks from the Black Death. Yet other great religious houses, as advantaged in every way, were worse hit. Westminster ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- Preface

- 1 Mortalities

- 2 Shrunken towns

- 3 Villages in stasis

- 4 Impoverished noblemen and rich old ladies

- 5 Knight, esquire and gentleman

- 6 Of monks and nuns

- 7 Like people, like priest

- 8 Protest and resolution

- 9 Architecture and the arts

- 10 What matters

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index