This is a test

- 388 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

This is the third major revision of a text first published in 1982 with the title Urban Geography: A First Approach and in 1990 as Cities in Space: City as Place. The study of urban geography remains an important part of the geographical curriculum both in schools and in higher education. This book analyses life in an urban society and in a world which is being transformed by the processes of urbanization: to study urban geography is to study environments and phenomena significant to our everyday lives. This is an introductory text which aims to present both more traditional and newer approaches to urban geography in an accessible and educational way.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Cities In Space by Prof David Herbert,Dr Colin Thomas in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Education & Education General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1

The concerns of urban geography

Griffith Taylor could still state in the 1940s, at a time when many classic urban studies had already been written, that urban geography was in its infancy. This statement reflected the restricted visions of geography as a discipline at this time, centrally interested in the relationship between people and environment and the natural science paradigm of environmentalism. Most geographies studied rural and regional landscapes with the few urban studies reflecting their disciplinary context. There were

- site and situation studies, concerned with the physical qualities of the land over which urban settlements had developed and with locational qualities

- urban settlement studies that examined the spatial distributions of towns and cities, networks of urban places and their connectivities, and notions of hinterlands or market areas

- urban morphologies that studied the internal structure of the city, its morphology or physical fabric, the types of buildings, layout of streets and general town plan, and the relation of these to the historical phases of urban growth

- studies of the historical evolution of the cities and their regional settings that demonstrated the diversity of urban forms, changes over time and cultural variations at a regional scale.

These themes reflected the concerns of geography as a discipline and made for a distinctive urban geography with a particular contribution to the literature. Taylor (1949) used the terms ‘infantile, juvenile, mature, and senile’ to characterize stages of urban growth, classified towns by site and situation – ‘cities at hills, cities at mountain passes’ – and developed examples from different parts of the world. Dickinson (1948) saw the determination of site and situation as being the first task of the urban geographer. This mode of analysis provoked a response from Crowe (1938) who criticized its focus on inanimate objects of landscape rather than upon people and movement. Perhaps the last of the early urban geographies was Smailes’s Geography of Towns (1953) with its themes of the origins and bases of towns, settings, towns and cultures, towns and regions, and morphology. Several of these topical areas from early urban geographies survive in modern forms. Urban morphology, for example, has continued to develop as a research theme, while urban change and its regional variations are too clearly facts of the real world to be ignored, and studies of urban systems have inherited the city and region themes.

The second half of the twentieth century witnessed significant changes in the place of urban studies in geography. At the beginning of the 1950s, it remained at the margins of the discipline: ‘It is rather surprising that there is so little regular study of the characteristics of urban geography (Taylor 1949: 6). For Mayer (1954) urban studies had been one of the most rapidly developing fields of study in geography in the post World War II period. The rate of change gathered pace and in 1982 we suggested that:

Whereas in the early 1950s a separate course on urban geography … was quite exceptional, today the absence of such a course would be equally remarkable.

(Herbert and Thomas 1982: 11)

These statements are evidence of growth but by the later 1990s the ways in which urban geography was researched and taught had changed. First, there was a process of ‘fragmentation with the emergence of many specialisms within urban studies. A broad urban geography is typically followed or replaced by more specialized courses such as urban-social geography, the urban economy, urban services or race relations within cities and the literature reflects this focusing of interest around specific themes. Second, geographers along with other social scientists have found that there are many issues for which it is not necessary to regard the city as a discrete phenomenon or even an appropriate frame of reference. Unemployment and social deprivation, for example, are strongly associated with cities but they are essentially societal problems which find expression in urban places. The whole question of ‘urban as discrete space is contested. Third, with the analysis of a specific issue, like deprivation, disciplinary boundaries need not be a central concern. The shift away from ‘spatial chauvinism’, or the tendency to emphasize space to the exclusion of other key dimensions, reflects the integration of a ‘geography’ into wider social science perspective. Evidence for the widening horizons of urban geographers is accompanied by the increased awareness of non-geographers of the significance of space and place. Sociologists such as Urry (1995), with his study Consuming Places, and economic analyses of regional economic variations in the growth and decline of cities have exemplified this trend by the attention they give to place, space and spatiality.

A further feature of the development of urban geography has been the change in subject matter. Central topics of the 1960s are little regarded in the 1990s, ‘births’ and ‘deaths’ of research topics, reflecting broader trends, have been numerous. The plethora of central business district (CBD) delimitation studies of the 1960s, for example, reflected a preoccupation with land-use and the notion of definable ‘segments’ of urban space, but a 1990s survey of urban financial services would be much more concerned with process and interaction within a global economy and with social networks that were not constrained by geographical space. Central place theory in the earlier period epitomized a positivist geography with its focus on model-building and the generation of spatial laws, whereas later analyses of consumer behaviour signalled a shift to decision-making, behaviouralism and the interplay between structure and agency

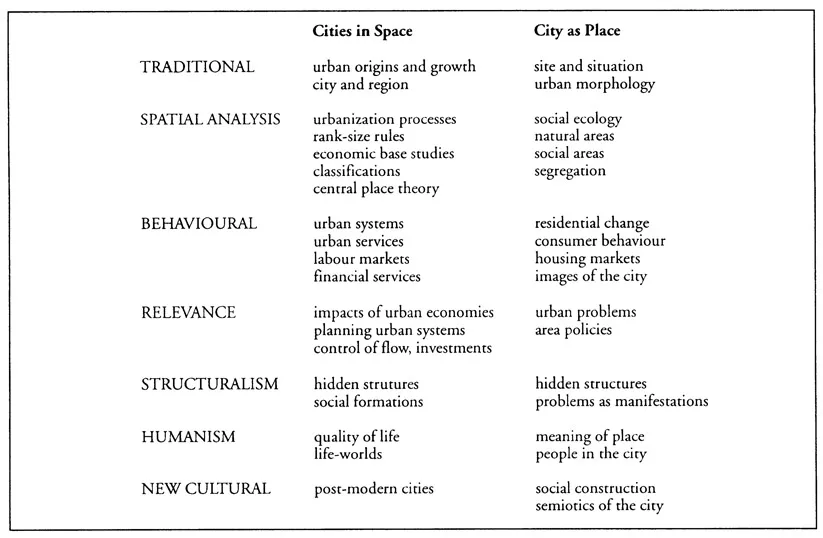

Figure 1.1 summarises this pattern of change as traditional urban geographies emphasizing form and function gave way to studies concerned with the roles of people in the urban system. Initially, with spatial analysis, human activities were summarized in mechanistic ways but stronger interests in activities, feelings, and the richness of human diversity prevailed. Earlier concerns with topics such as rank-size rules, economic base

Figure 1.1 Changing themes in urban geography

studies, urban hierarchies and social areas reflected the thrust towards modelling, quantification and generalization of largely static structures. Later, behaviouralism had its focus on processes, movement and decision-making and, contemporaneously, there was a growing awareness of structuralism and the imperatives of political economy, and the fact that any spatial manifestations of patterns and processes had to be related to the deeper societal forces which underpinned them. The call for relevance also produced a reaction against descriptive studies with their reliance on mechanistic and abstract models, and a renewed interest in humanism prompted the need to understand more fully the affective values people held for place. With the ‘new’ cultural geography of the later 1980s and 1990s, the roles of human agency and the whole meaning of city as place became ever more central to geographies of the city. The road from studies of site and situation to those of the social construction of urban space has been travelled in a relatively short space of time but has been accompanied by a complete transformation in the ways geographers research the city.

Definitions

Issues of definitions, though seemingly tedious, are always necessary. Besides clarifying basic terms, definitions illuminate the subject matter with which they are concerned. One basic definition is that of urban geography per se. Definitions of geography consistently involve the three benchmarks of space, place and environment. These tend to be constants though a particular perspective or paradigm may emphasize one at the expense of the others. Space,

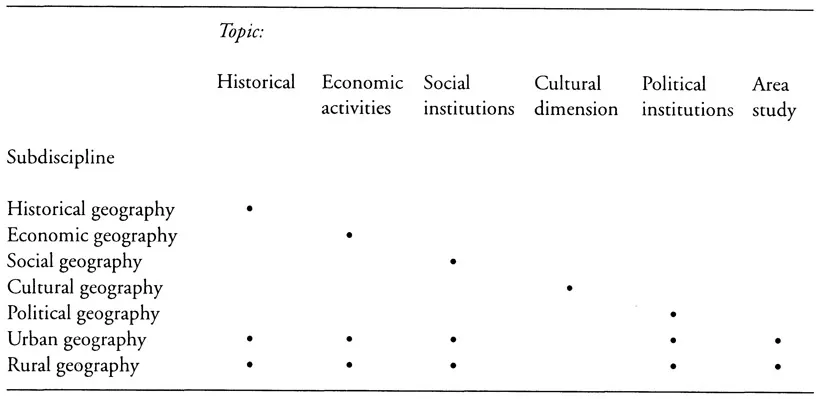

Figure 1.2 Subdisciplines of human geography

for example, was central to the positive science of spatial analysis, place is the key concept for a humanistic and cultural approach, and environment was both a focus of earlier approaches and a new concern of studies of the sustainable city. A definition of urban geography, developed with reference to the discipline as a whole and recent experience of actual research, is

Urban geography studies the patterns and processes which occur between and within urban places; the objective form which these take, the subjective manner in which they are interpreted, and their mode of origin at both local and societal scales.

Among the subdivisions of human geography, urban geography sits somewhat uneasily as Figure 1.2 shows. Whereas economic geography and social geography are distinguished by thematic concerns, urban geography studies an area. Frey (1973) commented on this type of issue with the suggestion that geography considered both single elements or topics which could be studied systematically, or assemblages of areas which could be studied regionally. As an area-based study, an urban geography can cover a catholicity of interest. More commonly, however, studies of individual cities focus upon historical, economic, social and political aspects and have some specialist interest. Urban geography consists of a range of studies of different aspects of the city as a human place and is centrally concerned with those economic, social and political forces that find expression in urban areas. In modern terms these characteristics serve the subdiscipline well. The analysis of ‘the city’ gives it a holistic approach, as much concerned with interactions as with the separate strands of urban life. Another significant definitional issue is that raised by the question: what is urban?

Problems arise because words such as urban, city and town tend to be time and culture-specific evoking different meanings at different historical periods and in different parts of the world. Use of the term ‘city in the UK, for example, is historical and legal, whereas in the USA it has far more ubiquity. Historically, there were city-states in European countries

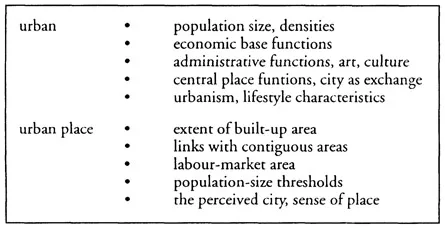

Figure 1.3 Definitions of urban and urban place

such as Greece and Italy and diversity in terminology is embedded in the literature. Practical attempts to define urban have used criteria related to population size, urban functions, and the concept of urbanism (Figure 1.3), and the qualities of these can be summarized.

Population size

Undeniably, urban places are larger than rural places, so the point at which the village becomes a town should be identifiable at some point along the population-size continuum of settlements, though this point varies over time and space. For several Scandinavian countries, including Denmark and Sweden, any settlement which has more than 200 inhabitants is classed as urban in the national census; at least 1,000 inhabitants forms the required threshold in Canada, but 2,500 is the minimum for the USA. Many countries impose much higher thresholds, such as Greece, with 10,000 inhabitants and Japan with 30,000. This diversity is initially confusing, but has some logic if considered within its societal context. Given the physical geography of Scandinavia, for example, and the ways in which its settlement patterns have evolved over time, a settlement with over 200 permanent inhabitants may well be regarded as urban. In a country like Japan, on the other hand, with a relatively limited land area and considerable population pressure, virtually all settlements exceed such a low threshold and 30,000 provides a more realistic line of demarcation. By no means all of the inconsistencies can be explained in these ways, but there are grounds for recognizing order in the apparent diversity. In addition to size, population density is sometimes used on the assumption that urban places have typically higher densities, they are intensive ways of occupying space.

Urban functions

Most official censuses adopt a population-size definition of urban, largely in response to the fact that it is simple and easily measured. There are more telling criteria and Plato provided clues in the Republic when he stated that

The origin of a city is, in my opinion, due to the fact that no one of us is sufficient for himself, but each is in need of many things …. Then the workers of our city must not only make enough for home consumption; they must also produce goods of the number and kinds required by other people …. We shall need merchants … a market place, and money as a token for the sake of exchange … We give the name of shopkeepers, do we not, to those who serve as buyers and sellers in their stations at the market place, but the name of merchants to those who travel from city to city.

Plato developed his argument in terms of other urban needs such as doctors, education, laws and justice and his definition centred on the functions and activities of the city. Urban places have at least two kinds of activities that distinguish them from rural settlements First, they are non-agricultural, and second, they are primarily concerned with the exchange rather than with the production of goods. On the first of these qualities, arguments revolve around the economic base of a settlement or its dominant economic activities. Activities in rural settlements are exclusively concerned with land as a resource and with agricultural production. A simple definition of urban, based upon activities, is one which reflects the dominance of non-agricultural functions. Such a criterion, combined with population-size, is employed in Israel, where a settlement must have in excess of two-thirds of its labour force engaged in non-agricultural work to be classed as urban, and in India, where a threshold of 75 per cent of the adult male population is used.

Other definitions of urban are allied to the economic-base approach. Many settlements have specialized functions which are not rural and can fairly be described as urban. Cities established to control or administer regions of a country were allocated administrative and political functions. Greek and Roman cities are early examples and the tradition has been carried through to modern capital cities such as Canberra, Ottawa and Brasilia. Early urban places were often multifunctional with religion, defence and culture contributing to their primary roles. Religion has provided a key specialist function for many urban places from the religious centres of the Middle East and southern Asia to the cathedral cities of medieval Europe. Although there were craft and mining-dominated urban settlements in the ancient and medieval worlds, the manufacturing centre only really dominated settlement evolution with the progress of industrialization in Europe in the later eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. Industrialization has undoubtedly created settlements which are urban. Distinguished by size, density and the dominance of industrial employment, they were, in Britain at least, the new towns of the nineteenth century. Single-function settlements, whether religious or cultural centres or manufacturing towns, often persist in their original roles over long periods of time. As cities develop, however, they are likely to add to these original roles or even to replace them and this may have the effect of consolidating their urban status.

Another approach to definition has focused upon the functions of distribution and exchange and the marketing role of urban places. Pirenne (1925), in his study of the emergence of urban settlements in medieval Europe, placed great emphasis upon the town as a market place and, for him, the city was a community of merchants. This emphasis on marketing and exchange became explicit in studies of central places and the urban hierarchy emphasizing the roles of urban places as institutional centres for a surrounding territory or hinterland. It is the demand for services that calls the urban settlement into being and once established it develops a network of functional relationships over the region. Work stimulated by Christallers’ (1933) central place theory made this centrality or nodality status of urban places its central focus. Most of the empirical work focused on economic services, particularly retail and wholesale trade, but retained an awareness of the significance of non-economic institutions and services. As Mumford (1938) suggested, the city should not be over-regarded as an aggregate of economic functions, it is above all a seat of institutions in the service of the region, it is art, culture and political purposes. This latter description applies to many early cities.

Urbanism

A further strand in the definitional debate came from sociology and Louis Wirth’s (1938) statement on urbanism as a way of life. Wirth argued that urban places could be distinguished by the lifestyles of their inhabitants which were different from those of rural people. The qualities of population size, density and heterogeneity in their environments combined to make ‘urbanites’ different from ‘ruralites’. Relative anonymity and a paucity of face-to-face relationships were seen as the hallmarks of an urban lifestyle and this hypothesis was supported in the theories of contrast. Tönnies, Weber and Redfield (see Reissman 1964) were among those who postulated rural-urban contrasts such as sacre...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- Preface

- 1 The concerns of urban geography

- 2 Urban origins and change over time

- 3 Third World cities: some general characteristics

- 4 Understanding the urban system

- 5 The urban economy

- 6 The system of control: local government, local governance and the local state

- 7 Transport issues in the city

- 8 Urban services

- 9 The residential mosaic

- 10 Minority groups and segregated areas

- 11 The city as a social world

- 12 Social problems and the city

- 13 Urban trends and urban policies

- References

- Subject index