It is evident, however, that this division of the subject into two parts is artificial, since any exposition of the determinants of the level of the rate of interest must also contain, implicitly, the causes of the phenomenon of interest. Moreover, there is a quite definite break between the first and second part of Bohm-Bawerk’s work. The analysis in the second part is conducted without any reference to the higher valuation of present goods relative to future goods. Since this second part is undoubtedly central for Bohm-Bawerk’s theory of interest, we shall concentrate in our exposition on that section of his work. Thus we gain the additional advantage of being able to avoid a long-winded discussion of the three reasons for the undervaluation of future goods. Accordingly, the sections of the Positive Theory important for the following discussion are Books I and II, which contain Bohm-Bawerk’s theory of capital, and the third section of Book IV which deals with the level of the rate of interest on capital, as well as those ‘Further Essays’ in Volume II which elucidate these sections.

I. The Theory of Capital

Two concepts are important for the understanding of Bohm-Bawerk’s theory of interest: the “period of production” and the “subsistence fund”. Let us start with an explanation of the first.

With a given quantity of services provided by the two original factors of production, labour and land, it is possible to produce more (or, alternatively, better) consumption goods, the longer is the time period which elapses, on the average, between the moment when these services are first applied and the moment when the consumption goods become available. After a certain point, however, the rate of increase of the output of consumption goods will become smaller, and at a further point the increase will completely cease.2 This is Bohm-Bawerk’s law of the greater productivity of the more roundabout methods of production.

Let us consider the simple case, which is assumed in Bohm-Bawerk’s theory, where there is only one original factor of production, labour – the productive services of land being regarded as free. In this case the average period of production is calculated as follows: each unit of labour used in the production process is multiplied by the time which elapses between the moment of its application and the completion of the product; the resulting figures are added up and their total is divided by the number of labour units. In this way we arrive at a weighted arithmetic average as the measure of the average period of production. If, for instance, three labour units are applied two unit periods of time and another two labour units one unit period of time before the consumption good is finished, then the average period of production is calculated as [(3 × 2) + 2]/5 = 1.6 unit periods. It is clear that in this method of calculation those labour units which were applied earlier influence the length of the average period of production much more strongly than do the units which were applied later.

Two special cases may now be considered. One is characterized by the fact that all inputs are applied simultaneously at the beginning of the period of production and no further inputs are needed between this point of time and the time when the consumption good becomes available. This case played an important role in capital theory; it is usually illustrated by the example of trees which grow of themselves once they have been planted, or by the example of wine which matures of itself once it has been stored. Here the absolute period of production – the time which elapses between the first input of productive services and the point when the goods are ready for consumption – is identical with the average period of production as calculated by Bohm-Bawerk’s method. It is not on this case, however, that Böhm-Bawerk has based his discussion of the determinants of the rate of interest.

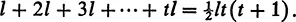

The second special case is that of the “even flow” period of production (in Bohm-Bawerk’s terminology, the gleichmãssig ausgefüllte Produktions-periode). Here the application of productive services is spaced uniformly through the absolute period of production: in each unit period throughout the process of production the same quantity of productive services is added. Böhm-Bawerk usually has this case in mind. The average period of production is here equal to exactly half the absolute period of production, a fact which can be established as follows: Suppose that the same quantity l of labour inputs is applied at each stage of the production process and that the last stage is one unit period distant from the moment at which the product is ready for consumption, the penultimate stage two unit periods and the first stage t unit periods distant from this moment. Then the sum of the products of the labour inputs and their respective time distances from the moment of completion of the consumption good is equal to

If we divide this expression by the total input of labour units lt, we obtain . Finally, if we conceive of the unit period as small enough to be able to neglect the half period in this expression, we may say that t/2 is the average period of production.

Böhm-Bawerk also uses the concept of an “average social period of production”, without, however, explaining how this average of the production periods of individual goods is to be calculated. He seems to think that this is merely a problem of practical measurability, and that the logical precision of the concept would not be affected if the problem should in reality be insoluble.

Böhm-Bawerk does not altogether neglect durable goods. He distinguishes between durable production and durable consumption goods.

With respect to the latter he claims the validity of a rule similar to – but not identical with – the law of the greater productivity of longer production periods. This rule, incidentally, had already been stated by John Rae. The more services of the original factors of production are used, for instance, in the construction of a house, the longer will be the useful “life” of this house. Moreover, the “lifetime” of the house will increase at a faster rate than the total input of factor services. If 30 man-years are necessary to build a house which will last, say, 30 years, then 50 man-years may build one which will last perhaps 60 years. To avoid misunderstanding it should be stressed that the application of these 50 man-years need not necessitate a longer construction period for the house than that of 30 man-years; 50 man-years can be applied during one single calendar year, exactly as can 30 man-years. However, in the case of waiting for the services of such consumer durables, the concept of the “waiting period”, which Böhm-Bawerk uses in this context, has a meaning quite different from that in the previously discussed case of the production of non-durable consumer goods. In the case of a durable consumer good, such as a house, one does indeed wait for future services; this waiting, however, is here accompanied by the enjoyment of the present services of the house, which are true consumer goods, while in the previously treated case of the production of non-durable consumer goods real “abstinence” is required since the consumer goods do not become available until the period of production has been completed.

Although it is quite true that the useful life of durable production goods follows the same rule as that of durable consumption goods, Böhm-Bawerk subsumes this case under the rule of the greater productivity of more roundabout methods of production. The extension in the useful life of durable production goods he considers to be simply one of the ways in which the period of production can be extended. To him, waiting for future services of durable production goods is identical with waiting longer for consumption goods, a kind of waiting which is not accompanied by a concurrent yield of consumption goods.3 The objection immediately arises that such distinction between durable production goods and durable consumption goods is not justified. A shoe-making machine, exactly like a house, produces consumer goods as long as it remains in use, and waiting for its future services is accompanied by a continuous receipt of consumption goods in the form of shoes. In fact, Böhm-Bawerk includes in both cases in his average period of production the average period of waiting for the services or the consumer goods which are yielded by the durable goods.4 Thus his method of calculation in fact contradicts his theoretical distinction. However, as Böhm-Bawerk leaves durable goods out of account in his discussion of the determinants of the level of the interest rate, we can disregard them in the following exposition.

Bohm-Bawerk’s law of the greater productivity of more roundabout methods of production is valid at every point in time. He does not deny the possibility of technical inventions which might have the effect of shortening the average production period, but he asserts that any known technical methods which are not in use, even though they yield a greater product, must entail longer periods of production than the processes actually used; for if such were not the case, they would be applied instead. According to Böhm-Bawerk there exists at any time a long list of known technical processes which, because they involve longer production periods, yield more output than the methods actually used. It is the level of the rate of interest which makes it unprofitable at a given moment to adopt these processes.

How does Böhm-Bawerk “prove” the existence of his law? The “law” is in fact an empirical rule which he undertakes to prove from the observation of reality. At the same time he supports it with arguments of a general character. He repeatedly stresses that the law cannot be derived logically from a given set of premises, and he admits the impossibility of concretely measuring the period of production.

A collation of all the arguments which Böhm-Bawerk brought to bear on this question yields the following result. In the first place, he endeavours to “prove” his law by reference to a great number of specific examples. These are typified by the famous fishery example: the transition from fishing by hand to fishing with a hook and then to fishing with a net f...