![]()

Chapter 1

Water Scarcity

All peoples … have the right to have access to drinking water in quantities and of a quality equal to their basic need.

UN Water Conference, La Plata, 1977

At the end of 1984, 21 African countries were suffering from what the United Nations calls “abnormal food shortages”. In human terms, this meant that hunger stretched its dread hand in a belt across and down Africa, starting from the Cape Verde Islands off the west coast, moving over the Sahel to Ethiopia and the Sudan, and then extending down into Botswana, Mozambique and Lesotho.

In this area of more than 14 million square kilometres – one and a half times the size of the whole of Europe – some 200 million people, 40 per cent of Africa’s total population, didn’t know where their next meal was coming from. The death rate in some of the emergency camps that were set up to house the starving was more than 100 a day. By the time the crisis ended the following year, hundreds of thousands of Africans had either starved to death or died indirectly from malnutrition.

A similar event, causing millions of deaths, had swept through Africa in the early 1970s. Why should famine hit the same continent so disastrously in the space of two short decades? What caused the food crises of the 1970s and 1980s?

Drought, world recession, and civil and military conflicts all played their part. But the real truth was that Africa was short not so much of food as of water.

A shortage of water is not the same as drought. Droughts are exceptional meteorological events. Water shortage in much of Africa – and elsewhere – is not exceptional but endemic, a part of everyday life. The central thesis of this book is that many countries, and not only those in Africa, are now chronically short of water. Most of them are likely to become more so in the future.

While the symptoms of water shortage are easy to identify, its causes are not. Malin Falkenmark, from Stockholm’s Natural Science Research Council, distinguishes four different causes of water scarcity:

- aridity, a permanent shortage of water caused by a dry climate;

- drought, an irregular phenomenon occurring in exceptionally dry years;

- dessication, a drying-up of the landscape, particularly the soil, resulting from activities such as deforestation and over-grazing; and

- water stress, due to increasing numbers of people relying on fixed levels of run-off.

The first two of these relate to the climate, the second two to changes that result from human activity. For the moment, it matters little which of these causes is the most important, and which results in the greatest suffering. Suffice that, jointly or separately, they are depriving millions of people of the water they need to live anything approaching a decent life.

Water shortages are also a potential problem in many developed countries. However, industrial nations can usually resort to buying their way out: through the use of expensive energy, expensive technology and expensive investments they can install the wherewithal to recycle their water, or even to desalinate sea water.

Developing countries, trapped in poverty and debt, have no such option. Those that suffer from serious water shortages are faced with a cruel dilemma: they must either limit their use to water that has not previously been used; or they must make do with used but untreated water.

There are few meaner examples of Hobson’s choice. To choose to limit water use can prevent progress, reduce food production, threaten livestock production and imperil human survival. To choose to reuse untreated water, on the other hand, is an open invitation to disease.1

The Costs of Water Shortage

What does this mean in practice? A shortage of water can prevent almost everything from being done. Consider the following statistics: you need at least 3 litres of water to produce a tin of vegetables, 100 litres to produce one kilogram of paper, 4500 litres to produce one tonne of cement, 4.3 tonnes to manufacture one tonne of steel, 50 tonnes to manufacture a tonne of leather and no less than 2700 tonnes to make a tonne of worsted suiting.

Even more importantly, the average human – of which there are now more than 5 billion on the planet – needs to drink a litre or so of water a day to stay alive. That is, if he or she is adequately fed. Water requirements of those who are on starvation diets are dramatically higher, because food itself consists mainly of water.

But this is not the most important statistic of all. There are few places in the world where survival is threatened directly by lack of drinking water. But there are many where a lack of food apparently threatens survival. As this book will make clear, it is often not food that it is in short supply in these places, but the water with which to grow it. To grow an adequate diet for a human being for a year requires about 300 tonnes of water – nearly a tonne a day. There are many, many places where there is not nearly enough water to do this.

Water is thus the one essential requirement of all forms of food production. No water, no food. It is no coincidence that fewer people go hungry in wet countries than in dry ones.

Water is thus a limiting factor in human development, and water shortages are heavily implicated in humanity’s present plight. If better means of conserving and using the water we have are not found, development will remain slow in many of the poorest areas of the world for decades, possibly centuries.

Water deficits are not restricted to developing countries, nor even to arid or semi-arid areas. The more water that is needed, the more likely is a prospective deficit. Industrial countries, which know well the value of the water they use, will go to immense lengths to avoid the deficits that might threaten to halt their development. In the Soviet Union, for example, the north of the country has plenty of water but water deficits in the south are expected to reach as much as 100 cubic kilometres a year by the end of the century. One (recently cancelled) plan to overcome the deficit involved altering the course of northward-flowing rivers towards the south, through the construction of transcontinental canals. China has already undertaken projects of this type and the United States has plans to.

Such grandiose schemes are fraught with problems. They have unpredictable ecological consequences; except in the very largest countries, they require complicated international agreements that can be enforced; and they require massive funding in a market still fighting over what should be done over repayment of previous levels of Third World debt. Furthermore, in many areas of the world, water-rich areas do not lie near enough water-poor ones to make such schemes economic. Most of the developing countries that are short of water are therefore condemned to a different, and unsavoury, solution: the use of dirty water.

Welfare and Illfare

The success of civilized society is due less to the invention of the steam engine, the spinning jenny and the other technological wonders of the industrial revolution than it is to the invention of cleanliness. Had Dr John Snow, in 1854, not been able to trace an outbreak of cholera to the Broad Street Well in London’s Golden Square, we might never have emerged from Dickensian squalor. But he did, and in the process of showing how the well was being contaminated from a nearby privy used by those carrying the cholera bacteria, he revealed for the first time the link between disease and water that has always been man’s greatest plague.

Number of people in developing countries with and without an adequate supply of drinking water and sanitation; 1980 and 1990

But the birth of sanitation was a troubled one. After Snow’s discovery, the London authorities ordered that wastes be discharged into the run-off system that carried storm water to the Thames. The load of organic matter thus deposited in the river was more than it could absorb, and the stench became so intolerable that the Houses of Parliament were forced to hang burlap sacks saturated in chloride of lime in their windows so that Members could continue the business of the day. This no doubt hastened the development of modem sewage treatment, which first began to be practised in the late nineteenth century.2

In developing countries, however, most drinking water is contaminated and most sewage is left untreated. A 1975 survey by the World Health Organization (WHO), which covered 90 per cent of developing countries (excluding China), showed that only 35 per cent of the population had access to relatively safe drinking water and only 32 per cent had proper sanitation. In other words, 1200 million people lacked safe drinking water, and 1400 million lacked sanitation.

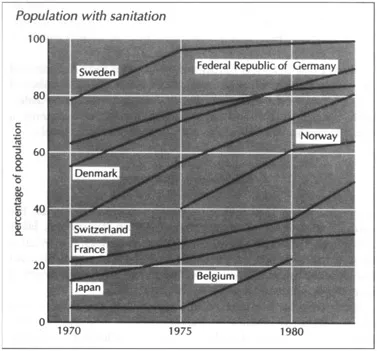

The problem is by no means restricted to developing countries. In the OECD countries, for example, the percentage of the population served by a waste water treatment plant in 1983 ranged from 2 per cent for Greece and 30 per cent for Japan, to 100 per cent for Sweden.3

The United Nations International Drinking Water Supply and Sanitation Decade (1981-90) was launched to help rectify the scandalous situation in the developing countries. Its aim – that of providing everyone with drinking water and sanitation during the Decade – was nowhere near met. On the other hand, many millions of people were provided with proper water and sanitation and, in spite of population growth, a higher proportion of the population now enjoys safe water and sanitation than at the beginning of the Decade. According to the official estimate, access to a safe water supply in developing countries rose from 44 to 69 per cent over the Decade; proper sanitation was provided to 54 per cent of the population at the end of the decade, compared to 46 per cent at the beginning. In the cities, things are better than these averages imply; in rural areas, they are worse.4

Behind these facts lie some grim statistics. Water-borne disease, the complaint that dictates the “illfare” of most of the world’s population, is ever-present in developing countries. According to the WHO, as many as 4 million children die every year as a result of diarrhoea caused by water-borne infection. Each could be saved by a simple packet of sugar and salts costing 7p. Better still, the risk could be removed completely if clean water were universally available, and sewage properly treated.

Proportions of European and Japanese populations with sanitation

Dirty water is responsible for more than diarrhoea. At the time of the United Nations Water Conference, held in La Plata in 1977, estimates were made of how many people were suffering from 30 of the world’s major water-related diseases. Many of these diseases are not contracted from contaminated drinking water but are carried by vectors such as mosquitoes and snails that live and breed in irrigation water, river water and lakes. Water-borne disease, it was estimated, was affecting 400 million people with gastroenteritis, 200 million with bilharzia (caused by blood flukes carried by a waterborne snail), 200 million with filiariasis (threadworm), 160 million with malaria and 20-40 million with onchocerciasis (a disease caused by the nematode worm).

The overall effect on human health is virtually incalculable. Nevertheless, attempts have been made. According to one WHO official, dirty water was the cause of 27,000 deaths a day in 1986.5

Given these facts it is hardly surprising that the WHO should attach such great importance to clean water. “The number of water taps per thousand persons”, declared Halfdan Mahler, WHO’s Director-General in the early 1980s, “will become a better indicator of health than the number of hospital beds.”

World Water Resources

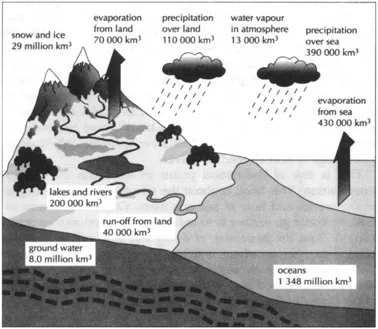

There are about 1360 million cubic kilometres of water on the earth. If all the water on the planet – from the oceans, lakes and rivers, the atmosphere, undergound aquifers, and what is locked up in glaciers and snow – could be spread evenly over the surface, the earth would be flooded to an overall depth of some three kilometres.

More than 97 per cent of this water is in the oceans. The rest – about 37 million cubic kilometres – is fresh water but most of that is of little use since it is locked in icecaps and glaciers. Current estimates are that about 8 million cubic kilometres are stored in relatively inaccessible ground water, and about 0.126 million cubic kilometres are contained in lakes and streams.

How much is locked up in the water “larder”, however, is much less interesting than how the larder is refilled. Only the renewable fraction of the world water cycle can actually be used for sustainable development. If ground water is used faster than it is replenished, then water reserves are being mined just as surely as is the coal that comes from deep underground, and the oil and gas from under the sea bed.6 A great deal of ground water is currently being mined, notably in Libya and the Midwest of the United States; Bangkok and Beijing, to quote just two examples, are supplied largely from mined groundwater reserves.

The global hydrological cycle

Rainfall and Evaporation

The rain that falls on the land averages some 725 mm a year. In some places it rains gently throughout most of the year and in others torrential rains occur for one or two months a year, the rest of the year being almost rain-free. In some places, such as the Atacama Desert, rainfall is effectively zero; and there are places in tropical forests where there are more than 5 metres of rain a year. In the world’s arid areas, where more than 600 million people live, rainfall is less than 300 mm a year. Crops can be grown only under irrigation.

Rainfall is balanced every year by the world’s run-off –...