This is a test

- 298 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

First Published in 1992. A rare behind-the-scenes look at the rehearsal sessions of acclaimed directors and actors. Cole offers a view of what is often hidden from the public eye: what actors and directors do when they prepare a dramatic text for performance.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Directors in Rehearsal by Susan Cole in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Media & Performing Arts & Performing Arts. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

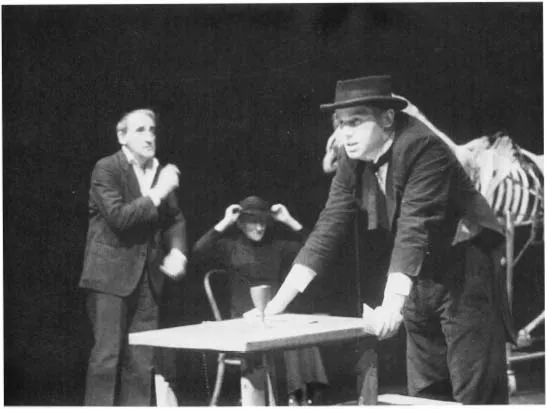

Fig. 1.1. Polish director Tadeusz Kantor onstage during a performance of Let the Artists Die by Cricot 2 Theatre at La Mama. Photograph by Gerard Vezzuso.

1

A Hidden World

It is almost 7:30 p.m., Sunday evening, October 13, 1985, at La Mama Annex in New York City where Polish writer and director Tadeusz Kantor’s Let the Artists Die is about to be performed. Tadeusz Kantor is onstage, alternately peering out at the audience and looking at his wristwatch. He exits, enters again, exits. When the play begins, he is onstage, wearing a black suit with an open-collared white shirt, seated prominently on a wooden chair, on a diagonal to the main stage action, his back toward the audience. Throughout the performance the director’s hands are in almost continual rhythmic motion, seemingly in response to both sound and action. In addition, his fingers often gesture to indicate sound cues and, occasionally, cues for actors’ positions or movements. Once he turns to glance over his shoulder and either speaks or mimes speech to the sound booth. Throughout the one and a half-hour performance the director’s concentration on the actors is intense, penetrating. Sometimes he touches or is touched by an actor, or makes eye contact. Sometimes he moves or holds stationary a particular stage prop (a chair, a skeleton-like horse). At one point he is handed an actor’s socks, shoes, and trousers; the director neatly folds the socks into the shoes and then folds the trousers, keeping them in his lap until they are later plucked out by the actor who, along with other actors, whirls by him in a circular motion around the stage. Twice the director leaves the stage: once when the exit he sits by requires wider access and again when the full cast is moving in intricate patterns in the small space. The energy level of the actors remains the same, neither decreasing nor increasing visibly, while the director is offstage.

Kantor’s characteristic onstage gesture is a kind of world-weary flick of the right wrist. It is an ambivalent and a highly ironic gesture, both calling something into being and dismissing it. The gesture seems to say: “Have done with it,” i.e., do it and stop doing it. This is exactly what the director is empowered to command in rehearsal and unable to control in performance. Stopping and starting, energizing and eliminating, presiding over a birth and declaring a stillborn—these are directorial functions which can be enacted only in rehearsal, not during performance. The performance is the after-image of processes set in motion—explored, nourished, made fit for growth, realized—during the “work” of rehearsal.

Kantor’s visible presence during performance is a striking stage image of the fantasy of total control and, at the same time, of the irony of the director onstage without directorial power. In his “unsuccessful” attempt to recreate the conditions of rehearsal by intruding himself into performance, Kantor is redefining the boundary, for a director, between rehearsal and performance. The almost involuntary flick of his wrist is an acknowledgment of the director’s difficulty in letting go of the actors and of his rehearsal role: he flicks them away but he would be forever “restarting” them, reshaping their life on stage. The Ariels of this Prospero are unwillingly given their freedom in this controlling yet dismissive gesture.

My observation of the rehearsal work of ten professional directors, five female and five male, was completed between June 26, 1985 and October 15, 1989. (In my Epilogue, I describe the additional experience of observing, and unexpectedly becoming the dramaturg for, an amateur production of Sophocles’ Antigone at the college where I teach.) In all cases I attended at least one performance of the work observed in rehearsal but, throughout, my passionate attention was on “not the result of making but the making itself.”1 In documenting rehearsal as a process, whose traces are often lost in performance, I hope to offer glimpses of a hidden world, a realm usually—and with good reason—veiled to observers. George Bernard Shaw is particularly firm in defense of the theatrical taboo against observers: “Remember that no strangers should be present at rehearsal. … Rehearsals are absolutely and sacredly confidential. … No direction should ever be given to an actor in the presence of a stranger.”2 Molière, inscribed as a character in his own play L’Impromptu de Versailles, proclaims this proscription from the stage itself in a performance of rehearsal:

Molière: Monsieur, these ladies are trying to tell you that they prefer not to have any outsiders present during rehearsals.

La Thorillière: Why? I’m not in any danger, am I?

Molière: It’s a tradition in the theater.3

To observe directors and actors in rehearsal is clearly a delicate undertaking; it can be perceived as an intrusion upon, and even a repression of, the conditions necessary to rehearsal (e.g., risk-taking, spontaneity, intimacy). But there is no other way to document the collaborative creation of rehearsal except to be present there.4 My previous experience as an invited observer at Lee Strasberg’s Actors Studio and at Joseph Chaikin’s rehearsals of Trespassing allowed me to learn techniques of “being present” that seemed unlikely to disrupt or betray the special conditions of rehearsal work.5

From the beginning I decided to make use of a notebook rather than a tape recorder. Some interviews were initiated without so much as a notebook, in corridors or doorways. All interviews and quoted commentary of actors and directors occurred during the rehearsal period. When members of the company spoke to me during breaks in rehearsal, they usually spoke fairly unselfconsciously and spontaneously. Later I might ask if we could go back over what I heard, checking accuracy and sometimes phrasing. It is possible that after I became a fixture in rehearsal rooms, visibly writing almost continuously, my continuing to write as people spoke to and near me became a part of the landscape. In almost every rehearsal I observed, I was told that I appeared to be writing down “everything.” Since my focus seemed decentered, no one in particular at any given moment appeared to be under the spotlight of my attention. In this technological age, when to be exposed publicly is increasingly to be recorded on tape, film, or video, my simply taking notes in a room of other notetakers—the stage manager, production stage manager, lighting, costume, set, and sound designers, various production assistants, speech and text consultants, choreographers, and, at times, the director and actors themselves—was perhaps less invasive than I had originally feared.

The following chapters present what, to my knowledge, has never before been documented in book form:6 the rehearsal practices of a variety of contemporary American directors.7 The rehearsals I observed range from Peter Sellars’ two-actor production of Two Figures in Dense Violet Light to Lee Breuer’s cast of approximately a hundred performers in The Warrior Ant; from JoAnne Akalaitis’s opera-theatre workshop production of Voyage of the Beagle to Emily Mann’s documentary drama, Execution of Justice (one of the few Broadway productions written and directed by a woman); from the collaborative creation of script and staging in Elizabeth LeCompte’s rehearsals of Frank Dell’s The Temptation of Saint Antony to the agreed-upon non-collaboration of Richard Foreman with writer Kathy Acker, set and costume designer David Salle, and composer Peter Gordon during the rehearsals of The Birth of the Poet. I consider traditional directing styles and texts (Shakespeare’s Hamlet, Chekhov’s The Cherry Orchard and Uncle Vanya) as well as experimental directing styles and texts (Kathy Acker’s The Birth of the Poet, Heiner Müller’s Hamletmachine, Robert Wilson’s The Golden Windows); auteur-directors such as Liviu Ciulei, Richard Foreman, and Robert Wilson as well as the collective theatre enterprise of the Wooster Group and Mabou Mines director Lee Breuer.

In the writing of this book I at one point hoped that a single metaphor might unequivocally claim a position of central power. I found a suggestive clue in the etymology of the word rehearse, which derives from the Middle English rehercen and the Old French rehercer, “to repeat,” originally “to harrow again”: re-, “again” + hercer, “to harrow,” from herce, a harrow.8 A harrow is a heavy frame of timber or iron, set with iron teeth or tines; it is dragged over already ploughed land in order to break up clods of earth, pulverize and stir the soil, uproot weeds, eliminate air pockets that would prevent soil-to-seed contact, and cover the seed. In short, the harrow is a secondary tillage instrument: all the elements of growth are usually present before the harrowing that “fits” the soil for planting.9 The metaphor of rehearsal as a harrowing—a fine breaking down of the playtext in preparation for a first or simply another planting in the soil of performance—captured my imagination for several months.

And yet metaphors in themselves are provisional: they posit connections, and the very act of positing a connection implies that there are other connections. Against the possibility of one controlling metaphor arises a proliferation of metaphors, many of them substantiated by theatre practitioners themselves. Here, for example, is a list of selected metaphors for the director:

Director as Father-Figure10

Director as Mother11

Director as Ideal Parent12

Director as Teacher13

Director as Ghost, Invisible Presence14

Director as Third Eye15

Director as Voyeur16

Director as Ego or Superego17

Director as Leader of an Expedition to Another World18

Director as Autocratic Ship Captain19

Director as Puppet-Master20

Director as Sculptor/Visual Artist21

Director as Midwife22

Director as Lover23

Director as Marriage Partner24

Director as Literary Critic25

Director as Trainer of Athletic Team26

Director as Trustee of Democratic Spirit27

Director as Psychoanalyst28

Director as Listener, Surrogate-Audience29

Director as Author30

Director as Harrower/Gardener31

Director as Beholder, Ironic Recuperator of the Maternal Gaze32

Of all these analogues, that of the maternal gaze seems the most promising, though insufficient to encompass the whole director-actor experience. Any reader with an interest in the Lacanian concept of the gaze will note intermittent references to it throughout. I shall have recourse to the “gaze” when it seems helpful or suggestive but shall not employ it as an organizing principle of the present book. While this may result in some lack of theoretical rigor, it may at the same time protect against some of the dangers of theoretical rigor.

My own spectatorial relation to the director in rehearsal temporarily reverses the usual subject and object positions and at times puts the directorial gaze in question. Gazing can, of course, be many things. The “phallocentric gaze,” which defends against, controls, and wards off the threatening aspects of the female, consigning her always to the object position, is one-way and appropriative. But there is another and earlier kind of gazing: the maternal gaze, which may become the mutual gaze of mother and infant. E. Ann Kaplan raises the question whether it is possible “to imagine a male and female gaze … that would go beyond male obliteration of the female, or female surrender to the male, indeed beyond gender duality, into an unconscious delight in mutual gazing that might be less exclusionary and less pained.” My observation of directors in rehearsal suggests not that women take on the masculine role as “bearer of the gaze and initiator of action,”33 but that the director’s gaze, if not “beyond gender duality,” is more feminine than masculine and that the male director’s appropriation of the female gaze is often more acceptable to the actors than the female director’s reinvesting of the maternal gaze with its former potency. The directors I observe might well say with Proust: “Our work makes mothers of us.”34

Should our work also make theorists of us? Edward Snow has suggested that “theory se...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Table of Contents

- Acknowledgments

- List of Illustrations

- 1 A Hidden World

- 2 Elinor Renfield Directs The Cherry Orchard

- 3 Maria Irene Fornes Directs Uncle Vanya and Abingdon Square

- 4 Emily Mann Directs Execution of Justice

- 5 JoAnne Akalaitis Directs The Voyage of the Beagle

- 6 Elizabeth LeCompte Directs Frank Dell’s The Temptation of Saint Antony

- 7 Richard Foreman Directs The Birth of the Poet

- 8 Robert Wilson Directs The Golden Windows and Hamletmachine

- 9 Liviu Ciulei Directs Hamlet

- 10 Peter Sellars Directs Two Figures in Dense Violet Light

- 11 Lee Breuer Directs The Warrior Ant

- 12 Epilogue

- Notes

- Selected Bibliography

- Index