![]()

Book 1

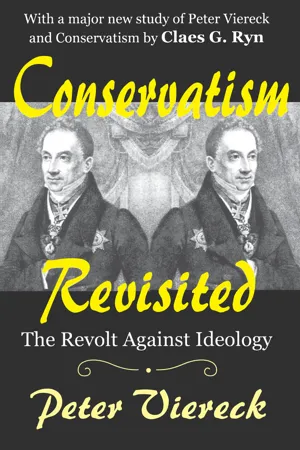

Conservatism Revisited

![]()

1

Heritage Renewed: The Conservative Principles

"The enemy we could not buy or break was the aristocratic individualism of the ordinary citizen of the west. If only we had hanged—as Himmler was always itching to do—all those outdated legalists, with their squawks about moral dignity, then our movement would have swept the world. "

—From an interview with a Nazi prisoner of war

"[l]n our opinion morality is entirely subordinate to the interests of class war. Everything is moral which is necessary for the annihilation of the old exploiting social order."

—Lenin's address to a group of young communists

"[My]measures will not be sicklied over with legalistic doubts. . . . Here is not justice that I have to exercise; here I have only to annihilate."

—Goering's address to the German police, 1934

"Our civilization will break down if the school fails to leach the incoming generation that there are some things that are not done. "

—Gaetano Salvemini

Certainly it is true that the stairway of history "is forever echoing with the wooden shoe going up, the polished boot descending." Yet the stairway itself does not change. Nor do history's problems and principles. As Metternich insisted to the French premier Guizot: 'The conservative principles are applicable to the most diverse situations."1

A political philosophy in the abstract is incomplete. Its concrete manifestations become clearer through an analysis of some actual historical figure who tried to put the theory into practice. Clemens Metternich, as chancellor and foreign minister of the Hapsburg empire and guiding spirit of the "Metternich era," has become conservatism's lasting symbol; in modern eyes, conservatism at its most unpopular. He is an object lesson not only of short-run conservative action but of an enduring conservative philosophy. His latter aspect will be referred to as "Professor Metternich." The phrase is borrowed not only from his own exclamation after his downfall ("I am no longer a Minister; I am Professor Metternich!")2 but from the more detached judgment of Disraeli: "The only practical statesman who can generalize like a philosopher. . . . What a different man he really was to what those fancied him who formed their judgment in the glitter of Vienna! Had he not been a Prince and a Prime Minister, he wouid have been a great Professor."3

In his memoirs, Guizot analyzed in Metternich this same dualism of the practical statesman and the philosophical "professor": "One saw in him a rich, complex, deep intelligence unfold itself, zealous to seize and utter general ideas and abstract theories and at the same time a supremely sharp, practical sense."4 Perhaps the final word on Metternich will turn out to be one of the very first. Writing with strange detachment in the midst of revolution exactly a century ago, Gustav von Usedom summarized in 1849:

Do not believe what the moment will decide about Prince Metternich. important men, who worked upon time so Powerfully as he, cannot possibly be judged dispassionately. Metternich was a principle: a banner which one part of the century followed while another part stood up against it and toppled it in the end.5

If Metternich was a "principle," both his friends and his enemies are agreed on its label: conservatism. On their definitions of this label, they can never agree. Each attempt at definition—and this opening chapter is such an attempt—may seem private and arbitrary to those who disagree. The author is "well aware" (to use that cliche of defensive rhetoric) that any good liberal can give far less flattering definitions of conservatism, not to mention the familiar Marxist objections.

Conservatism is a treasure house, sometimes an infuriatingly dusty one, of generations of accumulated experience, which any ephemeral rebellious generation has a right to disregard—at its peril. To vary the metaphor: conservatism is a social and cultural cement, holding together what western man has built and by that very fact providing a base for orderly change and improvement.

But not all the past is worth keeping. The conservative conserves discriminate^, the reactionary indiscriminately. Though the events of the past are often shameful and bloody, its lessons are indispensable. By "tradition" the conservative means all the lessons of the past but only the ethically acceptable events. The reactionary means all the events. Thereby he misses all the lessons.

The conservative principles par excellence are proportion and measure; self-expression through self-restraint; preservation through reform; humanism and classical balance; a fruitful nostalgia for the permanent beneath the flux; and a fruitful obsession for unbroken historic continuity. These principles together create freedom, a freedom built not on the quicksand of adolescent defiance but on the bedrock of ethics and law.

By themselves these principles sound hopelessly vague. They are clarified when specifically "applied to the most diverse situations." This will be attempted by briefly recording the conservative stand on each of the following diverse problems, surveyed in the following order: humanism and education; means vs. ends; nature vs. law; social change after industrialism; aristocracy; the welfare state; individual vs. majority; priority of non-economic motives; political application of Christianity; obscurantist misapplication of Christianity; "the west" as a Greek-Roman-Jewish-Christian amalgam; romantic revolt against form and reason; the mass-man as totaiitarian; nationalism vs. Europe.

The core and fire-center of conservatism, its emotional elan, is a humanist reverence for the dignity of the individual soul. This is incompatible with fascist or Stalinist collectivism; incompatible with a purely mechanistic view of man; incompatible with a purely economic view of history.

In the universities, humanism inspires the return to literature and the classics, away from the shortsighted cult of utilitarian studies. A crassly modern education, overweighted with economics, may educate us to be good clerks; only a curriculum in the broad humanities can educate us to be good human beings. By harmonizing head and heart, Apollo and Dionysus, the Athenian classics train the complete man rather than the fragmentary man. With his onesided emotionalism or one-sided intellectualism, the fragmentary modernist sees life neither steadily nor whole. "Almost all we have of any real and lasting value," Alfred North Whitehead would say to his friends at Eliot House, "has come to us from Greece. We should be better had we kept a bit more. . . . Philosophy at its greatest is poetry and necessitates esthetic apprehension. "6 This esthetic apprehension is the first victim of any go-out-and-make-goodquick education. The splendidly unbusinesslike function of humanist education is defined in the 1948 report of the Commission on Liberal Education of the Association of American Colleges:

Our society is preoccupied with activities that obscure and in effect deny the importance of knowing and understanding letters. This unhappy situation arises partly from technology's promise of great physical comfort, partly from the material rewards most esteemed in a materialistic society, and partly from the dangers of our time that seem to demand immediate and material solution. Young people, therefore, take inordinate interest in what they think is practical study, failing to realize that self-knowledge, which is indispensable to the most practical judgments, is the highest practicality....

Literature arrests the rapid flow of experience, holds it up for contemplation and understanding.

In a period of technological prodigies and of economic complexity, the crucial problem of education is to sustain and develop the individual. If social and economic welfare are realized, we are told, the individual can take care of himself. It is at least equally true that if an adequate number of individuals are unusually elevated, society can take care of itself.

Education must be concerned both with man and society. Its purpose must be to create a community of persons, not a mere aggregation of people. The distinctive value of literature is that it enables one to share intensely and imaginatively the rich, varied experience of men of all ages who have been confronted with human problems and conditions of life common to men. It thereby leads to self-discovery and self-realization.

Does the humanist stress on the perfection of great creative individuals sound too aristocratic for an ant-heap age? Perhaps that is just how it ought to sound. We don't need a "century of the common man;" we have it already, and it has only produced the commonest man, the impersonal and irresponsible and uprooted mass-man. What we need, and what a humanistic, non-utilitarian education will foster, is a century of the individual man. Such a century would no longer change persons into masses but masses into persons, each with individuality and a sense of personal responsibility, each with a sense of his ethical duties to balance his material rights. Democracy, though slowly attained and never by revolutionary jumps, is the best government on earth when it tries to make all its citizens aristocrats. But not when it guillotines whoever is individual, superior, or just different.

In times of shallow prosperity, the conservative function is to insist on distinguishing value from price; wisdom from cleverness; happiness from hedonism; reverence from success-worship. In times of defeat, conservatism reminds us that we must still respect moral and social law, no matter how desperate our apparent crisis and no matter how radiant the ends that would "justify" our using lawless means. 'There are things a man must not do to save a nation," said John O'Leary to Yeats in a discussion of nationalism.7 Already in the fifth century before Christ, the historian Thucydides commented on the class struggle in Greece: "Men too often, in their revenge, set the example of doing away with those general laws to which all alike can look for salvation in adversity."8

The conservative lays the greatest possible stress on the necessity and sanctity of law. To him the "general laws," to which Thucydides referred, must be supreme over the particular ego of any individual or class or state. General ethics must restrict the particular means, regardless of ends. Let us suppose it were some day proved—as today alleged but unproved—that right and wrong are mere bourgeois prejudices of national or class interests and do not really exist. Instinctively we might say: so much the worse for right and wrong. Yet, even then, we should have to learn to say: so much the worse for existence. Sad experience would teach us that man can only maintain his existence through guiding it by the nonexistent: by the moral absolutes of the spirit. If this sounds paradoxical, it is of such paradoxes that human truth is made.

To rhapsodize over man's "natural, instinctive sense of justice," as opposed to established traditional legality, is a highbrow version of lynch law. Despite eloquent advocates of progressive education, the function of education is conservative: not to deify the child's "glorious self-expression" but to limit his instincts and behavior by unbreakable ethical habits. In his natural instincts, every modern baby is still born a caveman baby. What prevents today's baby from remaining a caveman is the conservative force of law and tradition, that slow accumulation of civilized habits separating us from the cave.

The accumulation is haphazard. As liberals correctly accuse, it includes much unfairness and much ignorance as well as good. When the bad is separable from the good, it is the conservative's as much as the liberal's duty to prune it. The dilemma on which liberals and conservatives split arises when the good and bad are inextricably interwoven by the centuries. He who irresponsibly incites revolutionary mob emotions against some minor abuse within a good tradition, may bring the whole house crashing down on his head and find himself back in the jungle—or its ethical equivalent, the police-state. You weaken the aura of all good laws every time you break a bad one—or every time you take a short cut around the "due process" of a good one. The lynching of the guilty is a subtler but no less deadly blow to civilization than the lynching of the innocent.

Conservatism belongs to society as a whole, for its purpose is to conserve the values needed by society as a whole. Conservatism is betrayed when it becomes the exclusive property of a single social or economic minority. This is the temptation every conservative faces, just as does every rebel on the other side of the fence. Many succumb. Many don't.

Sometimes the conservative orates too pompously about "maintaining established institutions." These can be discredited in two ways: by attack from the left or by exploitation from the right. When the conservative fails to save them from discredit, it may be the fault of the left. But it may also be his own fault for overemphasizing the attack from the left and underemphasizing the exploitation from the right.

Since the industrial revolution, conservatism is neither justifiable nor effective unless it has roots in the factories and trade unions. It was the Tories of the 1830s, like the seventh Earl of Shaftesbury, who fought for the factory laws to improve English working conditions. The laws were passed against the opposition of Whig industrialists and many Utilitarian liberals. And later Disraeli's Conservative Party, against the bourgeois opposition of Gladstone's laissezfaire Liberal Party, legalized and protected the long-persecuted trade unions and passed the workmen's social laws of the 1870s. This is why the English Liberal Party has now almost expired, leaving the Conservatives and Laborites as the new two-party system. When the urban industrial worker of England votes today—whether for Laborites or Conservatives, whichever he freely elects—it is because Disraeli in 1867 "dished the Whigs" by extending the franchise, which the 1832 Reform Bill of the Whigs had restricted to the wealthy middle classes.

Most needed by conservatism is this humane portion of the Disraeli tradition, not his inhumane and cheaply flamboyant imperialism. Nor is this need for humane reform, which ought to spring from a feeling of brotherhood, bought off by condescension (Lady Bountiful making Christmas bundles for the Honest Poor) or by expediency (throw the proletariat another bone to keep it from growling).

We may distinguish between English or Western conservatism, on the one hand, and the reactionary misuse of conservatism in Eastern Europe and often in Central Europe. English conservatism tends to be evolutionary. Eastern conservatism tends to follow the self-defeating rigidity of a Nicholas I, whose motto was "submit and obey." Even in the west, the static type of conservatism finds adherents whenever there is an irrational antiradical panic instead of a rational antiradical alertness. Examples of this are, at times, the political thought of de Bonald and de Maistre and the atmosphere of the French emigration, all of which too often influenced Metternich as much as Burke did. A Burkean conservative opposes tyranny from above as well as from below, George III as well as Robespierre. Abusers of the conservative function oppose lawlessness only when it comes from "Jacobins" and "Reds," words often used irresponsibly against anybody who disagrees.

Why has the British monarchy survived as a symbol of unity beyond all parties while the monarchies of Russia, Austria, and Germany were violently overthrown? Perhaps because England, like the Dutch, Belgian, and Scandinavian monarchies, made a special point of distinguishing between violent and lawful opposition. The East, above all the tsardom, could not conceive of such a seeming contradiction as "His Majesty's loyal opposition," a concept basic to the conservative way to freedom.

Lip service to evolution is not enough to prevent revolution. Because the conservative ideal means so much more than its caricature of hardened-arteriesplus-dividend-checks, its legalism and its traditional institutions are the gateway to reform. They must never be permitted to become the gate against reform. The conservative evolves change peacefully and gradually from above instead of by unhistorical haste or by mob methods from below. Metternich summarized the conservative's position toward social change in four words when he told the Tsar: "Stability is not immobility."9

In eighteenth-century England and ...