![]()

1

A Literary Famity on the Verge

Derry and Plymouth

Most lives are meant to be lost. At least any that are found have to be lost first. 1

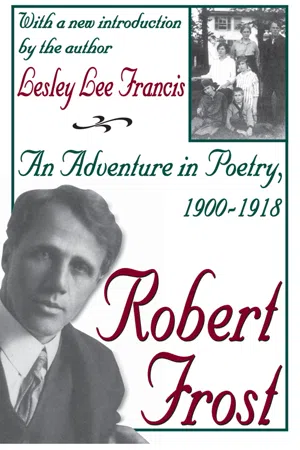

In revisiting the Derry years (1900–1911), capped by a year in Plymouth, New Hampshire, where Robert Frost taught at the Plymouth Normal School, I was able to identify the root cause of the Frost family's persistent nostalgia and homesickness while in England, as well as the root in experience that informs the poet's verses and distinguishes them from his fellow poets on both sides of the Atlantic. The contemporaneous record from the time in New Hampshire (flowing directly into the record for the English years) demonstrates, beyond any doubt, the inseparable, seamless nature of the Frost family's life in and of poetry until shortly after their return from England in 1915.

Living on the Derry farm in New Hampshire with her parents, my mother (Lesley)—together with her sisters (Irma and Marjorie) and brother (Carol)—received an “education by poetry.” “I learned,” she wrote in the introduction to the published facsimiles of her Derry journals, “that flower and star, bird and fruit and running water, tree and doe and sunset, are wonderful facts of life. The farm was enough of a world for learning.” She learned that the natural thing is always the adequate symbol, that the reality around her and the “imagination thing” are inseparable. Here is how she described the microcosm of the Frost children's world in 1908, at the age of eight:

journeys On The Farm

Our farm has interesting places to travel to, just like the world, though you do not have to journy so far as in the world. We go to some place almost every day that it is good enough to go and that is only when it is nice, but when it snows we sometimes dress up and go tramping out to the gate. When it shines we go every where on our farm though we have been there a hundred times.

The alders is one of my favorit places to go, because it reminds me of the brook that said “I sparkle out among the fern to bicker down the vally,” and the brook out there is just like it, though there isn't any fern, but it sparkles out among the woods to bicker down the vally. The next best journy I like is going over in the grove. That doesn't remind me of anything, but it is best to play in. You can make little houses and everything with the sticks and pineneedles that are over there and we go there very often, but we only go out in the alders once in three or four days.

The big pasture is my next favorite place because there is a little round grove out there of about six trees and they all touch together at the top and make a lovely shade to sit under as soon as it is warm enough and it is very comefortable. After the big pasture the field over across the road is next best. That is noted for it's checkerberrys. We go there almost every day to get checkerberrys or checkerberry leaves whatever we find there both just as good to us. All these places that I am speaking of we travel to about every day and play in each one half an hour and play that half an hour is half a year at some far off place in the world. April 9, 1908. 2

We know that all the Frost children “played school” and kept composition notebooks as part of their at-home education while living on the Derry farm, but that, from this period before the Frost family left for England in 1912, only Lesley's journals (published as New Hampshire's Child) have survived. It should be remembered, however, that the children's writings in England, mentioned earlier (Irma's “Many Storys,” Carol's “Our Old Farm,” Lesley's two untitled composition notebooks and “On the Road to Fleuraclea,” “An Important Year” by the four children, and, above all, the little magazine The Bouquet) nostalgically recall important aspects of life in Derry and Plymouth and contribute to our understanding of the family dynamics.

The children's notebooks and journals, and RF's own stories written for his children, show strong and pervasive parallels. RF's verses are analogous both in terms of their subject matter and stylistic development: daily life is mixed with elements of fantasy, the close and affectionate observation of nature, and an awareness of the precarious human condition and moral imperatives. Family values, in this context, are fostered in unorthodox ways, through a loose educational philosophy suggestive of Thoreau, Rousseau, or Montessori, with whose experimental approaches my grandparents were familiar. We will see, as well, the close parallels (and significant differences) with other literary families from this and earlier periods, with whom the Frosts also enjoyed at least a passing familiarity.

Two important areas in the poet's life are reflected in both the children's notebooks and in his own poetry from the Derry years: his teaching experience at Pinkerton Academy in Derry Village and at the Plymouth Normal School, on the one hand, and, on the other, his experience working the Derry farm and interacting with his family, now grown to six (Robert, Elinor, Lesley, Irma, Carol, and Marjorie). It would be his young audience, at school and at home, that helped shape RF's early verse, as becomes especially clear through a careful reading of the journals.

RF would have, in fact, a considerable body of verse (and some important pieces of prose) in the marketplace before the Frost family left for England. His poetic idiom had matured (as was evident already before leaving Harvard College in 1899 in his second year there), and he would carry with him most of the poems that were to appear in his first two volumes, A Boy's Will and North of Boston, published in London to favorable reviews and the beginning of public recognition both there and in America. He understood the strain between rhythm and meter and the importance of intonation, of mood and moment in creativity, of technical mastery. He understood the psychology of sound, and the images of sound conjured up through the imagination, as well as the sophistication and amplification of the proverbial turns of speech that already distinguished some verses in his first published poem, “My Butterfly: An Elegy,” which appeared on the front page of The Independent on November 8, 1894, a hundred years ago.

Too little attention has been given in the biography, I believe, to RF's growing confidence as a teacher and colleague prior to the family's departure for England, a downplaying explained, in part, by the absence of almost any reference to these experiences in letters or journals from this period. We know, however, that besides helping his mother in the classroom in Salem up to the time of her death in 1900, and employment as principal of the Shepard Evening School while at Harvard, he would come to devote more and more time to teaching and related activities than to “farming” as the Derry years progressed. Furthermore, while at the Pinkerton Academy in Derry Village, he was developing both a keen ear for dramatic speech and stage production and a greater ease in relating to his peers. We will see how the interest in dramatic dialogue is given full expression while in England.

Former students at the Pinkerton Academy and the Plymouth Normal School in New Hampshire provide a retrospective look at the poet and his family, reminding us of the maturity already achieved by 1911–1912. The author Meredith Reed remembers “a youngish-looking man with ruffled hair, deep-set blue eyes, and lips that looked as though they might be going to break into a smile—yet might not.” His eyes, which seemed to be looking straight at her, were “curiously amused and even more blue than I had thought.” She said she had never heard a voice like his, as when he read Shelley's “Ode to the West Wind”: “There was a sort of music to it, only music wasn't the word. It was light, like an open field; it was dark like mountain woods; sometimes it would break up into a lot of colors like glass hit by the sun; and sometimes it made you think of a violin when the strings were stretched too tight and tones jumped out from under the bow all rough and quivery-like.” 3 Margaret Abbott, who met her husband, John Bartlett, while they both were students at Pinkerton Academy, wrote that she was “carried aloft” by Robert's readings from Palgrave's Golden Treasury and other literature. Students considered him chummier with them than with the faculty: he skipped chapel, and he was interested in all sports and liked to hunt in the woods and fish in Beaver Lake. While still at Derry, he would invite the “boys down at his house for talks and games on Saturday mornings and it was always deemed a great pleasure to be invited.” He mingled with the students, playing football and “Ten Step.” 4

At the Plymouth Normal School, where Robert taught psychology and child growth and development, he was regarded as dreamy and soft-spoken, “wont to gaze into space and discourse more to himself than to the class.” His students found him exceptionally kind and gentle, someone who “always seemed to be [so] much interested in each of us as an individual that we soon felt … he was a real friend.” They were never bored in his classes because he always had ideas to present and was not confined to a text. When the Titanic sank (April 14–15, 1912), for example, the whole class was given over to discussing the newspaper accounts of the tragedy. He was easily distracted by stories about nature's creatures, and he would ask endless questions. He was enchanted when one of his students took him to see two bunnies hidden in the upper branches of a small hemlock, where she had fed them carrots and bits of apples. He was shy, the student observed, and she “could understand why his wife looked so adoringly at him and worked so hard for him.” 5

Elinor was well liked, too. At Derry, the other grangers helped her in many ways to prepare a small garden. “She did what little out-door work was done but she was unequal to it at that time having small children to care for.” The students enjoyed talking to her, and they admired her quiet concern for and devotion to her husband. At Plymouth, a student remembers spending “one of the pleasantest evenings” in the Frosts’ living room with a group of girls from the school. “I think it must have been before Christmas for the room was bright with decorations. A big fire in the fireplace, someone popping corn. Mrs. Frost, saying little, but making everyone comfortable and homey, and looking like a lovely madonna. The children were all there, quite young then and Mr. Frost entertained us with his stories and poems and just being himself.” Students got to know the Frost family well, it seems. On Mondays, the days the students were free instead of Saturdays, they would go together on “an all day's hike to Mt. Prospect with [their] lunches provided by the School. These were very pleasant times.”

Nine-year-old Irma Frost would recall in her “Many Storys” (Christmas 1912) climbing a mountain in Plymouth she couldn't remember the name of “with some of the nomole school grils.” They made their way to a spring for their picnic, and then went on up the mountain with the girls, while “Marjorie and mama did not go to the top.” One girl put a feather from her hat in “papa pocket when he didn't no it.” Elinor and her daughters got a ride home “in the otermobl … and we had a good supper.”

Robert may have been the only teacher at the time with a family, and the Frosts often came to the dining hall for their meals; on these occasions, he was, the students recall, “attentive in his manner toward his family and would listen to the children's prattle, occasionally breaking in with an amusing incident which would make the children giggle.” There were neighbors at Derry who thought Robert was a lazy farmer, which he was, and Mr. Silver, with whom the Frosts took lodgings in Plymouth while there on a one-year appointment, commented on the absence of routine in the Frost household. He remembered their late hours and the sight of the children going off to school, grabbing a bite of food left on the table from the previous evening.

Elinor did not talk about the past, and her tendency to silences may have dated from the death of her first son, Elliott, who died on the Derry farm from some type of influenza at the age of four in 1900. Although she and Rob exchanged harsh words at the time, they were never estranged. 6 She soon renounced any belief in a Supreme Being, distancing herself from her mother and oldest sister, Ada, who had become Christian Scientists; they had urged the Frosts not to call the doctor, who, when eventually summoned to the Derry farm, said it was too late to save the child. Elinor's sister Leona and her father, Edwin White, continued to visit the Frosts at the Derry farm, and her father died of a heart attack while at their home in Derry Village in 1909.

RF told family members that he had never written a poem without having Elinor in his thoughts. Every one of them, he said, pertained to her in some way. He also said she had the best ear for sound in poetry of anyone he ever knew: she would tell him when a vowel sound needed to be changed. Her daughter-in-law, Lillian LaBatt Frost, remembers Elinor as a quiet gentlewoman, whose silences disturbed her husband but seemed natural to her. She had a good sense of humor, with a sweet, shy giggle, Lillian recalls. She enjoyed reading and watching and listening to the evening card games, and she liked to play croquet. She made all the children's clothes when they were young, and she never thought of herself if there was RF or her children or grandchildren to think about. A college friend, from her St. Lawrence University days, agrees. She never thrust herself forward, he remembers; she was unassuming and unostentatious: “In other words, she was in no way a mixer. Her real life was an inner one. She was always and everywhere demure, quiet, contemplative, serious and thoughtful.” 7

Part of the reason for this distancing may have been Elinor's fragile health: she tired easily—perhaps because of a heart condition that gradually worsened as a result of childbirth and personal loss, perhaps because of a tendency to melancholia, we simply don't know. She found it difficult to complete household chores, which she detested, and she leaned on her more energetic husband and eldest daughter to pick up the pieces when she became ill. An editor of the family letters adds perceptively to this impression of Elinor and the pale reflection of this intelligent woman's inner life we find in her correspondence: “Elinor Frost—seldom as relaxed or revealing as Robert—is beside and a bit behind her husband in [her] letters, just as she was in life. No liberationist, however, should be too quick to misunderstand. She was no less opinionated than her husband, and their views frequently collided. Hers was an enormous influence—both in family matters and in the shaping of Frost's poetry.” 8 A growing sense of fatigue and sadness, as family tragedies mounted, would overshadow Elinor's final years, but that was a future no one in the Frost family could foresee in 1912.

Life and poetry were so intimately related at home, in fact, that only Elinor was fully cognizant of her husband's personal ambition. In her Derry journals, Lesley recalls that her father, “after exposing me to a variety of narrative and lyric poems (some of which I quickly learned by heart) and after getting me to write brief critical essays [in her journals by the age of seven] never so much as hinted that he was frequently writing poems of his own, at the table in the kitchen of our farmhouse, long after we children had gone to bed.”

9 Lesley summarized these roles in her introduction to the published journals:

It was to Mama we returned with full accounts of our adventures, adventures encountered on our own or out walking with Papa. The house was her castle, her province, and she was home. Going home from anywhere, at any time of day or night, meant returning to her. … By the time we had divided up the time of day, even the time of year, there was very little time left over to worry about. … Reading (by the age of four) and being read aloud to (until the age of fifteen!), I unconsciously heard the warp and woof of literature being woven into an indestructible fabric, its meaning always heightened by the two beloved voices going on and on into the night as a book was passed from hand to hand. We children could linger to listen until we were sleepy, however lat...