Corporate Social Responsibility for Sustainable Tourism

- 270 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

Corporate Social Responsibility for Sustainable Tourism

About This Book

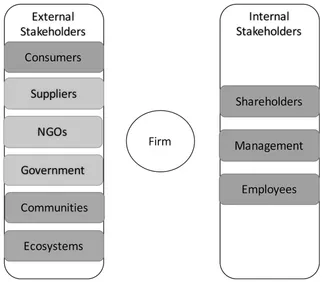

This comprehensive volume considers the corporate social responsibility (CSR) of tourism and hospitality firms towards stakeholders, exploring CSR in terms of broad stakeholder accountability by considering both the scope of reporting and the quality of stakeholder engagement. The authors analyse how CSR contributes to shareholder accountability (i.e. as financial performance) by developing a multiple attribute decision-making model to deploy CSR resources, analysing how CSR contributes to the management of systematic risk as part of an internationalisation strategy, and showing how philanthropy is used as a legitimisation tool.

The authors then review how managers negotiate CSR priorities within their organisational strategy by accounting for the utility gained by family firms from ecological and social outcomes in comparison with profit outcomes, analysing the trade-offs of co-constructing a sustainability innovation and weighting factors in water planning. They also review how employees are central to the delivery of CSR actions by exploring how green organisational culture affects organisational citizenship behaviour, how organisational green practices impact an organisation's image and its customers' environmental consciousness and behavioural intentions, and how organisational CSR affects employee pro-environmental citizenship and tourists' pro-environmental citizenship. The book concludes by reviewing the role of consumers in CSR with ten strategies to close the consumers' attitude-behaviour gap and an account of how customers' trust is a mediator between CSR, image and loyalty.

This book was originally published as a special issue of the Journal of Sustainable Tourism.

Frequently asked questions

Corporate social responsibility in tourism and hospitality

Introduction

Overview of the literature

Society: stakeholder accountability

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- Citation Information

- Notes on Contributors

- 1 Corporate social responsibility in tourism and hospitality

- 2 The boundary of corporate social responsibility reporting: the case of the airline industry

- 3 The process of sustainability reporting in international hotel groups: an analysis of stakeholder inclusiveness, materiality and responsiveness

- 4 An assessment model of corporate social responsibility practice in the tourism industry

- 5 Internationalization and corporate social responsibility in the restaurant industry: risk perspective

- 6 The corporate philanthropy and legitimacy strategy of tourism firms: a community perspective

- 7 Green organizational climates and employee pro-environmental behaviour in the hotel industry

- 8 Customer responses to environmentally certified hotels: the moderating effect of environmental consciousness on the formation of behavioral intentions

- 9 Activating tourists' citizenship behavior for the environment: the roles of CSR and frontline employees' citizenship behavior for the environment

- 10 Trade-offs between dimensions of sustainability: exploratory evidence from family firms in rural tourism regions

- 11 Eco-innovation for sustainable tourism transitions as a process of collaborative co-production: the case of a carbon management calculator for the Dutch travel industry

- 12 Influential factors in water planning for sustainable tourism destinations

- 13 All aboard! Strategies for engaging guests in corporate responsibility programmes

- 14 Trust as mediator of corporate social responsibility, image and loyalty in the hotel sector

- Index