In this article, the author presents research that explores individual and collective autobiographical acts aiming at the creation of places of enunciation for decolonial selves through practices in the visual arts. This practice-based research benefits from interdisciplinary crossings between feminist geography, life writing, and decoloniality, through which the author designed the network of concepts that gave form to the epistemological approach to practice and research used. The first stage of the practice is a self-reflective response to personal experiences within geographical displacement and dislocation in language. The second part comprises collective writing processes conducted with twelve Brazilian women who live in London. Writing is a cross-element in this practice-based research, and visual arts offer a space for exploring decolonial acts. Thus, the author sought in decoloniality a path to offer a contribution to knowledge by proposing decolonial strategies for writing life narratives within displacement through translanguaging and autobiogeography.

A few months before starting my doctoral research project at the Chelsea College of Arts, I came across a remarkable traffic sign in London (Figure 1). Its text warned “Diversion Ends,” but someone had accented the word “Diversion,” scratched out the word “Ends,” and answered in Spanish, “La Diversión Ha Empezado!!!” (“The Fun Has Begun!!!”).

This traffic sign shows how powerful an acute accent can become: it converted English into Spanish, opened the public space for a different dialogue, and gave place to another language, tone, meaning, author, and readers. This accent turned a space for warning into a place for diversión, diversidad, diversidade, diversity. All these words are related to the Latin verb vertere, which means “to turn” and can be translated into Brazilian Portuguese as desviar, “to divert,” or mudar de posição, “to change position.” When I first read this message, I immediately felt I was being addressed and I was brought out of the place of muteness I entered when I became a newcomer in London with difficulties in communicating in the English language. I noticed that “turning” could become a powerful strategy for creating places where other presences, voices, meanings, and stories can coexist. At that moment, I understood that belonging, in the context of immigration, can be directly related to being addressed and invited to a conversation that is conducted in a “pluriversal” environment where languages and cultures are not only related to each other, but also entangled among themselves (Mignolo, “Pluriversality”).

My project found its starting point in the middle of personal changes in geography, language, self, and identity. It branches into myriad fragmented stories written in-between languages through my practice in the visual arts and is inspired by life-writing genres such as diary, memoir, and correspondence. While I invented forms to express myself in English and write my own stories about displacement in this language, I also unfolded artistic methods for knowing other Brazilian women’s stories. In this process, art practice helped me to reach higher levels of consciousness about my subject positions as a woman who came from central-western Brazil to study in London. Such awareness led me to reflect in more depth on power relations between language and place, and their impact on my self-perception and agency.

The objective of my investigation is to understand how practices in the visual arts can engender individual and collective decolonial acts for exploring experiences of displacement, raising an “immigrant consciousness” (Mignolo, “Geopolitics” 132–33), and opening places of “enunciation” for decolonial selves (Gaztambide-Fernández 198–200). For the purposes of this project, I employ Walter Mignolo’s approach to decoloniality, since it highlights “attitudes, projects, goals, and efforts to delink from the promises of modernity and the un-human conditions created by coloniality” (“Further” 27), stimulating critical analysis of “the construction, transformation, and sustenance of racism and patriarchy that created the conditions to build and control a structure of knowledge” (Darker xv).

Therefore, my research topic emerged from my own experience as a newcomer in London who entered a place of muteness after being challenged by a new language in a new place. Although I became mute, I refused to be silenced by the coloniality of being, sensing, and knowing that was operating in my subjectivity, and decided to face the shame of not knowing the language through creating strategies for “turning” the place of muteness into a place of enunciation. Thus, with|in silence but not silenced, I experimented with decolonial acts through my practice in the visual arts to articulate life stories and reinvent my voice by critically positioning myself in the middle of my own muteness. This experience led me to coin the idea of “autobiogeography as decolonial methodology” (“Autobiogeografia”), which stimulates the creation of situated autobiographical acts through art practice to confront the coloniality of power and raise an immigrant consciousness. This experience changed my practice as an artist: now, rather than creating artworks, I first want “to create in order to decolonize sensibilities” (Gaztambide-Fernández 201) and open paths toward my decolonial self.

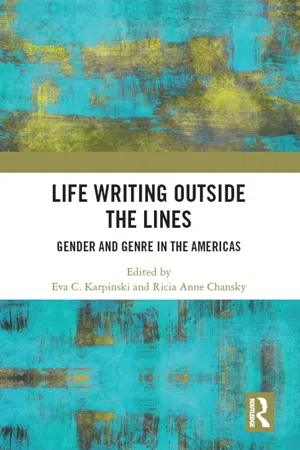

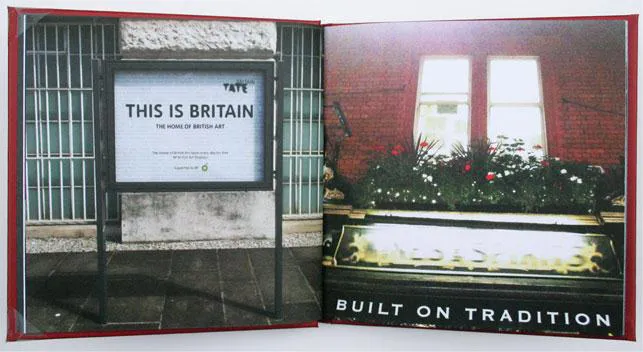

Inspired by the traffic sign (Figure 1), I developed a writing process that consists of assembling photographs of words collected in the city into artist’s books. In this article, I present the first pair of books created by using “turning” as a mechanism for changing the meaning of words and writing personal narratives. It is called “Memoir (London, 2010–2013)” and comprises two books: a red book (Figures 2 and 3) and a black book (which will be shown later in this text).

The photographs used to write the red book were taken during my first walks on the streets of London. Differing from the other books produced afterwards, in “Memoir (London, 2010–2013)” I was not conscious that I was collecting words in the city. I only realized this fact when I decided to apply for a doctoral degree and needed to look back carefully at my visual work to design my art-based research project. I was surprised by my own collection of words because it perfectly addressed my experiences as an immigrant living in London. By looking at and reading my photographs, I realized that my feelings of unease were directly connected to the messages I was receiving from the city, which constantly reminded me that I did not belong there (Figure 2). Then, I framed my research project on the relationship between language and place, and decided to start by investigating which stories were hidden in the words that I had collected. When I realized that the hidden stories were about the colonial traces in my own being, I answered to|through the city, with|in silence: “Remember Me | We Are Here to Create Purpose for Life” (Figure 3).

Writing by combining images to unveil the coloniality of being, sensing, and knowing became a key element for my art practice in this project. In this process, photography came to work as a kind of “type machine,” through which I “wrote” words by clicking—that is, by photographing them on the streets (Figure 4).

As I started to position myself as a writer, I sought to find a life-writing genre that could be in dialogue with what I was doing with the images of words in my artist’s books. Language memoir (Kaplan) seemed to be the perfect genre to guide conceptually this writing-making process, since it focuses on the experiences about learning a language. In addition, as G. Thomas Couser reminds us, memoir is a relational and democratic life-writing genre rooted in the ways people represent their lives, make identity claims, and locate themselves through personal stories connected to everyday life. Rather than registering preexisting selfhood, memoir nurtures processes that bring new selves into being and “has been a threshold genre in which some previously silent populations have been given voice for the first time” (Couser 12).

Writing about crossings from one language to another, and thus from one culture to another, highlights the problem Mignolo pointed out by regarding the complicities between language and the notions of empire and nation. Mignolo argues, “While the imaginary of the modern world system focused on frontiers, structures, and the nation-state as a space within frontiers with a national language, languaging and bilanguaging, as a condition of border thinking from the decolonial difference, open up to a postnational imaginary” (Local 253). From the colonial perspective, translation is rooted in the principles of epistemic colonial power and might work as a tool to stress colonial difference, which tends to racialize people and make them “seen as inferior by the dominant discourse” (Darker 214). This is a kind of translation that leads to conversion instead of conversation, reinforcing “the colonial difference between Western European languages (languages of the sciences, knowledge, and the locus of enunciation) and the rest of the languages on the planet (languages of culture and religion and the locus of the enunciated)” (Mignolo and Schiwy 10).

In my case, the hierarchy between languages can be felt in two ways: from the Brazilian Portuguese to the Portuguese language, and from the Brazilian Portuguese and its accent to the British English language. The former is related to my own family history, since I was born to a Portuguese father and a Brazilian mother, who does not know very much about her own Indigenous heritage. The latter refers to my experience of learning British English in the UK, where different levels of prejudice are connected to the different types of accent that people in this country have. In the first case, I experienced linguistic prejudice when I first traveled to Portugal to get to know my family on my father’s side. There, I was told that what we speak in Brazil is not Portuguese at all: it is “Brazilian.” Curiously, in London I heard the same story: in the US, people speak “American,” not English. In the second case, while I lived in London, I discovered that learning “standard English” would not be enough because, in British society, there is discrimination against people because of their accent (Figure 5). It became clear that there is a hierarchy between not only western and non-western languages, but also between western languages and the languages that are a legacy of colonization, such as the Brazilian Portuguese and the American English languages.

In the Zapatista movement, for example, another kind of relationship between languages emerges: the “double translation” (Mignolo and Schiwy 17–20), which differs from the one-way translation process implied by the modern colonial world system based on metropolitan interests. Thus, the Zapatistas’ theory of translation is conceived as a re-educational process called “translanguaging,” which is “a way of speaking, talking, and thinking in between languages” (27). Therefore, as another option, translanguaging offers places for border thinking where new perspectives to conceptualize translation and transculturation can be built through the “double consciousness of subalterns in confrontation with hegemony” (22). In this way, translanguaging “turns” hegemonic languages into tools for communication, connection, struggle, justice, and transformation.

In my practice, I used “turning” as a decolonial act for creating translanguaging possibilities through writing with images of words collected in the city. This process helped me to reposition my voice and self in order to transform a place of muteness into a place of enunciation. Through “turning,” I activated voice with|in silence and became aware of the traces of coloniality operating in my own being|sensing|thinking. As Mignolo argues, in the decolonial option, one must “engage in epistemic disobedience” if one intends “to take on civil disobedience,” because only in this way is it possible to go beyond reforms and provoke transformations (Darker 139). This kind of disobedience demands a decolonial courage to confront coloniality and deal with the colonial wound (Figure 6). In order to heal the colonial wound, one needs to create processes of delinking for “regaining your pride, your dignity, assuming your entire humanity in front of an unhuman being that makes you believe you were abnormal, lesser, that you lack something. How do you heal that? Through knowing, understanding, decolonial artistic creativity and decolonial philosophical aest...