![]()

1

The defeat

Nazi Germany invaded France on 10 May 1940. On 25 June, with the French army and the British Expeditionary Force (BEF) routed, Paris and Berlin declared a ceasefire. The fighting had lasted six weeks yet, in truth, the battle was lost in a matter of days. Hitler and his army commanders had fooled the Allies into believing that the main thrust of the German advance would come from the north through Belgium. In fact, the Nazi spearhead struck further south in the relatively poorly defended Ardennes region. Britain and France realized their error too late. By 15 May, with German forces having broken through French lines, Prime Minister Paul Reynaud informed his British counterpart Winston Churchill: ‘we are beaten; we have lost the battle’.1 The Wehrmacht soon encircled Allied forces. The evacuation from Dunkirk averted catastrophe for the British but the French were not so fortunate. On 17 June, Marshal Philippe Pétain, successor to Reynaud as Prime Minister, announced that he would seek an end to hostilities with Germany. On 25 June, fighting ended. French writer Jean Guéhenno recorded the moment in his diary: ‘The bells for the “Ceasefire” rang at midnight. I had not realized that I loved my country so much. I am full of pain, anger, and shame’.2 France was beaten.

The rapidity of the Allied collapse stunned the world. Historian Nicole Jordan has described the defeat as ‘one of the great military catastrophes in world history’.3 In Washington, President Franklin Roosevelt endured sleepless nights as he pondered the seemingly inevitable invasion of Britain. In Moscow, Stalin raged at the French capitulation, sensing Hitler’s gaze now upon the Soviet Union. Marc Bloch, a French medieval historian who had fought in the battle of 1940, turned his fire on society, attributing the disaster to a long-term rot present from top to bottom.4 American journalist William Shirer likewise perceived deep causes to the so-called ‘débâcle’ (rout). The French had had, ‘no will to fight, even when their soil was invaded’. The defeat amounted to no less than ‘a complete collapse of French society and of the French soul’.5

Until the late 1970s, historians of the defeat tended to take their lead from such contemporaneous accounts. Jean-Baptiste Duroselle’s hugely influential 1979 book on interwar French foreign relations – damningly entitled La décadence (in English, decline) – blamed a political class unable to mount an effective response to foreign threats.6 The French public seemed to agree. An opinion poll in Le Figaro Magazine in 1980 found that more than half of respondents blamed the Third Republic for the catastrophe.7 A second school of thought has since contested this view, preferring to focus on the immediate military factors behind the defeat rather than looking for long-term causes in French society. In his 2003 The Fall of France, by far the best text on the subject, Julian Jackson concluded that ‘[t]he defeat of France was first and foremost a military defeat – so rapid and so total that … [long-term] factors did not have time to come into play’.8 France lost the fight on the battlefield not in the bitter divisions of the interwar years.

This chapter investigates the defeat of France in 1940. Firstly, it examines the causes of the French collapse and debunks some of the myths regarding the country’s preparedness for war. It recognizes, too, that the catastrophe of 1940 was an Allied defeat. While the bulk of forces engaged in the battle were French, the BEF and the RAF also fought to hold back the invader. The Allied Supreme War Council co-ordinated French and British economic and military planning for the conflict with Germany. London and Paris approved the strategy that would eventually undo the Allies’ campaign. Secondly, the chapter explores the repercussions of the war in Europe in the territories of the French Empire. Between 1939 and the Armistice of June 1940, over 600,000 troops were recruited from French African and Asian territories.9 The deaths of thousands of these troops and the imprisonment of many more had an impact on communities around the world. Finally, the plight of men and women far from the battlefield comes under consideration. Eight million civilians from northeast France and the Low Countries fled their home to escape the advancing German army. Life on the road during the ‘Exode’ (Exodus) was tough: food and water were scarce, families experienced separation, and the threat of attack from German planes was constant. The Battle of France was not only a military and political disaster but also a human one.

The Battle of France

The German invasion of Western Europe began on 9 May 1940 with attacks on Belgium, Luxembourg and the Netherlands. Supreme Allied commander General Maurice Gamelin – under whose authority lay the French military and the BEF – immediately implemented ‘Plan D’ to defend French territory. This so-called ‘Dyle manoeuvre’ entailed an eastward push into northern Belgium by the very best French and British forces. These crack troops would obstruct the German advance at the rivers Dyle and Escaut in Belgium. The Allies planned to fight the conflict with Germany on Belgian soil, sparing France the destruction that it had experienced during the First World War.

With Allied minds concentrated on obstructing the invasion in Belgium, German eyes turned to the Ardennes, a region spread across Luxembourg, southern Belgium and northeast France. Allied commanders believed that this hilly and forested terrain presented a natural barrier to the invader. They dismissed reports of columns of German vehicles moving in this direction as alarmist.10 In any case, the Allies estimated that it would take ten days for an army to break through the Ardennes; in fact, it took German soldiers only sixty hours.11 The German move into northern Belgium was a feint, a ‘matador’s cloak’. Further south, four columns of tanks and motorized vehicles, each stretching back over 400 kilometres, advanced towards the river Meuse. With the element of surprise paramount, the Wehrmacht progressed for three days and nights without a break, their drivers dosed with the amphetamine Pervitin.12

The German army encountered little resistance before reaching the strategically important Meuse river. This was the weak point of French defences. The vanguard of the invasion, General Ewald von Kleist’s group, comprised 134,000 troops, 1,200 tanks and 1,000 aircraft. In total, forty-five German divisions faced nine-and-a-half French, made up mainly of reservists in poor shape with inadequate equipment.13 Strength of numbers and the massive aerial bombardment of French positions ensured that German troops were able to cross the river at Sedan, Houx and Monthermé. Only on the night of 13 May, with the Germans having crossed the Meuse, did the Allies realize that the real invasion was underway in the south.

The dispersal of French forces and the unpreparedness for an attack on the Ardennes saw the disintegration of Allied defences. During the night of 16 May, Panzer Commander Erwin Rommel’s division managed to advance more than 100 kilometres into French territory. The following day, Gamelin’s order to his soldiers – ‘CONQUER OR DIE. WE MUST CONQUER’ – came too late; Reynaud replaced him with General Maxime Weygand on 18 May.14 Three days later, German forces reached Abbéville on the shores of the English Channel. Nearly 2 million French, British, Dutch and Belgian soldiers were caught in ‘the largest encirclement in military history’.15 Allied strategists considered a joint attack to cut the head off the German advance and break out of their encirclement (the so-called ‘Weygand Plan’). However, by 25 May French and British leaders ordered a retreat to the coastal town of Dunkirk. The next day, Operation Dynamo was launched to evacuate Allied forces from the continent.

When on 3 June German bombs fell on Paris, the government of the Third Republic decided to move from the capital. A week later, the City of Light was declared ‘open’; it would not be defended street-by-street as Churchill had urged. Prime Minister Reynaud, his cabinet, and President Albert Lebrun travelled south to the chateaus of the Loire valley. At a meeting on 12 June, with the Germans in Paris and France at war with Italy since 10 June, Weygand proposed an armistice. On 13 June, Pétain threw his weight behind Weygand’s proposal: ‘The armistice is in my eyes the necessary condition of the durability of eternal France’.16 Reynaud hesitated, considering the possibility of continuing the fight in exile from North Africa. A further meeting on 15 June, this time in Bordeaux, saw the armistice faction strengthened. Roosevelt had telegrammed his sympathy for the French predicament but Washington had offered no practical support. British pleas that the French continue the fight were ignored. On 16 June, with his options dwindling in the face of strengthening defeatist sentiment amongst his ministers, Reynaud resigned. Pétain took over as premier. The next day, the eighty-four-year-old Marshal spoke on the radio: ‘It is with heavy heart that I say to you today that it is necessary to cease fighting’.17

In order to understand why the French cabinet ultimately swung behind an Armistice, leaving Reynaud with few other options but to resign, we must examine reshuffles that took place during May and June 1940. Between 17 and 19 May, Reynaud brought Weygand and Pétain into the cabinet, along with the Republican Georges Mandel. Reynaud intended to appoint Weygand head of the armed forces yet in doing so he had brought into government a reactionary man who was certainly no lover of democracy. Pétain’s politics were less clear yet by 26 May the Marshal was already looking to shift the blame for the disastrous situation away from the army, telling an acquaintance, ‘The real guilty party is premier Daladier’.18 On 5 June, Reynaud dismissed Edouard Daladier from the foreign ministry in a move that was likely designed to eliminate a personal rival but in fact removed a man in favour of continuing the war effort, too. At the same time, Reynaud appointed Paul Baudoin, Yves Bouthillier and Jean Prouvost to cabinet positions on the advice of his mistress Hélène de Portes. Baudoin and Bouthillier were close to the extreme right while all three men, like de Portes, were defeatists. The deterioration of the situation on the battlefield continued to strengthen the pro-armistice faction, turning their minds not just to the negotiation of a ceasefire but also to a change of regime; ‘This country needs an overhaul top to bottom’, argued Pétain. Reynaud’s isolation in government grew. When, on 16 June, the Marshal threatened to resign if the government did not immediately seek peace terms with Berlin, the Prime Minister threw in the towel.19

Armistice negotiations began on 21 June at Rethondes, in the forest of Compiègne. This location was highly symbolic: it was the exact spot where Germany had agreed to the Armistice in 1918. Hitler’s dark sense of theatricality did not end there. The Fuhrer had ordered that the French sign the surrender in the very same railway carriage as the German capitulation twenty-two years ago. Filmed for posterity, it is today difficult to view the humiliated French delegation arrive to be greeted by the Nazi leadership. Shirer noted that Hitler’s face was one of ‘revengeful, triumphant hate’. The French representatives – General Huntziger, Air General Bergeret, Vice-Admiral Le Luc and M. Noël, French Ambassador to Poland – were ‘the picture of tragic dignity’.20

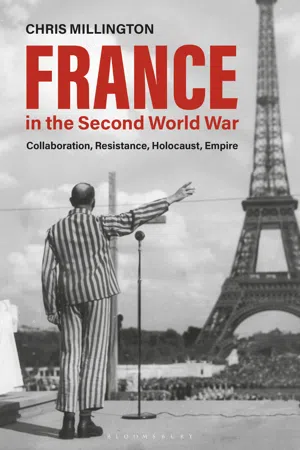

Figure 1 The Nazi leadership, including Hitler, Goering, Joachim Von Ribbentropp and Marshal Keitel at Rethondes, 22 June 1940. Photo by Keystone-France/Gamma-Keystone via Getty Images.

The Armistice provided for the occupation of three-fifths of France by German troops, the delivery of all military material to the Wehrmacht, and the confinement to port of the navy.21 It imposed a crushing financial penalty on the defeated French, who would be forced to pay the costs of their own occupation. Other significant articles included the obligation that all German nationals in France surrender to the authorities. Many of these people had fled to France to escape persecution during the 1930s. Article Twenty required that all French prisoners of war (POWs) remain captive in Germany until the conclusion of a formal peace treaty. These POWs were used as a bargaining chip throughout the Occupation. Italy ...