![]()

one

THE INDIAN WEST AT MIDCENTURY

ON AUGUST 29, 1846, a party of Cheyenne Indians pitched their conical skin tipis on the north bank of the Arkansas River near the bastioned adobe castle where the Bent brothers had traded since 1833. Among the party was Yellow Wolf. A hardened, wiry little man in his middle sixties, Yellow Wolf enjoyed an enviable record as a leader in warfare with the Kiowas, Comanches, Utes, and Pawnees, and as a chief of the prestigious Dog Soldier band he exerted great influence in his tribe. Few Cheyennes possessed his wisdom or intellect. It was Yellow Wolf who had persuaded “Little White Man” William Bent and his brothers not to locate their trading post farther up the river, beyond the buffalo range. Ever since, Yellow Wolf and his people had been the Bents’ staunchest supporters among the southern Plains tribes, an affinity cemented when William Bent took a Cheyenne wife, Owl Woman.

Yellow Wolf reached Bent's Fort in time to witness the closing scenes of a momentous summer. Beginning in late July, the valley around the fort had begun to fill with white men. The tents of seventeen hundred soldiers sprouted for miles along the river. Rank on rank of white-topped wagons drew up nearby. Twenty thousand horses, mules, and oxen covered the sandy plain. The soldiers were marching to fight the Mexicans, they told the Indians gathered at the fort to trade. In wonder, they declared over and over that they had never supposed there were so many white people.

Most of the army had moved on by the time Yellow Wolf arrived, but the spectacle of its passage may well have crystallized his thinking. He had noted year after year the growing presence of white people in the Indian country. Each year more wagons made their way across the plains with goods for trade with the Mexicans in Santa Fe. The signs were ominous, and they pointed to a conclusion no other Cheyenne leader was to acknowledge for years. He shared his thoughts with an army officer recuperating from an illness at Bent's Fort. Yellow Wolf, the officer wrote in his journal,

is a man of considerable influence, of enlarged views, and gifted with more foresight than any other man in his tribe. He frequently talks of the diminishing numbers of his people, and the decrease of the once abundant buffalo. He says that in a few years they will become extinct; and unless the Indians wish to pass away also, they will have to adopt the habits of the white people, using such measures to produce subsistence as will render them independent of the precarious reliance afforded by the game.1

Yellow Wolf had a good reason for apprehension. The march of these soldiers held great portent for the Cheyennes. This year of 1846 was one of profound significance, a year of decision. The army the Indians watched marching on the Santa Fe Trail—General Stephen Watts Kearny's Army of the West—was an instrument of decision. In the Mexican War of 1846–48 the United States seized the Southwest and California. Already, in 1845, Texas had been annexed; and on the eve of the war the resolution of the Oregon boundary dispute with Great Britain added the Pacific Northwest. With breathtaking suddenness, the United States flung its western boundary to the Pacific and transformed itself into a continental nation. Then, as if to light a powder train laid down by these events, on January 24, 1848, only ten days before diplomats at Guadalupe Hidalgo signed the treaty ending the Mexican War, James Marshall spotted a golden glint in the millrace of a sawmill he was building on California's American River. Territorial expansion combined with the discovery of gold to place the Indian world of the Trans-Mississippi West on the threshold of enormous change.

For Yellow Wolf and his people, the march of Kearny's army marked the end of one era and the beginning of another. In his remaining eighteen years the old chief saw his fears realized. He continued to believe that the only hope for his people lay in learning the ways of the white people. In the frigid dawn of November 29, 1864, the crash of carbine fire awakened him. With others of Black Kettle's village, he sprang from his tipi to confront the charging soldiers. And there on Sand Creek, not far from the melting mud ruins of William Bent's long-abandoned trading post, Yellow Wolf died, cut down in his eighty-fifth year by a bullet fired by a white man.

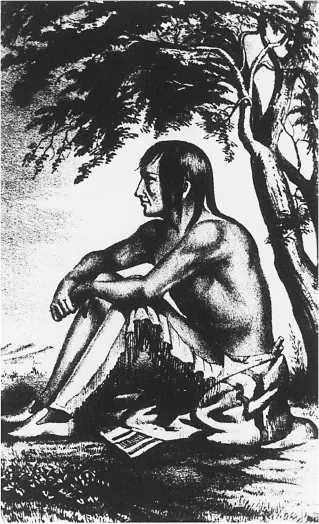

Fig. 1: Yellow Wolf. This prescient Cheyenne chief shared his fears for the future of his people with Lt. J. W. Abert at Bent's Fort in 1846, and Abert, impressed with the Indian's character and intellect, prepared this sketch for later inclusion in his official report. Puzzlingly, although already in his sixties, Abert gave him a decidedly youthful aspect. Without success, Yellow Wolf tried to persuade his people that their only hope of survival lay in adopting the ways of the white people. Whites repaid him with a bullet at Sand Creek in 1864.

The sudden leap of the nation's boundaries to the Pacific set off a process of confrontation and conflict between whites and the Indians of the Trans-Mississippi West. It was a process even then ending in catastrophe for the tribes of the eastern woodlands. Having destroyed one “Indian barrier,” an aggressively westering America now faced another. In less than half a century this barrier too would be destroyed, and white civilization would reign unchallenged over the plains, mountains, and deserts of the Trans-Mississippi West.

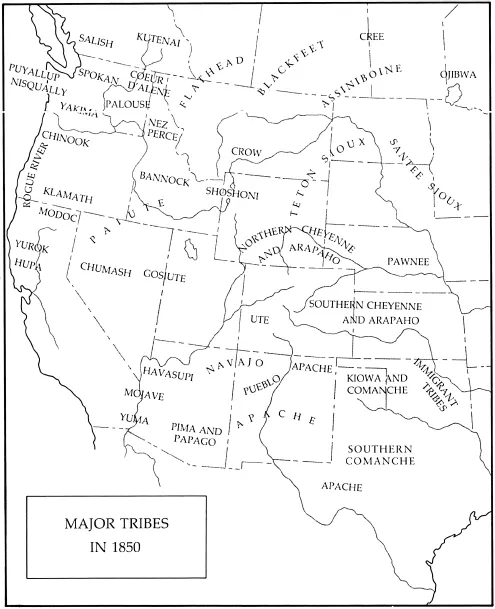

At midcentury the prospective victims numbered about 360,000.2 Seventy-five thousand ranged the Great Plains from Texas to the British possessions in buffalo-hunting nomads that have produced today's befeathered stereotype of the American Indian: Blackfeet, Assiniboine, Sioux, Cheyenne, Arapaho, Crow, Shoshoni, Kiowa, and Comanche, to name the most powerful. The nomads of the southern Plains shared their domain uneasily with some 84,000 Indians uprooted from their eastern homes by the U.S. government and swept westward to new lands beyond the ninety-fifth meridian. Most gave allegiance to what the whites, with unconscious patronization, labeled the Five Civilized Tribes: Cherokee, Choctaw, Chickasaw, Creek, and Seminole. Of the 200,000 Indians in the new U.S. territories, Texas claimed 25,000, most prominently Lipan, Apache, and Comanche. The Mexican Cession (California and New Mexico) contained 150,000, among them Ute, Pueblo, Navajo, Apache, Yavapai, Paiute, Yuma, Mojave, Modoc, and a host of tiny coastal groups that, whether or not wholly missionized, came to be known collectively as “Mission Indians.” The Oregon Country (later to give birth to the states of Oregon, Washington, and Idaho) was home to 25,000 Indians, including Nez Perce, Flathead, Coeur d'Alene, Spokane, Pend d'Oreille, Yakima, Walla Walla, Cayuse, Umatilla, Palouse, Chinook, Squaxon, Nisqually, and Puyallup.

Opposed to these Indians, the United States at midcentury boasted a population of more than 20 million, a counting utterly beyond the comprehension of the western natives. By 1860, 1.4 million would live in the West; by 1890, 8.5 million.

Although a so-called Indian barrier influenced the speed and direction of the white people's westward movement, it was scarcely a monolithic barrier. For four and a half centuries Europeans had applied the label “Indian” to the indigenous peoples of the Western Hemisphere, but this arbitrary collectivization obscured a profound diversity. Despite cultural similarities, the native Americans were in fact many different peoples. Thus no group typifies the western Indians. The Nez Perce affords as useful a group as any for suggesting who these people were that unknowingly, or with the vague forebodings of a Yellow Wolf, stood on the threshold of catastrophe.3

The Nez Perces were a handsome people of three thousand or less in 1850. They occupied the eastern reaches of the recently disputed Oregon Country—from the rugged, forested mountains drained by the Clearwater and Salmon rivers to the high, open plateaus gashed by the Snake and Grande Ronde rivers and bounded on the west by the Great Bend of the Columbia. They formed a bridge between the powerful buffalo-hunting plainsmen to the east and the small, loosely organized fishing groups to the west. Not surprisingly, their culture partook of both. They lived in skin or brush lodges and dressed in finely tailored skin garments decorated with shells, elk teeth, beads, and other ornaments. “Lofty eligantly formed active and durable” horses, in Meriwether Lewis's words, furnished transportation and the origins of the distinctive Appaloosa breed.

A ceaseless quest for food ordered the life of the Nez Perces. They planted no crops but moved about to where food could be had. In early summer, hillal, “the time of the first run of the salmon,” the people appeared on the banks of the rivers to spear or net salmon from the hordes fighting their way upstream to spawn. They gorged on fresh fish while drying and smoking supplies for leaner times. As summer warmed the meadows and prairies, the bands came together at favorite camas grounds for festival-like gatherings in which fun and visiting alternated with digging the onionlike camas root, a staple food of the tribe. Spring was also a time of harvest, when other roots and wild plants ripened. Throughout the year hunting engaged the men, as with powerful bow fashioned of mountain sheep horn they stalked elk, deer, mountain sheep, and bear, and with snare or net they captured rabbits and grouse. Each autumn some bands on the east trekked across the great rampart of the Bitterroot Mountains to chase buffalo on the plains of Montana.4

In addition to hunting and gathering, trade was an important element of the Nez Perce economy. They traded constantly with neighbors and periodically gathered at popular centers to meet more distant people. An annual truce in the warfare between the Nez Perces and their southern neighbors, Shoshonis and Paiutes, permitted a short period of trade. The Nez Perces’ most important trade, however, occurred at the fixed fishing villages of the Wishram, Wasco, and Wyampam Indians at The Dalles of the Columbia. Here Nez Perces met with Chinookan-speaking coastal peoples to exchange dried meat, furs, hides, roots, bear claws, and elk teeth for dried clams, fish oil, baskets, carved wooden implements, and dentalium shells. Equally significant, the barterers exchanged techniques, skills, and methods as well as legends, traditions, and lore that subtly but strongly reshaped intangible aspects of their cultures.

Living in intimate and precarious equilibrium with the environment, the Nez Perces pursued a spiritual life given form by nature and the individual's relations with nature. The land, especially their homeland, compelled a worshipful, mystical veneration. “The earth is part of my body,” declared old Toohoolhoolzote. “I belong to the land out of which I came. The earth is my mother.”5 Every feature of it, animate and inanimate, contained unseen spirits that formed a fellowship of which the Nez Perces were part and to which they looked for that ingredient most essential to progress through life—power. Almost every man and woman had a Wyakin—an eagle, a rock, thunder, a cloud—with which an intimate, personal, spiritual relationship was established and from which assistance and protection—power—could be drawn. “It is this way,” Many Wounds explained. “You have faith, and ask maybe some saint to help with something where you are probably stalled. It is the same way climbing a mountain. You ask Wyakin to help you.”6 An elaborate body of belief and practice, undergirded by a rich mythology, governed war and the hunt and political, social, and family relationships. Holy men worked miracles, aided healing, and advised in spiritual matters, but religion was still an intensely personal matter, involving the individual's Wyakin and all the phenomena of nature.

The Nez Perce accorded loyalty and allegiance first to family, then to band, and finally to tribe, but rarely beyond. These institutions provided the framework for the political system. It was a policy- and decision-making mechanism for which the word government calls forth misleading connotations, for leaders did not “govern” in the sense that inheritors of the European tradition understand. Social and spiritual sanctions and the persuasion and example of leaders constrained and guided individual behavior. The autonomous bands looked to chiefs and headmen who counseled but did not command, and who spoke for their followers only as their followers consented. When bands came together, tribal councils made decisions and determined policy, not by majority vote but by consensus. Exalting the individual, rejecting authoritarianism, often fostering factionalism in both tribe and band, the political system made decisive or unified action difficult, especially in times of danger or crisis.

Though less combative than some other natives, the Nez Perces nonetheless knew how to make war. With lance, bow and arrow, warclub, and shield, they fought fiercely with their enemies on the south and sparred with the Plains groups to the east. Their weapons, techniques, and goals resembled those of the Plains Indians, from whom they had been largely borrowed. As with food gathering, spiritual life, and the political system, warfare accentuated the individual. Leadership depended on personal influence rather than command, warriors obeyed or disobeyed as personal inclination dictated, and combat usually took the form of an explosion of personal encounters rather than a collision of organized units. With the Blackfeet, Crows, Sioux, and Assiniboines east of the Rocky Mountains, the Nez Perces, often in alliance with the Flatheads, conducted the sporadic raid and counterraid characteristic of the Plains war complex. The principal aims were wealth in horses and other plunder and the war honors on which one's rise to prominence greatly depended. Against Shoshonis, Paiutes, and Bannocks to the south the hostility was chronic and deadly. The same aims prevailed, but fortified by genuine historic animosities rooted in overlapping hunting grounds. In these wars, which were both offensive and defensive, the Nez Perces also joined with friendly neighbors on the west—Umatillas, Walla Wallas, and Cayuses.

The Nez Perces differed in many ways from Apaches, Navajos, Pueblos, Cheyennes, and Mandans, as likewise these people differed from one another. In language, dress, shelter, food, means of transportation, spiritual beliefs, political and social organization, and other cultural traits, the groups displayed variations reflecting environmental and historical influences. Navajos lived in log-and-sod hogans and herded sheep. Apaches preferred to travel on foot. Pueblos lived in communal apartments of adobe and planted corn and beans.

Yet for all the differences there were significant similarities. Most groups, for example, even the agricultural Pueblos and Caddos, practiced a precarious subsistence economy and depended on a simple technology. Most worshiped deities residing in nature and strove for a life in balance with the natural world. Most exalted war and fought in ways that exalted the individual warrior. Most placed a premium on individual freedom and government by persuasion and consensus and withheld from their chiefs the power to command or enforce. All the natives, like the Nez Perces, venerated their homeland and looked on it with a keen sense of possession. It was a group possession, however, recognizing the right of all to partake of its bounty. No individual could “own” any part of it to the exclusion of others. Use privileges might be granted or sold, but sale of the land itself was a concept foreign to the Indian mind. The earth, Chief Joseph told treaty commissioners, was “too sacred to be valued by or sold for silver and gold.”7

Perhaps the most critical similarity in the struggle with the white people was a strong sense of group identity. Indians saw themselves as many different peoples rather than as a single Indian people with common interests and, especially to the point, a common danger from the whites. Indeed, a group's name for itself frequently meant “the people,” and its word for a neighboring group as often translated into “enemy.” Flatheads or Lipans looked on themselves above all as Flathead or Lipan, and only dimly if at all as Indian. In their minds...