![]()

1

The Society of Jesus and the First Aldeias of Brazil

Alida C. Metcalf

In 1549 the first Jesuits disembarked in the Bay of All Saints with the huge responsibility of converting the indigenous peoples of Brazil to Christianity. For João III, the king of Portugal, the spreading of Christianity was the stated justification for colonizing Brazil, and hence these six Jesuits had crossed the Atlantic Ocean with his first governor appointed to rule over Brazil, Tomé de Sousa (1549–1553). A Portuguese settlement, Vila Velha, already existed right inside the entrance to the bay, and it was here that the first Jesuits, the governor, and many others stepped ashore. All around the bay and up and down the coast lay traditional indigenous villages. While the Jesuits would begin their evangelism by visiting these villages, the governor turned his attention to building a new capital, to be known as Salvador (see map 1). Within a decade, unhappy with the slow pace of evangelism, the Jesuits created a new kind of village, a mission village, where they believed their enterprise would succeed. These new mission villages replaced the traditional villages; indeed, they became the defining institution of the Jesuit project in Brazil.

The Jesuits belonged to a new religious order—the Society of Jesus—where members did not live in monasteries but rather dedicated themselves to a life in the secular world. Early Jesuit brothers and priests in Europe were known for their preaching. Standing on street corners, in plazas, in the market, or walking to distant hamlets, the first Jesuits preached out in the open air and actively sought those in need. Their proximity to João III of Portugal had opened up to them the vast world beyond western Europe explored by Portuguese sea captains and merchants. With the king’s patronage, the Society of Jesus now sought to establish missions abroad in order to bring Christianity to those who had never been evangelized. The timing of their arrival in Brazil fit into this global missionary enterprise: Francis Xavier had opened a mission in India (1542) and the Spice Islands (1546–1547); the very same year that the first Jesuits arrived in Brazil (1549), a Jesuit priest took up residence in Ormuz at the entrance to the Persian Gulf, and Xavier landed on the Japanese island of Kyushu.1

The first Jesuits in Brazil chronicled their early missionary enterprise in dozens of letters, the majority written to members of the Society in Portugal.2 These letters are one of the most important sources for understanding sixteenth-century Brazil, and they are especially rich if examined for what they reveal about the Jesuits themselves. Historians have used these letters to assess how the Jesuit project changed when confronted with realities in the field.3 After thirty years in Brazil, Jesuits began to write the first histories of their efforts.4 Between the letters and these first histories, it is clear that the Jesuits saw the creation of the aldeia, or mission village, as one of their most important accomplishments. Historians have noted that the mission village was not imposed from Lisbon or Rome, but evolved on the ground in Brazil.5 How the Jesuit missionaries described their movement away from their preferred evangelism, which rested on periodic visits to traditional Indian villages, to create instead these permanent mission villages is the subject of this chapter.

EARLY VILLAGE ENCOUNTERS

The word aldeia in Portuguese is of Arabic origin and it simply means village. In Brazil, colonists and Jesuits sometimes used the term to describe autonomous Indian villages, but over time aldeia or aldeamento came to mean the mission villages created by the Jesuits. In this chapter, aldeia will be used to refer to the Jesuit mission villages.

Jesuits first came into contact primarily with Tupi- and Guaranispeaking groups living around the Bay of All Saints in the region known as Bahia; in the regions farther south known as Ilheus, Porto Seguro, Espírito Santo, and Rio de Janeiro (after the defeat of the French colony [1555–1560] in the Guanabara Bay); and in the southernmost colony of São Vicente (later São Paulo). Farther north, they encountered the Caeté in Sergipe and Pernambuco. All of these native peoples were already interacting with the Portuguese, and many had been enslaved by the colonists. Beyond the Tupi villages already in contact with the Portuguese lived the Guarani to the south and west of São Vicente, and Gê-, Carib-, and Arawak-speaking groups in central Brazil and Amazonia. Those areas still under the control of indigenous groups the colonists and the Jesuits called the sertão (wilderness or backlands).

The first Jesuits directed their initial evangelism campaign to those still living in traditional villages relatively near the Portuguese settlements. The Tupi villages consisted of large multifamily lodges or longhouses made of straw, known as ocas. Manuel da Nóbrega, leader of the Jesuit mission to Brazil, described the ocas as “very large” accommodating fifty married men with their wives and children, and he noted that they slept in hammocks next to fires that kept them warm at night. In 1550, João de Azpilcueta explained that the villages were not fixed in location, but moved often, sometimes unexpectedly. Since the longhouses were made of straw, fire was an ever-present danger and entire villages could be easily burned. Disagreements within the village could lead to the torching of a longhouse in anger, and once one house was in flames, the fire spread, quickly engulfing the entire village. “This happened now, during a recent night,” Azpilcueta wrote, adding that it “seemed like the Day of Judgment.” The villages moved frequently because of slash-and-burn agriculture. Once lands wore out, new plots were cut and burned out of the virgin forest, which often required the moving of the village. Luis da Grã saw the constant relocation of traditional villages as problematic for the Jesuits. The villages in São Vicente moved when the fields wore out, he wrote, while the houses themselves, whether made from earth or straw, lasted only three or four years. As a result the Jesuit mission lacked permanence and had to be constantly reinitiated when villages split or moved.6

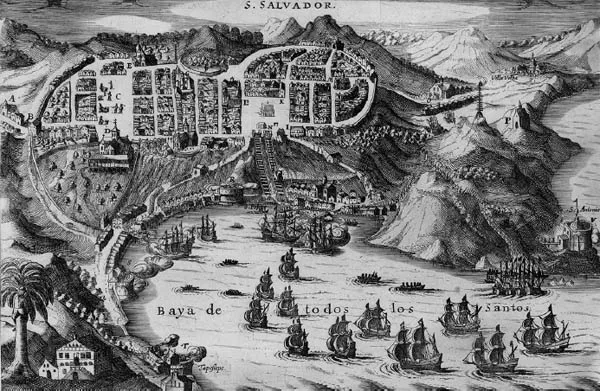

Figure 5. Indigenous villages could be found throughout the fertile lands surrounding Bahia’s Bay of All Saints. At the plaza labeled C, natives traded goods at one of Salvador’s urban markets. Indians responded to colonial intrusions in a variety of ways, including conversion to Christianity, violent and nonviolent resistance, and migration to other regions. Source: Reys-boeck van het rijcke Brasilien, Rio de la Plata ende Magallanes, daer in te sien is, de gheleghentheyt van hare landen ende steden . . . [Dordrecht?]: n.p., 1624. Courtesy of the John Carter Brown Library at Brown University.

These descriptions by Jesuits match other contemporary accounts of indigenous villages in Brazil in the middle of the sixteenth century. Jean de Léry, a French Calvinist who lived in the Guanabara Bay in 1557, described the longhouses as more than sixty paces long and a typical village as having from five hundred to six hundred people. The German mercenary Hans Staden, who lived in Brazil in the 1550s, described Tupinambá villages north of São Vicente. Each village had up to seven longhouses, which formed a sort of square surrounded by a wooden palisade. Each longhouse was 14 feet wide and up to 150 feet long. The vaulted roof was 12 feet above the ground; inside the chief of the hut had his space in the center, while couples with their children strung their hammocks along the sides. Woodcuts in published books or images painted on maps provide a visual idea of these villages; the woodcuts made under Staden’s direction include several representations of the palisaded villages with the longhouses. Jean Rotz, a mapmaker and sailor who had traveled to Brazil in the 1540s, painted a palisade village with four longhouses strung with hammocks forming a public square on his map of Brazil in 1542. Although represented as a single, seemingly permanent place in a woodcut or on a map, the traditional indigenous villages actually moved frequently. They were prone to fission when conflicts erupted, and therefore it was not uncommon for villages to split apart when groups broke away and established independent villages.7

Although we cannot know for certain the size of these villages, and indeed they most certainly varied in size, historian Warren Dean estimated the size of each longhouse in the Tupinambá region around the Guanabara Bay in 1551 as having 135 people living in each lodge. He further calculated the size of each village as having, on average, 607 persons. These estimates can serve as a rough indication of the size of the traditional Indian villages first visited by Jesuit missionaries. João de Azpilcueta described visiting a village with 150 “fires” or hearths in 1551, while another had 200. These would have been the fires kindled inside the ocas, next to which families strung their hammocks.8

According to the Jesuit historian Serafim Leite, there were six or seven traditional villages in Bahia where the early evangelization took place.9 Walking on foot, the Jesuits approached them and through their interpreters began their outreach to the native peoples through speech. Seeing themselves as the spiritual intermediaries between the Indians and God, the Jesuits talked, presented arguments, preached, taught through dialogues, and recited prayers.10 Of the original six, João de Azpilcueta acquired enough facility with the Tupi-Guarani language that was widely spoken along the coast of Brazil to model the missionary approach first envisioned by the Jesuits. Within a year, Azpilcueta had built a church near the villages he visited; there he said Mass and taught in the Indian language. He had succeeded in articulating in the Tupi-Guarani language key Christian beliefs, such as the Ten Commandments.11

Azpilcueta and other Jesuit missionaries developed persuasive arguments that they believed convinced many in the traditional villages to convert willingly to Christianity. Leonardo Nunes, who was entrusted with establishing the Jesuit mission farther south, in São Vicente, described in a letter that since the Indians “greatly fear death and the day of judgment and hell,” he ordered his interpreter “always to touch on this in the conversations, because the fear puts them in great confusion,” thus making conversions more likely. A theme stressed by Vicente Rodrigues in his conversations and preaching was that “the time of dreams had passed” and that it was time for Indians to “wake up and hear the word of God, our Lord.” Also in São Vicente, Pero Correia, a Portuguese colonist who joined the Society after it arrived in Brazil, promised Indians, “if they believed in God that not only would our Lord give them great things in heaven . . . but that in this world on their lands he would give them many things that were hidden.”12

In addition to these themes, Jesuit missionaries sought appealing ways to present Christianity, believing that music, styles of discourse, and children provided an important entrée into the villages. One Jesuit observed: “because they love musical things, we, by playing and singing among them, will win them.” A group of Portuguese children, who had come to Brazil as orphans to be raised by the Jesuits, became compelling models for conversion, so the Jesuits believed. When the children went from village to village in Bahia, one brother wrote, they adopted indigenous songs and instruments, “singing and playing in the way of the Indians and with their very same sounds and songs, changing the words in praise of God.” They shook rattles, beat sticks on the ground, and sang at night. This followed in the footsteps of Azpilcueta who, during the first year of the Jesuits in Brazil, had adapted the Pater Noster [Lord’s Prayer] to “their way of singing” so that the Indian boys would learn it faster and enjoy it more. “We preach to them in their way,” Ma...