![]()

Chapter 1

• • • THE INCOMPARABLE TORTILLA

Deep in the highlands of Chiapas in southeastern Mexico, a contemporary Zinacantecos shaman kneels before three wooden crosses decorated with pine tree tops and bunches of red geraniums. As he prays to his ancestral Maya gods who reside inside the volcanic mountains, the shaman plants white wax candles in the earth before the shrine, waves copal incense over the lighted candles, and pours a powerful brew of cane liquor on the ground. For the ceremonial smoke, he lights cigarettes in the guise of burning incense. And he presents corn tortillas, the life-giver, to eat, perceived in the image of the flaming candles as the heat energy of the sun released into the soil to grow the sacred corn. “The gods’ meals are like those eaten by men. Or, as the Zinacantecos express it, men eat what the gods eat,” explained anthropologist Evon Vogt. Fed and contented, the gods are ready to talk and the Zinacantecos listen to their ancestors, spiritual counselors who provide order to a world of crop failures, squabbling relatives, and modernization.

More than two thousand miles northwest of the mountain shrine, Joe Bravo, a Chicano artist, pays tribute to his Hispanic heritage in his backyard studio in Los Angeles, California. He paints on a twenty-seven-inch wheat flour tortilla, custom made by a local tortillería. The ritual begins with selecting the desired texture, shape, and color of the tortilla and cooking it over an open flame. Burn marks are a distinctive characteristic. With bold acrylics he paints an ethnic Elvis Presley with a dark Latino complexion, a snake entwined Medusa or Our Lady of Guadalupe, Patron Saint of Mexico. Bravo’s canvas is at the mercy of the elements, and after the paint dries he protects it against moisture and insects with an acrylic varnish. He grew up eating tortillas: “As the tortillas have given us life, I give it new life by using it as an art medium.”

La Virgin of Guadalupe. Tortilla Art by Joe Bravo. (Courtesy of Joe Bravo)

Our Story Begins in Mesoamerica

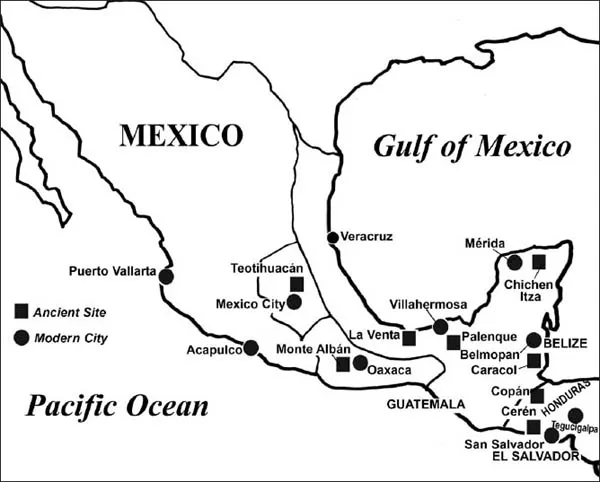

How did this seemingly humble food become such a venerated object of modern ritual and art? The rich cultural story of the tortilla begins its narrative in ancient Mesoamerica, a cultural and economic region extending from present day Central Mexico to Belize, Guatemala, El Salvador, Honduras, Nicaragua, and Costa Rica. The influence of this region also stretched into southeastern Central America, northwestern and northeastern Mexico, and what is now the southwestern United States. In the highlands—the Central Valley of Mexico, the mountainous region of Oaxaca, and the intermountain basins of Chiapas and Guatemala—the people terraced and irrigated the agricultural triad of corn, beans, and squash; mined gold, silver, and obsidian; and ruled from powerful urban metropolises. In the lowlands—the eastern coasts of the Gulf of Mexico and the Caribbean, and the western Pacific coast—the native people added chiles and tobacco to the triad, planted cacao trees, extracted salt from the earth, and built scattered rural centers of political authority. The geography was as varied as its ethnic populations and provided the basis for the tortilla’s culinary and cultural diversity.

Ambitious politicians and priests established the basic Mesoamerican pattern of the community. Rulers administrated, priests celebrated, warriors fought, long-haul merchants traded, and peasants labored to build temples and palaces and grow food.

In the southern lowlands of Veracruz, Mexico, and the neighboring state of Tabasco, from 1200–400 BC the hereditary elite class of the Olmec, acknowledged as the Mother Culture of Mexico, pronounced the rules of their land. They performed religious rituals in the shadow of ceremonial mounds and pyramids constructed out of clay and earth. They carved colossal heads out of volcanic basalt, some over nine feet high, of their mighty kings and gods. Since there were no draft horses, cattle, or wagons before the Spanish conquest, the workers hauled tons of basalt by hand from a distance of more than fifty miles to the capital San Lorenzo Tenochtitlán.

Mesoamerica map. (Tom Wilbur; redrawn from Map of Mesoamerica, Foundation for the Advancement of Mesoamerican Studies)

In the highlands of the Valley of Oaxaca, Mexico, Mesoamerican glyphs appeared in a pictorial form of signs and a common number system. As early as 500 BC, Zapotec priests described their ceremonies in incipient forms of writing on the stone edifices of temples built 1,300 feet above the plain in the capital of Monte Albán. Below, the lowly laboring subjects in the fields looked up at the stone and mortar of the ruling class.

In the lowlands of Petén, Guatemala, at the capital of El Mirador in the height of its power between 300–150 BC, the Maya reached to the sky to praise their deities. Faced with cut stone and decorated with stucco masks of the gods and goddesses, the Danta Pyramid soared 270 feet high, as tall as an eighteen-story building. Its companion pyramid, Tigre, topped at 180 feet.

Major city-states emerged. In the Valley of Mexico over one hundred thousand people resided in the city of Teotihuacán, which spread over eight perfectly surveyed square miles with wide streets laid out on a grid plan, central markets, and three grand pyramids, the Pyramid of the Sun, the Pyramid of the Moon, and at the southern end of the Avenue of the Dead, the Temple of Quetzalcóatl. Over time, between AD 200–700, Teotihuacán became one of the largest cities in the world. Yet by AD 900 most of the great Classic city-states were abandoned, leaving unanswered questions to explain their collapse.

The people of Mesoamerica did regroup. After AD 950 regional commercial governments emphasized grand houses and royal feasts, art and science, and military and economic alliances. In the Mexican Yucatán, the elite class of Maya astronomers surveyed the sun, moon, and planets from the platforms and windows of the ornate stone carved Caracol observatory at the urban center of Chichen Itza. In Central Mexico in 1325, the Mexica, the most dominant of the seven Aztec tribes, founded the lake island city of Tenochtitlán, the site of present day Mexico City. In the center of their capital city they framed the political and religious complex of more than seventy-five formal structures around the Templo Mayor, the Great Temple, dedicated to two gods, Huitzilopochtli (God of War) and Tlaloc (God of Rain and Agriculture). The Aztec grew to form one of the most influential empires in Mesoamerican history until the arrival of the Spanish conquistadores in the sixteenth century.

Over three major time periods—the Preclassic, or Formative, from 1500 BC–AD 300, the Classic from AD 300–950, and the Postclassic from AD 950–1521—the complex histories of these civilizations are each rooted in the history of corn, a grain discovered, domesticated, and ritualized by the people throughout Mesoamerica.

Sin Maíz No Hay País

For the Mesoamericans, there was no country without corn, “Sin maíz no hay país.” For the Maya, the Aztec, the Zapotec, and the wide diversity of regional cultures from the nomadic people of the north to the southern periphery to the western frontier, corn was the equivalent of the staple European bread. In fact, in Old World Europe corn was the generic term for a variety of grains, such as wheat and rice and barley. Maize was a New World name, believed to be a variant of the word mahiz spoken by the indigenous Taíno people to an awed Christopher Columbus, who pulled back the leaves of the corn plant to reveal small white kernels.

But the Mesoamericans were not content with one name for this extraordinary grain that transformed the nomadic hunter and gatherer into the sedentary farmer and homemaker. In the Valley of Mexico the people called corn by its Nahuatl name tlaolli and changed labels to distinguish each stage of the corn plant’s development. The tender and undeveloped ear was xilot; as it formed kernels, elotl; and the dried ear, centli.

Corn, related to wild primitive teosinte grass, was cultivated between 7500–5000 BC in Mexico and Central America. In the Guilá Naquitz cave near Mitla in the Valley of Mexico, archaeologists uncovered cob fragments dating to approximately 4300 BC. Initially the early foragers collected the primitive corn from the wild, but gradually they deliberately took a few of the largest and most flavorful seeds and planted them beside their dwellings, and now they produced a corn crop. But corn is wind pollinated, carried by the wind from the tassels (male) to the silks (female). Thus, distance, wind currents, and cross-contamination affected the pollination of corn, leading to a large number of corn varieties over thousands of years of selection.

Wherever they settled, whatever the climate or soil, the diverse people of Mesoamerica planted many varieties of corn and it grew. From season to season, the farmers saved seeds from the largest, most productive and hardy plants. With repeated selection, corn varieties developed for every need and every microclimate: the humid lowlands, the temperate mountain valleys, and the short rainfall seasons of the desert. One variety dyed maize beer a reddish color; the broad husks of another variety were used to wrap tamales. Starchy mature corn was preferred for tortillas.

The Mesoamericans prayed to gods and goddesses of rain and corn, talked to the tender shoots of corn, touched the moisture of the soil, and harvested the ears to nourish their bodies and souls. And some believed the first human beings were created from corn dough.

Corn Dough Beginnings

Consulting the Popol Vuh, the sacred Book of Counsel, the lords of the Quiché Maya of the Guatemalan highlands told the story of the first sunrise, the glories of the gods, and the rise of the maize deity, father of the mythical hero twins Hunahpú and Xbalanqué who crushed monsters and fought evil to make the world a decent place for humans. The human being was the next challenge for the gods.

After much deliberation, the forefather gods, Tepew and Q’ukumatz, formed figures from mud and wood, semblances of people but unable to walk or talk and, most important, pay homage to the gods. Stumped, the gods turned to Grandmother Xmucane at the high mountain named Split Place, Bitter Water Place. She picked up a jug and walked to the mountain stream where she mixed the clear water with kernels scraped from corn grown inside the sacred mountain. Then she knelt before the grinding stone to massage the corn into a coarse dough. Now the gods had the life force of corn to work with and they molded the dough into four men and four women made of flesh, perfect in their own image. And the gods were alarmed, for only gods were divine. So they blew a few puffs of fog in the eyes of the humans to remove the divine visionary power, leaving behind the wise guidance of the Popol Vuh.

Beyond the borders of the Maya, the Aztec spun their own legend of creation. The great cities of the Maya were in decline when the Aztec tribes immigrated to the Valley of Mexico.

Led by the deity Huitzilopochtli, they wandered south from the harsh desert of northern Mexico, a place they called the mythical Aztlán (Place of the White Heron). Along the arduous journey, they told and retold versions of their creation stories, where they came from and who they were as they made their way into an unknown world.

The Aztec paid homage to two primordial deities, Ometecuhtli, Lord of Duality, and Omecíhuatl, Lady of Duality, who delegated the monumental task of creating the world to their sons, Quetzalcóatl and Huitzilopochtli. These obedient sons made fire, sun, rain, rivers, mountains, plants, animals—a complete universe ruled by the gods. It only remained for the gods to create human beings.

Hero-god Quetzalcóatl, the feathered serpent, descended to the underworld of Mictlán to gather the bones and ashes of previous lost generations, intending to recreate humans from the bones of the spirits. The more bones he accumulated, the more he dropped and broke, and that is why, the Aztec legends said, some people are short, others tall. Undeterred by his less than perfect collection, Quetzalcóatl delivered his jumble to the earth fertility goddess Cihuacóatl-Quilaztli, the lady of the serpent skirt and necklace of human hearts. Cihuacóatl ground the sacred corn with the ancestral bones to make a dough, added a bit of sacrificial blood from Quetzalcóatl to fuel the creation, and after four days, created a male child followed in another four days by a female child.

Masa

The corn of the myths was good food, an important source of carbohydrates and protein. Early Mesoamericans chewed the entire ears—cob, husk, silk—of young tender corn, or roasted and boiled on the cob at its peak flavor. To grind corn into dough, the women crushed partially cooked and softened corn kernels between the mano, a hand stone that resembled a small elongated rolling-pin, and the metate, a slightly hollowed grinding stone carved from volcanic rock. The Aztec woman molded the ball of grainy dough in her hands and called it textli; the Maya called the dough yokem. The Spanish renamed it masa.

It was the woman’s task to spend four or five hours ...