This is a test

- 200 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Bad Clowns

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

Bad clowns—those malicious misfits of the midway who terrorize, haunt, and threaten us—have long been a cultural icon. This book describes the history of bad clowns, why clowns go bad, and why many people fear them. Going beyond familiar clowns such as the Joker, Krusty, John Wayne Gacy, and Stephen King's Pennywise, it also features bizarre, lesser-known stories of weird clown antics including Bozo obscenity, Ronald McDonald haters, killer clowns, phantom-clown abductors, evil-clown panics, sex clowns, carnival clowns, troll clowns, and much more. Bad Clowns blends humor, investigation, and scholarship to reveal what is behind the clown's dark smile.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Bad Clowns by Benjamin Radford in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Folklore & Mythology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER 1

A Short History of the Earliest Clowns

Clowns have been around in one form or another for millennia; they constitute an ancient archetype encompassing countless variations. In her classic study The Fool: His Social and Literary History, Enid Welsford traces the clown (more specifically, the European clown) to

ancient Greece, where we discover him [in various forms]; now as a squat slave with padded stomach, pelting the spectators with nuts or parodying the wanton orgies of Dionysus, now as a bald-headed, ass-eared, hook-nosed fellow bearing a striking resemblance to the half-witted jesters of a later period. This bald-headed clown or sannio was a long-lived gentleman, for we find him still flourishing in the early years of the Roman Empire as “secondary mime” or “stupidus” whose business it was to repeat the words and make unsuccessful attempts to imitate the actions of others, and to be deceived by everybody. He wore a long pointed hat, a multicoloured patchwork dress, and according to St. Chrysostom it was part of his duty to “be slapped at the public expense.” (Welsford 1966, 278)

This theme of slapping clowns for amusement and pleasure would carry over into later plays and films such as He Who Gets Slapped.

Clown historian Beryl Hugill notes that “the actual word ‘clown’ did not enter the language until the sixteenth century. It is of Low German origin and means a countryman or peasant. Its original meaning is allied in sense to the word for a Dutch or German farmer, ‘boor,’ from which we get the adjective ‘boorish’. So ‘clown’ meant someone who was doltish or ill-bred” (Hugill 1980, 14). The everyman nature of the clown was established early, and the figure came and went over the centuries but flourished during the Renaissance in the commedia dell’arte, a theater genre popular in Italy in the sixteenth century.

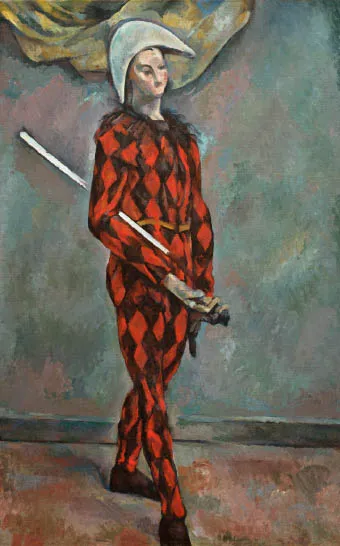

The characters of the commedia dell’arte were caricatures of familiar types representing young and old, urban and rural, sophisticated and rustic, rich and poor, and native and foreigner. These types were divided into high and low characters. The former included lovers who were young and attractive and whose speech was the cultivated, courtly dialect of Tuscany. Low characters included clowns (zanni) and their female counterparts, the maids. . . . Harlequin, Brighella, Pierrot (Pedrolino), and Pulcinella are all low, masked clowns. . . . Harlequin and Brighella . . . were both from Bergamo, a town considered by Venetians to be both rustic and crude. Harlequin was the more crude of the two—always hungry, always nosy, always getting into trouble, and always vexing his master. His costume was made up of multicolored patches and a wooden sword or bat hung at his side (the original slapstick). He wore a black half-mask with bushy eyebrows and mustache, carbuncles, and a snub nose, above which he wore a felt hat with a rabbit’s tail. (Royce 1998, 135–36)

The crude, chaotic Harlequin character (typically wearing a mask and a colorful, diamond-patterned costume) is clearly a clown, but his roots run sinister, as there is a link between him and the diabolical world: “Harlequin appears first in history or legend as an aerial spectre or demon, leading the ghostly nocturnal cortege known as the Wild Hunt. [Eventually] the Hunt lost some of its terrors and the wailing procession of lost souls turned into a troupe of comic demons who flew merrily through the air to the sound of song and tinkling bells” (Welsford 1966, 292). Indeed, the Harlequin character often appeared in plays and stories as involved with magical creatures including fairies (which, despite the sanitized and Disneyfied depictions most modern children are familiar with, can be evil, cruel creatures; for an excellent discussion of fairy sadism and “intrafairy violence and warfare,” see Silver 1999).

FIGURE 1.1. Harlequin (1888–1890), by Paul Cezanne. National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC. Photograph by Alexander R. Pruss, used by permission of a Creative Commons license, Wikimedia Commons.

In the next century the Roman du Fauvel shows a further comic and dramatic development of the “maisinie Harlequin,” which now appears not as a band of aerial sprites, but as a noisy troupe of mummers, rioting outside the bridal chamber of a newly married couple whom they desire to mock. The diabolical aspect of Harlequin was not, however, wholly forgotten. . . . It was mainly through the religious drama that Harlequin developed from an aerial demon into a comic devil, and so was prepared for his final migration to the Italian comic stage. For Harlequin has a mixed ancestry, and is himself an odd hybrid creature, in part a devil created by popular fancy, in part a wandering mountebank from Italy. (Welsford 1966, 292–93)

Though the echoes of this diabolical, itinerant trickster can be seen in modern clowns, written accounts of his exploits are at least four centuries old:

Harlequin the Clown makes his first appearance in literature in two curious poems published in Paris in 1585 . . . where he is represented as a kind of diabolical acrobat. . . . One poem . . . relates how one night Harlequin had a vision of Mother Cardine, a villainous old woman who in her lifetime kept a brothel in Paris, and had now risen from the underworld in order to beg “her son” to deliver her from the torments of Hell. As soon as he awoke from the dream Harlequin journeyed to the river of death, leapt onto Charon’s shoulders as lightly as a monkey, and proceeded to divert that grim ferryman by putting out his tongue, rolling his eyes and performing a thousand antics. Having made a further conquest of [three-headed dog] Cerberus, he went on to divert even the King of the Underworld by his acrobatic feats.

Harlequin’s comic persuasion worked, and in return he was promised anything he desired—whereupon he promptly requested that Mother Cardine be restored to life, and his mission was accomplished (Welsford 1966, 294). The clown-defeats-Death theme would reappear a century later in the Punch and Judy show (see next chapter).

Harlequin, for much of his existence, was silent. Like most clowns he performed in pantomime. This silence is one aspect that makes a clown mysterious and unnerving, for his thoughts and motivations—whether benevolent or malicious—may be on his mind but are not on his tongue. (The quiet-killer theme is also exploited in modern horror and slasher films, with silent masked murderers such as Michael Myers and Jason Voorhees relentlessly stalking their helpless prey.) Some later incarnations of the Harlequin employed speech, but today most clowns (such as those in circuses) don’t speak—not as a scare tactic but simply as a practical matter. A traveling circus may visit dozens of countries, and a clown can perform anywhere since their silent slapstick and pratfalls are universal and need no translation. Some clowns, such as North American ones who perform at birthday parties, of course, often speak and tell jokes.

It’s interesting to note that historically the clown figure is generally devoid of allegiance; he has no masters and is a man in full and at his own command. Enid Welsford discusses a character in the play Life Is a Dream, in which a clown, Clarin, is caught in a war between powerful foes. He says,

To me it matters not a pin,

Which doth lose or which doth win,

If I can keep out of the way!—

So aside here I will go,

Acting like a prudent hero,

Even as the Emperor Nero

Took things coolly long ago.

Or if care I cannot shun,

Let it ’bout mine ownself be;

Yes, here hidden I can see

All the fighting and the fun

(Quoted in Welsford 1966, 280).

Clarin is a capricious clown looking after his own self-interest and perfectly happy to toady up to whoever wins the battle.

Certainly some clowns were employed by circuses or were jesters kept at the pleasure of a royal court, and to that extent they had some allegiance to those who fed and housed them. But even then they would often mock those they served; a jester might gently (and safely) rib a king about his weight or wealth, for example, while a circus clown might make a joke about how expensive the cotton candy sold at the concession stand is. “The court jester was a fool licensed to speak his mind only in the disguise of nonsense,” notes Hugill. “This tolerance stemmed from the belief that idiots were divine and that their presence formed a magic protection from evil. Consequently, royal households generally included an imbecile, for entertainment as well as protection” (Hugill 1980, 14). This theme of the clown role serving as a protected pretext for expressing truth or unpopular opinion would become an important part of later clowns.

The commedia dell’arte was popular for centuries and can still be found today; its spawn Harlequin, however, is more of a relic. As times changed the clown shed old clothes for a newer form. In his examination “Clowns on the Verge of a Nervous Breakdown,” Andrew McConnell Stott notes that “at the end of the nineteenth century, a new figure emerged from the ashes of the harlequinade—a clown intent not on laughter but on awful, bloody revenge. He made his first appearance in Ruggerio Leoncavallo’s opera I Pagliacci (1892). . . . Having discovered that his wife Nedda is conducting an affair, Canio, dressed for his role as a clown, confronts her and her lover and murders them both” (Stott 2012, 3).

Stott gives several examples in the decades after I Pagliacci, including “the anti-hero of Leonid Andreyev’s absurdist play He Who Gets Slapped (1914), a cuckolded and plagiarized writer who becomes a circus clown to indulge his feelings of humiliation, before falling in love with, and ultimately murdering, a beautiful bareback rider; the clown who commits suicide in front of a laughing audience in Fritz Lang’s Spies (1928); and the clown in the Lon Chaney movie Laugh, Clown, Laugh (1928), who, while undergoing treatment for a depression brought on by unrequited love, kills himself in the throes of an hallucination by zipping down a high wire on his head” (Stott 2012, 4). These and other films are discussed in a later chapter, and there are other threads we could follow, other early versions and variations of clowns. We briefly reviewed elements of the darker side of clown history, though there is another important historical bad clown, one so notorious and influential that he merits his own chapter. His name is Mr. Punch.

CHAPTER 2

The Despicable Rogue Mr. Punch

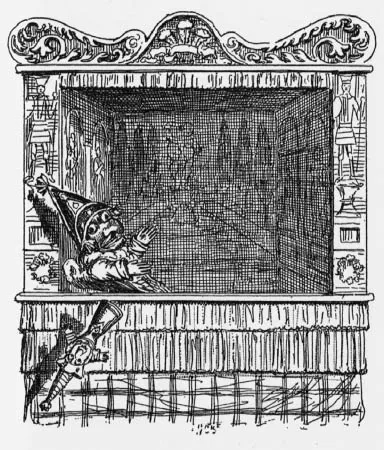

No discussion of bad clowns would be complete without a certain red-capped, hook-nosed, gleeful, wife-abusing serial killer named Mr. Punch. Punch is a thoroughly despicable and remorseless thug, and indeed therein lies much of his appeal to generations of children and adults. As horror novelist Clive Barker noted, “Fools obsess me, and always have, clowns too. Punch has always fascinated me because he’s so cruel and so funny at the same time” (Barker 1997, 88). He is the star in the classic Punch and Judy shows, the English version of which dates back to a performance in London’s Covent Garden on May 9, 1662, marking over three and a half centuries of this peculiar play.

“And what a play it is!” exclaimed pioneering American puppeteer Tony Sarg in his 1929 foreword to Punch and Judy: A Short History with the Original Dialogue.

What an unexampled category of crime! Mr. Punch himself, that braggart, blusterer, wife-beater, strutting Don Juan, with a half-dozen murders to his credit, what a very prince of villains he is! Truly, children were fed upon strong meat in the days that were. In these anemic times, the career of this arch-scoundrel of the puppet-stage strikes a full and robust note. Those were the days when rogues were rogues; and when children, untroubled by educational theories or parental scruples, were permitted to rejoice naturally in the cracking of heads, the din of battle, the triumph of Unworthiness over Virtue and the Law. (quoted in Collier 1929, 1)

FIGURE 2.1. Portrait of Mr. Punch, based on George Cruikshank’s illustration in Punch and Judy: A Short History with the Original Dialogue (1828).

Marina Warner, in her book Monsters of Our Own Making: The Peculiar Pleasures of Fear, touches on a key ingredient of Mr. Punch’s appeal in the play:

One of the most profound and puzzling features of the bogeyman is his seductive power: he can charm at the same time as he repels. . . . In the course of the play, Punch gleefully lays about him in a series of violent assaults. His victims include his own baby—whose torments raise the shrillest squealing from the audience. Mr. Punch is left to baby-sit by [his wife] Judy (also the butt of his big stick), and when he fails to put the baby to sleep, he batters it. Punch and Judy is considered good family fun. . . . His abuse is the play’s only running gag, now and then punctuated by the puppeteer’s up-to-date jokes inspired by the week’s news and television. Children find it very funny.

After the death of his “babby,” the ugly, obstinate, brutal gnome overcomes all obstacles—the policeman, a crocodile, a thief—which culminate in Mr. Death himself, whom Punch tempts to place his head in his own noose. (Warner 2007, 167)

FIGURE 2.2. Mr. Punch throws his crying “baby” out the window and into the audience. Illustration by George Cruikshank in Punch and Judy: A Short History with the Original Dialogue (1828).

The running commentary and jokes provided by the professor—the traditional name for a Punch and Judy puppeteer—are an important fram...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half title

- Title

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction

- 1. A Short History of the Earliest Clowns

- 2. The Despicable Rogue Mr. Punch

- 3. The Unnatural Nature of the Evil Clown

- 4. Coulrophobia: Fear of Clowns

- 5. Bad Clowns of the Ink

- 6. Bad Clowns of the Screen

- 7. Bad Clowns of the Song

- 8. The Carnal Carnival: Buffoon Boffing and Clown Sex

- 9. Creepy, Criminal, and Killer Clowns

- 10. Activist Clowns

- 11. Crazed Caged Carny Clowns

- 12. The Phantom Clowns

- 13. Trolls and the Future of Bad Clowns

- Notes

- References Cited

- Index