![]()

CHAPTER 1

A Brief Overview of the Aztec Empire

IMAGES OF BATTLES between brightly garbed Aztec soldiers armed with wooden swords edged with razor-sharp obsidian blades and ornately feathered shields and brightly shining steel-armored Spaniards with Toledo swords and charging horses are not alone in dominating the popular imagination. Scenes of temples atop high pyramids drenched by the blood of still-beating hearts torn from the chests of captives to briefly slake the insatiable appetites of savage gods are also vivid reminders of the Aztec empire. Wood smoke rose in unbroken ascent from the houses, mixed with the sweet aroma of burning resin from the temples. And the city awakened to the blowing of the conch shell and the beat of the temple drums.

Most of what is known about the Aztecs of central Mexico comes from Spanish accounts, as virtually all of the Native books were burned by the Spaniards. And their authors were primarily the conquistadors and the subsequent Spanish immigrants, as well as Christian priests, who wrote about the Conquest from a European perspective, leaving a rather distorted view of Aztec culture and society that emphasized the martial and the religious. The conquistadors hoped to secure royal patronage, and they therefore emphasized the rigors of the Conquest and the enormous obstacles they faced and overcame, while the priests wrote largely to aid in the Natives’ conversion from indigenous religions to Christianity. Both accordingly distorted the record in furtherance of their own ends.

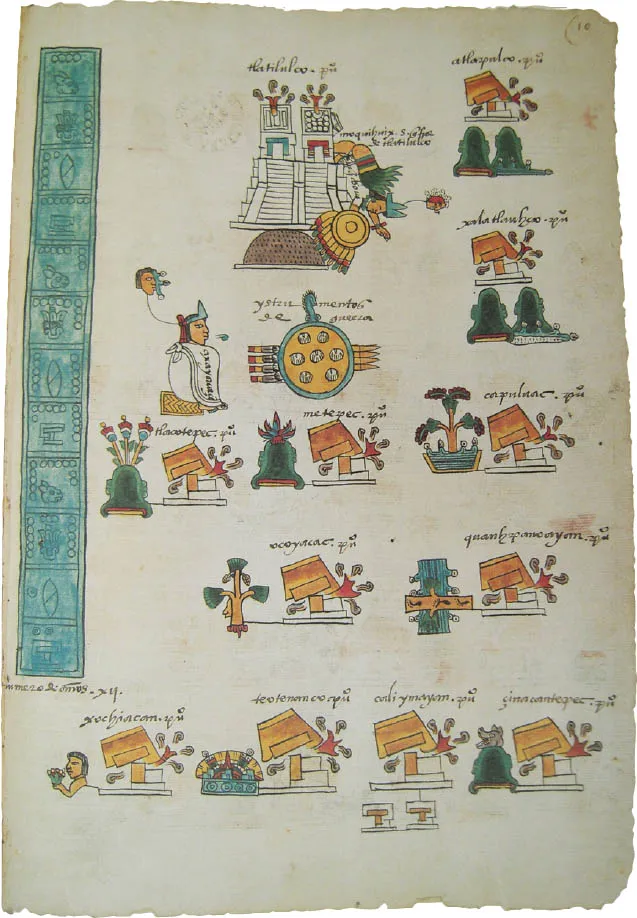

The Native books, or codices, were typically screen-fold manuscripts written on Ficus bark paper or deerskin and covered with a thin lime coating to provide a white base on which the content was painted. Very few pre-Columbian codices survive from central Mexico, perhaps up to five, but probably only one, the Codex Borgia, which records monthly ritual festivals. Fortunately, a number of Native accounts were written in the pre-Columbian style during the early colonial period, reflecting earlier ones that had been destroyed. Among these are tribute records, accounts of religious festivals, migration legends, and Native histories in an annal style that eschews narrative or cause and simply lists each year and its most notable events (fig. 1). Typically, these included the various towns conquered, the deaths of kings, and the accessions of their successors. But some also recorded such occurrences as comets, epidemics, earthquakes, and famines.

FIGURE 1. An annal page showing a portion of the reign of King Axayacatl and twelve of his conquests during the years 4 Rabbit through 2 House. (Courtesy of the Bodleian Library, University of Oxford, Codex Mendoza, MS. Arch. Seldon A.1, folio 10r.)

After the Conquest, some histories and other accounts were written in Nahuatl, the Aztec language, as well as a smattering of other indigenous languages, using the newly introduced Latin alphabet, but most were in Spanish, with a scattered few in other European languages. And it is largely on these accounts and archival documents that our understanding of the Aztecs is based, aided by relatively few, though important, archaeological discoveries. Most of Tenochtitlan’s ruins remain undisturbed beneath the sprawl of modern-day Mexico City, much of it under colonial buildings that are also of historical importance and thus protected.

A single, universally agreed upon overview of Aztec culture and history is not feasible in all its particulars, given the many differing historical sources, archaeological evidence, and competing theoretical perspectives by which it is viewed. But a generalized one is possible, despite disparities between the surviving historical sources. Some offer different dates for the same event, others differ in who the major actors were, and still others offer wholly different interpretations or causes of entire episodes. Sometimes, as in Spanish friar Bernardino de Sahagún’s king list, someone is omitted—in that case, the first king—and other times, someone is emphasized in some sources but ignored in most others, as is the case with the major fifteenth-century political functionary Tlacaelel in the Crónica X sources.1 And occasionally, historical sources displace an event or sequence of events in time, as the Crónica X sources do for the mid-fifteenth century.2 These differences have been explained as mere scribal lapses, intentional or otherwise, or as reflecting the varying perspectives of the cities where they were composed. And occasionally, they are all presumed to reflect some mythical perspective about which some inconsistency is to be expected, rather than actual historical events. Whatever the reasons, these differences pose daunting problems for the reconstruction of the Aztec past.

Though a major empire, the Aztecs were merely the last of a series of such polities in central Mexico, large and small, and the fact that today we are so aware of the Aztecs is essentially an accident of timing. Had the Spaniards arrived a hundred years earlier, they would have encountered the smaller Tepanec empire in the Valley of Mexico and barely noted the relatively unsophisticated Aztecs, who were, at that time, associated with the city of Colhuacan. Yet a century later, it was this seemingly insignificant group that they encountered and fought, while the memory of the Tepanec empire was rapidly fading into history.

Nevertheless, the Aztecs dominated Mexico when the Spaniards arrived and were thus the subjects of numerous Conquest-era and colonial chronicles. Indeed, despite their relatively recent rise and untimely fall, the Aztecs came to overshadow all Mesoamerican prehistory as the many accounts depicting their culture were and are used, not always wisely, to explain the other complex historically and archaeologically known groups.3

But when they were conquered, the Aztecs had been in power less than a hundred years, and in such a complex imperial society, kinship had generally been presumed to be secondary to class considerations. This was especially true of the Aztecs, where the various classes were clearly demarcated by the Aztecs themselves, conceptually and behaviorally, by differences in rights and attire, and the routes between the two were well defined, though limited.

What is known of the early history of the Aztecs before they settled their capital of Tenochtitlan is a blend of legend, myth, and perhaps reality. Because it is not reliably historical, there is little point in synthesizing the various surviving traditions to produce a distilled standard version based on majority rule. Nevertheless, one of the most complete accounts of the Aztecs’ migration is presented pictorially in the Codex Boturini and textually in the Codex Aubin.4 In those versions, the Aztecs departed from their original island homeland of Aztlan in the year 1 Tecpatl (AD 1146) before entering and then reemerging from Chicomoztoc (Seven-caves place), the legendary origin place of the other major peoples of postclassic central Mexico. There, they also acquired their patron god, Huitzilopochtli, whom they thereafter carried on their migrations until they entered the Valley of Mexico toward the end of the twelfth century, before they eventually settled permanently in Tenochtitlan in 2 Calli (AD 1325).

Until they reached the southern Valley of Mexico, where they interacted with more sophisticated urban peoples, and perhaps even until they established Tenochtitlan, the history of the Aztecs is sparse, focused primarily on recording the years of wandering interspersed by years of settlement in a manner they could not have known at the time, and is somewhat speculative. Furthermore, after they became an empire Aztec history was apparently altered to conform to their views of themselves and their historical past.

The Aztecs adapted to many Mesoamerican customs and practices during their southward migrations, but when they settled in Tenochtitlan, they were still a minor group of relative barbarians amid the sophisticated urban cultures of central Mexico. Yet by 1372, with growing prosperity and sophistication borrowed from their neighbors, they became a kingdom, embarking on 150 years of royal rule, 56 as a kingdom followed by 93 as an empire. When the Aztecs became an empire in 1428 after the overthrow of their erstwhile masters, the Tepanecs, Aztec society underwent a number of major changes, especially among the nobility. As with state societies generally, class now arguably determined one’s place in society more than kinship.5

With the Aztec rise, Tenochtitlan emerged as the dominant city of central Mexico, and by the time of the Conquest, its population had vastly outstripped that of any other city, not only in the Valley of Mexico but elsewhere in the New World and in Europe. Its burgeoning population changed the valley socially, politically, and economically, reorienting the primary flow of tribute from the former Tepanec capital of Azcapotzalco to Tenochtitlan. As their population and political control grew, the Aztecs converted more lakeshore to agricultural use and created new fields (chinampas) in the lake itself. These measures alone were inadequate to sustain the growing capital, and as tribute flowed into Tenochtitlan, the surrounding cities shifted away from manufacturing goods that could no longer compete with tribute-subsidized wares and turned increasingly toward more intensive agriculture, the products of which were increasingly in demand. Thus, the Aztecs at least partially integrated the Valley of Mexico into a single economic entity: Tenochtitlan became the primarily source of manufactured wares for the surrounding cities, and these cities, in turn, became suppliers of the agricultural goods increasingly needed to feed the burgeoning population of the capital.6

Among the most consistently chronicled events in Aztec histories was the succession of kings and their individual contributions to expanding the empire. Often these reigns were recorded using the years of accession through their subsequent deaths, creating a royal duration within which events were attributed, much as they were in medieval and early modern Europe.

The Aztec pattern of rule and succession was not universal in ancient Mexico. Who ruled and who succeeded to the various thrones differed by city, with no single uniform system prevailing, even among the tributaries in the Aztec empire. Part of the explanation for these differences is cultural and part simply the result of different degrees of political complexity, from city-states to city-state confederacies to empires.

During the early years of Aztec history when Tenochtitlan was a tributary to other cities in the Valley of Mexico, its kings were relatively weak and followed in direct succession, although not of a specified son. Thus, succession went from the first king, Acamapichtli, to his son Huitzilihuitl, who was in turn succeeded by his son Chimalpopoca. Chimalpopoca was killed, and he was arguably succeeded for sixty days by his son Xihuitl-Temoc. After Chimalpopoca’s death, direct royal father-to-son succession was abandoned. Chimalpopoca was instead succeeded by his great-uncle Itzcoatl, who overthrew the Tepanecs with the aid of other cities, notably Tetzcoco and Tlacopan, and set the Aztecs on the course toward empire. Itzcoatl was then succeeded by his nephew Moteuczoma Ilhuicamina, who was in turn succeeded by Axayacatl, who was either his son or his grandson. The surviving data conflict on this point, leaving resolution a matter of interpretation. Axayacatl was then succeeded by his brother T...