eBook - ePub

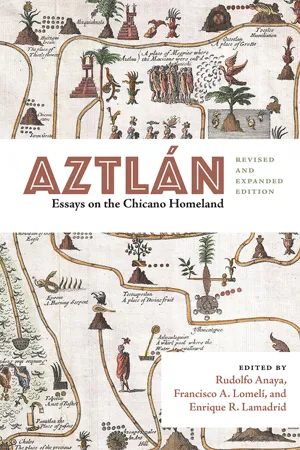

Aztlán

Essays on the Chicano Homeland. Revised and Expanded Edition.

Rudolfo Anaya,Francisco A. Lomelí,Enrique R. Lamadrid

This is a test

Share book

- 440 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Aztlán

Essays on the Chicano Homeland. Revised and Expanded Edition.

Rudolfo Anaya,Francisco A. Lomelí,Enrique R. Lamadrid

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

During the Chicano Movement in the 1960s and 1970s, the idea of Aztlán, homeland of the ancient Aztecs, served as a unifying force in an emerging cultural renaissance. Does the term remain useful? This expanded new edition of the classic 1989 collection of essays about Aztlán weighs its value. To encompass new developments in the discourse the editors have added six new essays.

Frequently asked questions

How do I cancel my subscription?

Can/how do I download books?

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

What is the difference between the pricing plans?

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

What is Perlego?

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Do you support text-to-speech?

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Is Aztlán an online PDF/ePUB?

Yes, you can access Aztlán by Rudolfo Anaya,Francisco A. Lomelí,Enrique R. Lamadrid in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Ciencias sociales & Estudios hispanoamericanos. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Topic

Ciencias socialesSubtopic

Estudios hispanoamericanosPart 1

AZTLÁN AS MYTH AND HISTORICAL CONSCIENCE

CHAPTER 1

EL PLAN ESPIRITUAL DE AZTLÁN

IN THE SPIRIT of a new people that is conscious not only of its proud historical heritage but also of the brutal “gringo” invasion of our territories, we, the Chicano inhabitants and civilizers of the northern land of Aztlán from whence came our forefathers, reclaiming the land of their birth and consecrating the determination of our people of the sun, declare that the call of our blood is our power, our responsibility, and our inevitable destiny.

We are free and sovereign to determine those tasks which are justly called for by our house, our land, the sweat of our brows, and by our hearts. Aztlán belongs to those who plant the seeds, water the fields, and gather the crops and not to the foreign Europeans. We do not recognize capricious frontiers on the bronze continents.

Brotherhood unites us, and love for our brothers makes us a people whose time has come and who struggles against the foreigner “gabacho” who exploits our riches and destroys our culture. With our heart in our hands and our hands in the soil, we declare the independence of our mestizo nation. We are a bronze people with a bronze culture. Before the world, before all of North America, before all our brothers in the bronze continent, we are a nation, we are a union of free pueblos, we are Aztlán.

Program

El Plan Espiritual de Aztlán sets the theme that the Chicanos (La Raza de Bronze) must use their nationalism as the key or common denominator for mass mobilization and organization. Once we are committed to the idea and philosophy of El Plan de Aztlán, we can only conclude that social, economic, cultural, and political independence is the only road to total liberation from oppression, exploitation, and racism. Our struggle then must be for the control of our barrios, campos, pueblos, lands, our economy, our culture, and our political life. El Plan commits all levels of Chicano society—the barrio, the campo, the ranchero, the writer, the teacher, the worker, the professional—to La Causa.

Nationalism

Nationalism as the key to organization transcends all religious, political, class, and economic factions or boundaries. Nationalism is the common denominator that all members of La Raza can agree upon.

Organizational Goals

1.UNITY in the thinking of our people concerning the barrios, the pueblo, the campo, the land, the poor, the middle class, the professional—all committed to the liberation of La Raza.

2.ECONOMY: economic control of our lives and our communities can only come about by driving the exploiter out of our communities, our pueblos, and our lands and by controlling and developing our own talents, sweat, and resources. Cultural background and values which ignore materialism and embrace humanism will contribute to the act of cooperative buying and the distribution of resources and production to sustain an economic base for healthy growth and development. Lands rightfully ours will be fought for and defended. Land and realty ownership will be acquired by the community for the people’s welfare. Economic ties of responsibility must be secured by nationalism and the Chicano defense units.

3.EDUCATION must be relative to our people, i.e., history, culture, bilingual education, contributions, etc. Community control of our schools, our teachers, our administrators, our counselors, and our programs.

4.INSTITUTIONS shall serve our people by providing the service necessary for a full life and their welfare on the basis of restitution, not handouts or beggar’s crumbs. Restitution for past economic slavery, political exploitation, ethnic and cultural psychological destruction and denial of civil and human rights. Institutions in our community which do not serve the people have no place in the community. The institutions belong to the people.

5.SELF-DEFENSE of the community must rely on the combined strength of the people. The front line defense will come from the barrios, the campos, the pueblos, and the ranchitos. Their involvement as protectors of their people will be given respect and dignity. They in turn offer their responsibility and their lives for their people. Those who place themselves in the front ranks for their people do so out of love and carnalismo. Those institutions which are fattened by our brothers to provide employment and political pork barrels for the gringo will do so only as acts of liberation and for La Causa. For the very young there will no longer be acts of juvenile delinquency, but revolutionary acts.

6.CULTURAL values of our people strengthen our identity and the moral backbone of the movement. Our culture unites and educates the family of La Raza toward liberation with one heart and one mind. We must insure that our writers, poets, musicians, and artists produce literature and art that is appealing to our people and relates to our revolutionary culture. Our cultural values of life, family, and home will serve as a powerful weapon to defeat the gringo dollar value system and encourage the process of love and brotherhood.

7.POLITICAL LIBERATION can only come through independent action on our part, since the two-party system is the same animal with two heads that feed from the same trough. Where we are a majority, we will control; where we are a minority, we will represent a pressure group; nationally, we will represent one party: La Familia de la Raza!

Action

1.Awareness and distribution of El Plan Espiritual de Aztlán. Presented at every meeting, demonstration, confrontation, courthouse, institution, administration, church, school, tree, building, car, and every place of human existence.

2.September 16, on the birthdate of Mexican Independence, a national walk-out by all Chicanos of all colleges and schools to be sustained until the complete revision of the educational system: its policy makers, administration, its curriculum, and its personnel to meet the needs of our community.

3.Self-defense against the occupying forces of the oppressors at every school, every available man, woman, and child.

4.Community nationalization and organization of all Chicanos: El Plan Espiritual de Aztlán.

5.Economic program to drive the exploiter out of our community and a welding together of our people’s combined resources to control their own production through cooperative effort.

6.Creation of an independent local, regional, and national political party.

Figure 4. MEChA, Movimiento Estudiantil Chicano de Aztlán (Student Movement of Chicanos of Aztlán), is a national student group that grew out of the National Chicano Youth Liberation Conference in Denver, Colorado, March 1969, which also produced El Plan Espiritual de Aztlán (The Spiritual Plan of Aztlán). Its iconography features either a Mexican or American Eagle, with a macana (obsidian edged sword) in one claw and a stick of dynamite in the other. Mecha means “fuse” in Spanish. (Courtesy MEChA.)

A nation autonomous and free—culturally, socially, economically, and politically—will make its own decisions on the usage of our lands, the taxation of our goods, the utilization of our bodies for war, the determination of justice (reward and punishment), and the profit of our sweat.

El Plan de Aztlán Is the Plan of Liberation!

The Plan de Aztlán, which was written at the First Chicano National Conference in Denver, Colorado, in 1969, is the ideological framework and concrete political program of the Chicano Movement because of its emphasis on nationalism and the goal of self-determination. Source: Documents of the Chicano Struggle, Pathfinder Press, Inc. 1971. See figure 4 for iconography of MEChA, the Movimiento Estudiantil Chicano de Aztlán.

CHAPTER 2

AZTLÁN

A Homeland without Boundaries

THE CEREMONY OF naming, or of self-definition, is one of the most important acts a community performs. To particularize the group with a name is a fundamental step of awareness in the evolution of tribes as well as nations. The naming coalesces the history and values of the group and provides an identification necessary for its relationship to other groups or nations. Most important, the naming ceremony restores pride and infuses renewed energy, which manifests itself in creative ways.

I have reflected often during the last fifteen years on the naming ceremony that took place in the southwestern United States when the Chicano community named Aztlán as its homeland in the late 1960s. This communal event and the new consciousness and consequent creative activity which was generated within the Chicano community during this period marked an important historical time for our people.

The naming ceremony creates a real sense of nation, for it fuses the spiritual and political aspirations of a group and provides a vision of the group’s role in history. These aspirations are voiced by the artists who recreate the language and symbols which are used in the naming ceremony. The politicians of the group may describe political relationships and symbols, but it is the artist who gives deeper and long-lasting expression to a people’s sense of nation and destiny. The artists, like the priests and shamans of other tribes, express spiritual awareness and potential, and it is the expression of the group’s history, identity, and purpose which I label the “naming ceremony.” In the ancient world this expression of identity and purpose was contained in the epic; thus, we read Homer to understand the character of the Greeks.

Various circumstances create the need for national or tribal definition and unity. The group may acquire cohesion and a feeling of nationhood in times of threat, whether the threat be physical (war or exploitation) or a perceived loss of tribal unity. Group existence may also be threatened by assimilationist tendencies, which were a real threat experienced by the Chicano community in the 1960s. A time of adventure and conquest, or the alliance of political interests may also bring nations to self-definition. Most notably, times of heightened spiritual awareness of the group’s relationship to the gods create this sense of purpose and destiny in the community. Usually these times are marked by a renaissance in the arts, because the artists provide the symbols and metaphors which describe the spiritual relationship.

So it was for la raza, the Mexican American community of this country in the 1960s. This cultural group underwent an important change in their awareness of self, and that change brought about the need for self-definition. The naming ceremony not only helped to bond the group, it created a new vision of the group’s potential.

Where did the Chicanos turn for the content needed in the naming ceremony? Quite naturally the community turned to its history and found many of its heroes in the recent epoch of the Mexican Revolution. Some of us explored the deeper stratum of Mexican history, myth and legend. It was in the mythology of the Aztecs that the Chicano cultural nationalists found the myth of Aztlán. How did the content of that myth become part of the new consciousness of our community? That is the question which our philosophers have tackled from various perspectives, and it has been part of my preoccupation.

The naming ceremony, or redefinition of the group, occurred within the ranks of the Indohispanos of the Southwest in the 1960s. Leaders within the Hispanic community—educators, poets, writers, artists, activists—rose up against the majority presence of Anglo-America to defend the right of the Hispanic community to exist as a national entity within the United States. Two crucial decisions were made during this period by these guardians of the culture: one was the naming of the Chicano community, and the second was the declaration of Aztlán as the ancestral homeland. “Somos Chicanos” (We are Chicanos) declared the leaders of the nationalistic movement, and thus christened the Mexican American community with a name that had archaic roots. By using this term the Chicano community consciously and publicly acknowledged its Native American heritage, and thus opened new avenues of exploration by which we could more clearly define the mestizo who is the synthesis of European and Indian ancestry.

Figure 5. Anonymous, Siete cuevas de Chicomóstoc (Seven Caves of Chicomóztoc). Legend: “Cuevas de los siete linajes que poblaron en México” (Caves of the seven lineages that settled Mexico). According to origin stories, seven Náhuatl tribes once lived in the land of Aztlán at Chicomóztoc—“the place of the seven caves”: Acolhua, Chalca, Mexica, Tepaneca, Tlahuica, Tlaxcalan, and Xochimilca. (“Relation of the Origin of the Indians Who Inhabit This New Spain according to Their Histories,” 15...