![]()

CHAPTER 1

I Go Home

Kiev, Ukraine, 1918: The Ukrainian labor parties readied themselves for an armed uprising against the pro-German Skoropadskyi regime.1

Each of the labor parties created its own armed battle unit. We of the Bund assembled an armed unit of several hundred comrades. I was put in command, becoming a member of the Executive Committee (Ispolkom2) of the uprising.

The Bundist armed unit fought in the center of the city, occupying the quarter between the following streets: Kreshtchatik, Male Vasilkovske, and Fundekleyevske.

The success of the uprising brought the Ukrainian nationalist Vasylyovych Petliura3 to power, and, officially, the various political parties disbanded their armed party detachments. But in fact, every party—including the Bund—kept an organized core of its battle unit intact, just in case, as well as its store of arms.

The joyous mood of the Socialist parties after the uprising didn’t last long. The Petliura government lost no time in turning away from the labor parties that had helped bring it to power.

A telling incident: When Rosa Luxemburg and Karl Liebknecht were murdered in Germany, the Bund committee organized an open meeting to mourn and honor their memories. The Petliura administration forbade the gathering. I went to the offices of the administration to intervene, and to my great surprise met there with an official who had sat with me on Ispolkom just a short time ago. He ultimately withdrew the ban, but it left me with a very unpleasant feeling. Not very long ago we had fought side-by-side for the same goal; now we each of us stood opposed to the other.

The internal situation within the Bund itself also embittered our mood. The Bolsheviks were marching on Ukraine and approaching Kiev. The closer they came, the more our comrades appeared to give themselves over to the pro-Bolshevik view. But this was no longer simply a change of opinion, something we in the Bund were long accustomed to. This shift was something altogether new, and it was the chief cause of our bitterness. The Bundist comrade who became pro-Bolshevik did not simply change his opinion. He suddenly became unrecognizable, an altogether different person. In the factional fight, betrayal, trickery, and disloyalty became his weapons. Painfully we witnessed how the Bund spirit of comradeship, the feeling of belonging to one family, began to dissipate. In its place came distrust and suspicion.

In this situation and in this depressed mood, I attended a party meeting and listened to a report by Comrade Emanuel Nowogrodzki4, on a short visit from Warsaw. He talked about the revived Bundist movement in the new, independent Poland, and specifically, in Warsaw. He spoke about how the trade unions, now operating legally, had, as if overnight, branched out and grown. He told about the leading role the Bund played in these trade unions, about the Warsaw Labor Council and the important part the Bund played in that, and about the Bund’s many-branched cultural activities, centering around our Grosser Club.5 In passing, he spoke of comrades, the mere mention of whose names brought them vividly to mind for me. These were people with whom I was bound by many unforgettable moments of illegal activity during Czarist times.

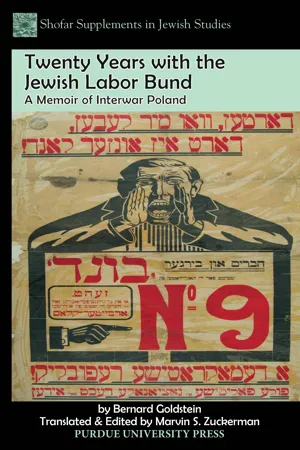

Figure 10. Emanuel Nowogrodzki (1947–1961). From the Archives of the YIVO Institute for Jewish Research, New York.

The picture that Comrade Emanuel painted captivated me. I imagined it all. I suddenly felt that the place Emanuel was describing was, after all, my home, and I was filled with a longing to return.

After the meeting, my mood, this sudden homesickness, grew even stronger. The report of a revived Bund in Poland sounded to me—here, in Kiev—like an idyll. The more I thought about it, the stronger my inner voice grew: Go home—now! Work in your own hometown Bund! Go where you will be battling with enemies of the working class, not with those who were your comrades only yesterday!

I decided to return to Warsaw. I went to the Kiev Bund offices to give my notice, submitting a report to the committee, and turning over all the bookkeeping items and party materials I had accumulated. I started preparing for the journey. My wife, Lucia, had just recovered from an illness. A very severe influenza epidemic was raging, and Lucia had contracted the disease. She had just started recovering, when we decided to go back home to Warsaw. Travel on the trains at that time was terribly risky for her. She was too weak to attempt such a difficult journey. We began to look for some other, more comfortable way for her to travel the distance, and suddenly, just such an opportunity presented itself.

Felye Kasel—the wife of the Yiddish writer, Dovid Kasel—and her sister, Pola, were living in Kiev at the time. They both worked for a large German company with a branch in Kiev. The company was leaving Kiev and arranging comfortable railroad cars for its staff. These two sisters were Lucia’s close relatives. After much effort they obtained permission for her to travel on this special train with them, so she was able to travel home quite comfortably. I remained in Kiev for a few more weeks, until I was able, as a Polish citizen, to obtain legal travel papers. I then started packing for the trip.

Actually, there was nothing to pack. I was dressed in an old military uniform, a long alpaca, and a pair of boots. Aside from those, I had only some underwear. I also took along a teakettle, a little sugar and tea, a spoon (just in case there was an opportunity to eat something hot), and a piece of soap. That was it. It was not a very heavy load. I did, however, end up carrying quite a heavy load, and one that was not even mine.

Right before my departure, Shuel Kahan, a brother of our comrade Virgili Kahan6—a one-time “United,”7 now a Bundist—approached me and requested that, since he had heard I was traveling to Warsaw, and since his family members, who were in Lodz, were also traveling back home to Warsaw, would I please help them out with some luggage? I agreed. These people—I forget their names, Silverberg or Silvermintz—had two very heavy valises. I helped by carrying one of their valises as my own luggage. We couldn’t all fit into one railroad car, so I went off by myself with my small bundle and their heavy valise. They sat separately in another compartment.

The journey was difficult. Trains were few and far between and ran irregularly. The individual train cars were also few, unheated, broken down, and packed full of people. Entire families with all their belongings were traveling in all directions, running from city to city, seeking some out-of-the-way, secure spot to settle. When the steam locomotives ran out of fuel, as happened often, the trains would stop in the middle of nowhere. The stokers would run over to a nearby forest, chop some wood, feed the locomotive, and then proceed a bit farther. Trains would often have to stand waiting for a long time. If the passengers were lucky, another train would come they could transfer to and continue their journey. We dragged on in this way from Kiev to Warsaw for ten days. In normal times such a journey would have taken around 24 hours.

The family whose valise I was carrying took very good care of me the whole time. They would often come into my railroad car to see how I was doing, bringing me a piece of bread and some tea. After a time, this attentiveness seemed somehow excessive. When we arrived at Otwock, near Warsaw, I had to leave the train for a moment. The train started to move, and I was unable to jump back on in time. Seeing this, the family became frantic. I shouted at them to wait at the next station, and I would join them with the next train (trains were running frequently from Otwock to Warsaw). I did in fact catch the next train, and there they were, waiting for me at the next station. They thanked me profusely for my help and asked me to please accompany them to the hotel.

We got into a droshky8 and were on our way.

I was greatly astonished to see they were going to the Hotel Bristol, the most elegant hotel in Warsaw. They checked into a suite of rooms. I went with them. They opened the valises, and I grew dizzy at the sight. The valise they had asked me to carry for them had a false bottom, in which lay gold and jewelry and other expensive luxury items. They offered me several hundred marks for my trouble. I answered that if I were willing to be paid, my due would be half the value of the items I carried, but that I wanted nothing from them. I left their hotel room without a goodbye.

For a long time afterward I could not forgive myself for taking such a dangerous mission so lightly. The inspectors on the trains were then very strict, especially with evacuees from Russia. Had they caught me smuggling such a valise, I would have been in a great deal of trouble.

Notes

1.Skoropadskyi (1873–1945), aristocrat, decorated Russian and Ukrainian general; in 1918 led a coup d’etat, sanctioned by the occupying German army, against the Ukrainian People’s Republic, becoming the reactionary, autocratic leader of the Ukraine.—MZ

2.Russian abbreviation for Ispolnitelniy Komitet, “Executive Committee,” the lead organization consisting of representatives of all the Ukranian labor parties, as well as the illegal, military party cadres.—MZ

3.Vasylyovych Petliura (1879–1926), publicist, writer, journalist, Ukrainian politician, statesman of the Ukrainian People’s Republic, and national leader who led Ukraine’s struggle for independence (1918–1921) following the Russian Revolution of 1917. On May 25, 1926, Petliura was slain with five shots from a handgun in broad daylight in the center of Paris by the Jewish-Russian anarchist, Sholem Schwartzbard, to avenge Ukranian pogroms against the Jews.—MZ

4.Emanuel Nowogrodzki (1891–1967): General Secretary of the Polish Bund’s Central Committee. In America by chance in 1939 when the war broke out. Founded the Bund Representation and the Bund Coordinating Committee in America. Editor and writer for the Bund’s monthly in New York, Undzer Tsayt. Author of The Ghetto Speaks (Warsaw, 1936?); Individual, Rank and File, and Leader (Warsaw, 1934); Henryk Erlich and Victor Alter (1951); and The Jewish Labor Bund in Poland 1915–1939 (2001), later translated into Polish as Żydowska Partia Robotnica Bund w Polsce 1915–1939 (2005).—MZ

5.Named after Bronislaw Grosser (1883–1912), a Bundist writer and theorist on Jewish nationalism. A lawyer by profession, he was recognized as one of the party’s most articulate defenders of Jewish national-cultural autonomy. Defining himself as a Polish-Jewish Socialist whose task it was to defend the interests of the Jewish workers in Poland, he became a Bundist legend, with several cultural, educational, and health institutions established in his name in interwar Poland, including the Bund’s renowned Bronislaw Grosser Library in Warsaw.—MZ

6.Borukh Mordkhe Kahan (Virgili), 1883–1936; beloved Bundist activist and labor leader; also active in organizing and supporting the Yiddish secular school movement; 20,000 Jewish workers attended his funeral in Vilnius.—MZ

7.United: A member of the Fareynikte Yidishe Sotsyalistishe Arbeter Partey (United Jewish Socialist Workers Party), a unification (fareynikung) in 1917 of the Zionist Socialist Workers Party and the Jewish Socialist Workers Party. The Uniteds, like the Bund, believed in fighting for civil rights and cultural autonomy in Poland and the Ukraine, but also, unlike the Bund, in seeking to create a Jewish state in any available territory (not necessarily in Palestine).—MZ

8.Droshky: a low, four-wheeled, horse-drawn, open, passenger carriage.—MZ

![]()

CHAPTER 2

Back in Warsaw

Upset, I left the hotel and started walking. With my small bundle in my hand, I walked in the direction of Nowolipie 7, the editorial offices of Lebns-Fragn, the Bund’s daily newspaper. As I walked, I looked around at the streets of Warsaw. They made an awful impression. Warsaw was somehow darker, greyer, the streets neglected, the houses shabby, gloomy. I had not seen her since the prewar years. The city appeared to be terribly neglected.

Now I found myself at the end of Długa Street. I trembled. At this spot was the jail, the so-called “Arsenal.” Over four years ago they had led me out of there in chains, when I, together with Yankl Levine and several hundred other political prisoners, were exiled deep into Russia. On this street my wife, Lucia, had waited for me, along with Comrade Mania Majerowicz (now Mania Mayer, in New York), Czilba Krisztal (now in Melbourne, Australia), and others. Here is where we left Medem1 behind, sick and in the hospital. Now I pass that same “Arsenal,” free, unshackled, and without fear. It is different now, Warsaw.

I turned down the little way from the crossing and was already at Nowolipie 7, at the Lebns-Fragn building. I went up to the fifth floor, entering the editorial offices....