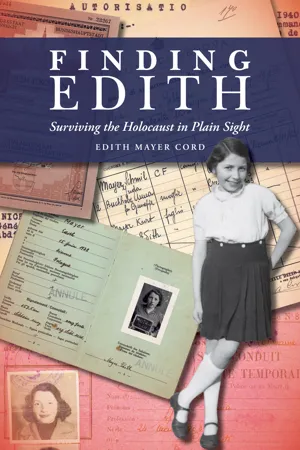

![]()

Beginnings

1. VIENNA, AUSTRIA

My Childhood and Early Memories

As a child, I wanted to be like everyone else. As an adolescent, I yearned for schooling. As a young adult, I just wanted to lead a normal life. In old age, I hoped that the terrible lessons of the Holocaust would be learned and that anti-Semitism would be a thing of the past.

I’ve come a long way since my childhood in Vienna, where I was born. My parents came from the eastern fringe of the great Austro-Hungarian Empire. Until 1914 both of my parents were living with their families in Czernowitz, then part of the Empire, near the Russian border. Czernowitz had been the capital of the Duchy of Bukovina, annexed as a crown land by the Austrian Empire after the upheavals of the 1848 revolutions in Europe. German was the official language, and my parents and their siblings went to German-language schools. My mother told me that the local population spoke Ruthenian. The city was a major transportation hub and a prosperous commercial center. My mother often talked about the lovely river Prut. Newer buildings reflected the Austrian influence of the Jugendstil or art nouveau. After World War I, the province of Bukovina with its capital of Czernowitz became part of an independent Romania. The region was annexed by the Soviet Union after World War II. Today, Czernowitz is part of southern Ukraine.

Shortly after World War I broke out, both families fled to Vienna to escape the advancing Russian troops. My mother, born in 1903, was twelve years old. Her three older brothers were drafted and served in the Austrian army as officers. Karl, the youngest, was killed in 1916 in Italy, a loss from which neither my grandmother, Rosa, nor my mother ever recovered.

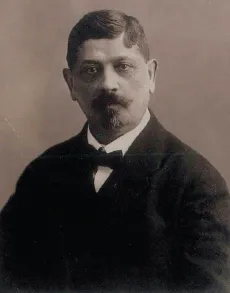

My maternal grandfather, Josef Buchholz, was a sophisticated and handsome man with dark eyes and a stylish goatee. Though he had his rabbinical ordination, he never used the title of rabbi. He made his living as a wholesale food merchant, trading sardines by the wagonload, grain by the ton, chocolate and other foodstuffs by the box and barrel. Later, I learned that Jews had lived as merchants in Czernowitz for centuries. Before World War I the Jewish population numbered about 30,000 or one-third of the total population in town. It was a prosperous community judging by the imposing Moorish revival synagogue (now destroyed) and by what is now the Palace of Culture, originally built to serve as the Jewish National House. The rest of the population was made up of Germans, Poles, Romanians, Ukrainians, and more, all living together under the rule of the Austro-Hungarian monarchy. After World War II, members of those different ethnic groups were chased out by the Soviets, with Germans sent to Germany, Poles to Poland, and so forth until only Ukrainians remained.

My mother’s family had servants and their standard of living was high. German was spoken at home and all the children attended German-language schools and universities. My grandfather was a highly respected member of the community and the family had what is called yiches, Yiddish for ancestry, family status, and prestige.

I suspect the standard of living in my father’s family was more modest. My father was the oldest of eight. He was born in 1888 in Horodenka, a small town close to Czernowitz, also within the borders of the Austro-Hungarian Empire. My father was named Schmil Juda, but everyone called him Adolf, a popular name at the time. When my father was one year old, his family moved to Lemberg, now Lviv. When my father was twelve years old, his family moved to Czernowitz where my paternal grandfather opened a clothing store that my mother’s family patronized.

Papa’s father, Josef Mayer, had a limited command of German. When still a boy, he tried to teach himself the alphabet, but he was caught by my great-grandfather who ripped up the book saying, “Du wirst dech schmatten!” (“[If you learn German] you will convert!”). But my grandfather was literate in Hebrew and read the Yiddish newspaper while his written German remained weak. He made amends for what his father had done to him by ensuring that Papa received an excellent secular education. In addition to the required eight years of schooling, my father went to a business academy for four years. As a result, Papa had an excellent command of German and a solid general education. At home, the family spoke mostly Yiddish.

Papa was on the short side with a round face, blue-gray eyes with glasses, very white skin, a high forehead, and thinning blond, straight hair. He was clean-shaven, except for a little, stylish, closely trimmed moustache. As the oldest, Papa often commented that he did not want to have so many children for then they raise themselves. He was very close to his father, which led to resentment among the other siblings (something I learned recently from my Uncle Michael’s grandson, Ilan).

When the war ended, Mama’s situation in Vienna became precarious. Her father decided to go back to Czernowitz, which had become part of Romania, to see whether anything was left of the family estate. He took his middle son Leon with him and in 1920, while there, my grandfather died of a heart attack. Leon chose to stay in Czernowitz and married a woman named Klara. They had three children: Josef, Rosa, and Karl. In 1918, Mama was left in Vienna with her mother and her oldest brother, Rudolf, who was thirteen years her senior and in his early thirties. They were still living in the same apartment they had occupied during the war. It was on the fifth floor of a nice building in the first district—Werdertorgasse number 17—near the corner of Franz Josef Kai and the Danube Canal.

Vienna was the capital of the once sprawling, multilingual Austro-Hungarian Empire, which was reduced to its German-speaking part after the war. This was the result of President Wilson’s Principle of Nationalities, according to which each ethnic group was to have an independent country of its own. That resulted in the dismemberment of the old Empire, leaving in its place small, independent political entities that were not economically viable. This void contributed to the economic weakness and eventual collapse of Central Europe, a decline that opened the way for the totalitarian regimes that followed.

After World War I there were approximately 200,000 Jews living in Vienna, about ten percent of the total population. My family lived in the first district in the heart of Vienna, an area dominated by the soaring Stefansdom (St. Stephen Cathedral) and surrounded by the Ringstrasse where once the city’s walls had stood. Now the Ringstrasse was dotted with imposing buildings including the Parliament, the university, the Hofburg (royal palace), two famous museums, the graceful opera house, the Rathaus (city hall) with its gothic spires, the Stadtpark (city park) and its romantic monument of Johann Strauss Jr., all reflecting the city’s neoclassical architecture with imposing columns and statues on top of public buildings. The Jews living in the first district were more assimilated than those living in the second district, which had been given to Jews by King Leopold and was known as the Leopoldstadt. In the heart of the first district was the Judenplatz, the center of the old Jewish Ghetto. When I was five years old, Mama told me that was where they burned Jews in the Middle Ages. And so from early on, I was aware that we were a persecuted minority.

While it is true that Jews were discriminated against and persecuted throughout the Middle Ages and later, the actual burning was done in another location. Both in Vienna and throughout Austria, there had been a series of pogroms over the centuries. These persecutions had some economic motivations, but sadly, they were also the result of the Church’s teachings. My reaction to Mama’s comment? “I’m glad they don’t do that anymore.” Little could I know what the future would bring.

Edith’s maternal grandfather, Josef Buchholz. Photo taken in Vienna, ca. 1918.

When her family moved to Vienna, Mama was sent to a Pensionnat, a private girls’ school, until she was sixteen. In 1919, Grandmother Rosa died of the Spanish flu in the epidemic that killed millions, leaving Mama orphaned and destitute. She had a bourgeois education, knew how to play the piano, spoke some French, and could embroider beautifully, but she had neither marketable skills nor money. The expensive life insurance policy my grandfather had bought to protect her was paid, but the money was worthless because of the inflation raging in Austria. From my mother’s sad experience, I learned the importance of acquiring skills to support myself.

Mama’s brother Rudolf, together with her legal guardian whose name I never learned, focused on finding Mama a husband. The story she told me was that a Shiddech (match) was arranged with an older man who had money. They got engaged, but the engagement was broken by the groom. To compensate my mother, he gave her a substantial sum of money as a quit claim. As a result, Mama boasted that she was a rich girl.

My parents met in Vienna after the war at a party given in honor of one of Papa’s sisters on the eve of her wedding. Mama was just seventeen years old. Papa was thirty-two and was being pressured by his family to take a wife. I don’t think there was great passion on either side. Mama said only that she liked him, which was very different from the teenage crush she had on a distant cousin, according to the stories she told me. My father was obviously ready to marry and would often joke that he had searched for her with great care. My mother came from a good family, and that must have settled the match.

Edith’s paternal grandfather, Josef Mayer, and grandmother, Rifka Rachel Mayer, née Halpern, Vienna, 1920s.

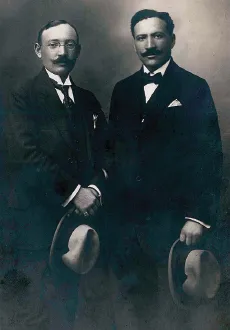

Edith’s father and his brother, Michael, Vienna, ca. 1918.

After Grandmother Rosa died, Mama continued to live in the apartment with Rudolf, but when he got engaged, he wanted the apartment to himself. Right after my parents’ engagement, Rudolf locked Mama out of the apartment. The story I got from my mother was that she was forced to spend the night sitting with Papa on a park bench. Papa took Rudolf to court, which did not improve family relations, and in the end, the two couples were forced to share the apartment. Needless to say, it was not a harmonious relationship.

Edith’s parents’ wedding picture, November 1921, Vienna.

My parents were married November 6, 1921; Mama was eighteen and Papa was thirty-three. According to Mama, after they were married, Papa visited his parents every night, leaving her alone. She interpreted this as the result of his excessive devotion to his father. Initially I accepted Mama’s view of things, but now I wonder if Papa was happy with his young wife. He was fifteen years her senior, a sophisticated and elegant dandy. Mama was an inexperienced young girl with a limited education and a sheltered upbringing. I also suspect that, at least initially, my parents may have quarreled because, again according to Mama, Papa said, “Do you want to quarrel like your parents did?” By the time I was old enough to understand, I never heard my parents quarrel or even raise their voices to each other. When once asked about my parents in school, I remember saying that they got along like two turtle doves. On March 10, 1923, a year and a half after their marriage, my brother Kurt (Mordechai) was born. I came along in 1928, on June 15, and yes, we all still lived in that same place.

Our apartment was in a very nice building in the newer section of the first district. By modern standards, the apartment had its limitations. There was a cold water faucet on the landing that served all the apartments on the floor. Inside there was a long hallway. To the left was a toilet used by both families. On the right was a door that led to two rooms occupied by Uncle Rudolf and his wife, later joined by their daughter Alice, nicknamed Lizzy. Mama liked Lizzy, she said, because Lizzy looked like her. Straight down the hall was another door leading to two more rooms occupied by my parents and eventually Kurt and me. Our windows opened onto an inner courtyard, kitty-corner to my uncle’s windows, so the families could hear everything going on in the other’s living quarters. The families never spoke to each other. As a child, I was well aware of the animosity between the families since their mutual dislike and contempt permeated the atmosphere.

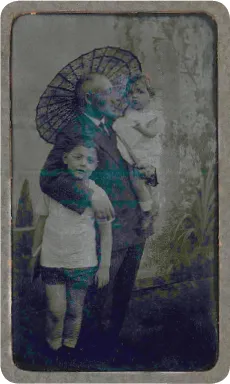

Papa, Kurt, and Edith. The caption reads, “Papa and our dear little children,” Vienna, 1929.

When Mama got engaged to Papa, she’d given him her dowry and, according to her, he’d spent it all setting up his father in business. She resented that. In addition, Mama’s relationship with Papa’s family was a disaster. She despised all of them and had nothing good to say about any of them, with the exception of my father’s sister Anna who died in childbirth soon after my parents’ wedding. As for the rest of the family, almost all were very well-off while my family was not. The fact remains that we never socialized with my paternal aunts, uncles, or cousins or got invited to birthday parties, bar mitzvahs, and other life events. Our only contact was through my grandparents or when Mama needed something. Once when we visited an uncle’s store, one of my aunts greeted us with, “What brings you here?” Mama took offense and never let it go. So when Mama kept telling me that I looked like Papa’s sisters, it was not meant as a co...