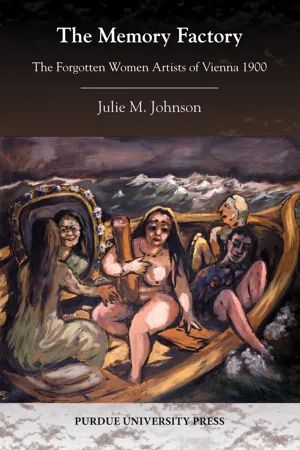

![]()

Writing, Erasing, Silencing: Tina Blau and the (Woman) Artist’s Biography

Impressionist Tina Blau (1845-1916) painted aesthetically innovative works, like the 1898 View of Vienna, in which she allows the paint to hover over the canvas, the brushstrokes and color taking precedence over the figures and landscape that they represent (fig. 3). Cultural critics Karl Kraus (1874-1936), Rosa Mayreder (1858-1938), and Adalbert Franz Seligmann (1862-1945) all recognized the very aesthetically advanced, modernist qualities of her painting. At the turn of the century, she was a famous artist, her paintings in the court collections and sought after by women artists’ groups. After 1938, Blau would be temporarily erased from Austrian art history because she was a Jew. Because her reputation was so well established (and she died in 1916), the erasures of her artistic record can be tracked, and her reputation has been restored. Yet despite the fact that Blau has been celebrated in a 1996 exhibition at the Jewish Museum in Vienna (another significant instance of identification and recovery of lost artists based on their Jewish identity), she remains little known outside Austria.1

Her story offers ample documentation through which to examine the silencings of a modern woman artist’s life—one omitted from the Secession’s selective ancestor cult in her lifetime and literally erased from public spaces through institutionalized anti-Semitism in the late 1930s. Instead of being celebrated as a precursor to the modernist values of the fin de siècle, Blau was mistakenly called a student of her male peer, Emil Jakob Schindler, which placed her in the role of follower rather than independent discoverer. Blau had a significant public exhibition record and was both critically and commercially successful, drawing considerable envy from her male peers and especially her teacher August Schaeffer when she had a series of one-person shows and a large auction. Such stories remain buried in Vienna 1900 studies, not only because of gender prejudice, but also because few have written about the role that art dealers played in the art historical field, which has focused primarily on the Secession, Künstlerhaus, and Hagenbund—all publicly funded artists’ organizations that excluded women from officially joining.

Fig. 3. Tina Blau, View of Vienna, 1898. Oil on wood, 21 x 28 cm. The Eisenberger Collection, Vienna. Photograph © Vera Eisenberger KG, Wien.

The Secession had the most elaborate exhibition program of modernist art, complete with visiting lectures from art historians Julius Meier-Graefe and Richard Muther, creating its own ancestor cult. Blau possessed all of the characteristics of an artist who would have been celebrated by a younger generation of artists (the Secessionists) in her hometown of Vienna. She was stylistically innovative, had a confrontation with the local Künstlerhaus for being too progressive, and achieved early success on foreign soil. But the Secessionists did not celebrate her in their ancestor cult because she was a woman, and the “mother-son plot,” a source of discomfort in Freud’s Vienna, indeed remains so today in art historical narratives.2 She herself managed her career by withholding aspects of her identity—she refused to exhibit with women’s artist associations, for example, and did not actively intervene into the formation of a public record of her life until she was fifty. She nevertheless negotiated a very successful career, exhibiting in numerous one-person shows in Vienna and Munich, winning financial independence early on, and cultivating a circle of sympathetic critics. After her death in 1916, there were numerous celebrations of her life, and by 1933 there was a retrospective of her art in Vienna, but by 1938, the street that had been named after her was renamed, and she was literally erased from the histories of Austrian art, her paintings removed from the galleries, all for being a Jew. Her story demonstrates the significant role that biographical facts play in securing the memory and reputations of artists, and how vulnerable women especially have been with regard to moments of silencing and erasures.

One of the biggest problems with biography for women has been its continuing susceptibility to distortion. As Kristen Frederickson has pointed out in Singular Women: Writing the Woman Artist, the survey writers Janson and Janson (in their very brief and recent inclusions) included anecdotes about Elisabeth Vigée-Lebrun’s personal beauty and Artemisia Gentileschi’s feelings about men, while doing no such thing for Caravaggio or other male artists.3 Frederickson’s concern was prefigured in debates among art historians at the turn of the previous century, albeit for reasons of method rather than concerns for gender equity. Heinrich Wölfflin and art historians at the Vienna School rejected the sort of history that Richard Muther (1860-1909) had written with The History of Modern Painting, a popular art history survey text that was widely translated. The scholars at the Vienna School found Muther’s writing irredeemably sentimental because of its dependence on anecdotal biography in the narrative. Muther equated works of art with the physiognomies and personalities of their makers, sometimes in quite inventive ways: “Andreas Achenbach’s forehead, like Menzel’s, is rather that of an architect than of a poet; and his pictures correspond to his outward appearance.”4 Alternately, he would embellish preexisting characterizations of artists like Gustave Courbet, who was “himself the ‘stone-breaker’ of his art, and, like the men he painted, he has done a serviceable day’s work.”5 Muther turned artists into signposts in a diverting narrative, but rarely included women.

Instead of temperament and character, Wölfflin made aesthetic, formal concerns the basis for a “scientific” study of art history. In “Rigorous Study of Art,” a review essay published in 1933, Walter Benjamin agreed with Wölfflin’s dismissal of Muther’s version of history:

Frederickson, Wölfflin, and Benjamin share a concern for the misuse of biographical facts to explicate pictures or conflate aesthetics with personal fortune. But biography is nevertheless essential as a parallel, intertwining text to the works, for securing the memory of an artist. For an artist to receive wider attention, the repetitions, or the “echoes” of history, as Joan W. Scott wrote, are necessary for securing that reputation. To expect aesthetics alone to inspire the continued attention that Scott describes has rarely, if ever, worked.

In 1982, Linda Nochlin posed the correlative question to her “why have there been no great women artists?”—namely, “why have there been great male artists?” She investigated the biography of Courbet to demonstrate how his politics were circumvented (or celebrated, in one case) through various narrative strategies in Third Republic France. Nochlin meant to demonstrate that the biography of the artist presents not a set of explanatory facts, but rather an infinite range of materials from which to tell a story—it is as much an art form as is the work of art itself, and a component in securing the memory of the great artist.7 Ernst Kris and Otto Kurz had already suggested in 1934 that rather than merely providing an entrée into the mind of the artist and therefore the work, the artist’s biography was a sociological phenomenon, that certain stereotypes prefigured the narratives which were sought out, recorded, and even invented about the artist.8 These are the repetitions and identifications that secure reputations over time. While Nochlin made her point by examining different readings of Courbet, the authors of which rescued him from his disastrous episode during the French Commune, women artists rarely present such case studies. Rather, historical silencings, careful self-presentation, and negotiations of fraught institutional fields more often form the raw materials of women artist’s biographies.

The artist’s public self-presentation, or lack thereof, is important material for prospective biographers. Blau tried, sometimes in vain, to place her work first, and to remove her biographical identity from its reception, for she was keenly aware of the ways in which women’s art was misread in fin-de-siècle Vienna, where art historical narratives of influence and generational metaphors were employed both within the new school of art history and by artists of the Secession. In the history of art, artists play a significant role in canon formation not only when they choose their own precursors, but also when they document their own lives. Art historians produce the more official histories, but the role that nonhistorians play is equally important to recognize. Blau waited until she was in her fifties to make corrections about her life story. Michel-Rolph Trouillot has proposed that silencing the past is an active process, and argues there are “many ways in which the production of historical narratives involves the uneven contribution of competing groups and individuals who have unequal access to the means for such production.”9 A. F. Seligmann, Blau’s colleague at the Art School for Women and Girls, and her greatest champion, summarized the situation in an exhibition catalogue shortly after Blau’s death:

Silences in history are difficult to recover, but Seligmann bridged some of the early gaps with his consistent championing of Blau.11

Artists’ participation in ...