![]()

Part one

IP potential

![]()

1.1

Europe’s capacity for innovation

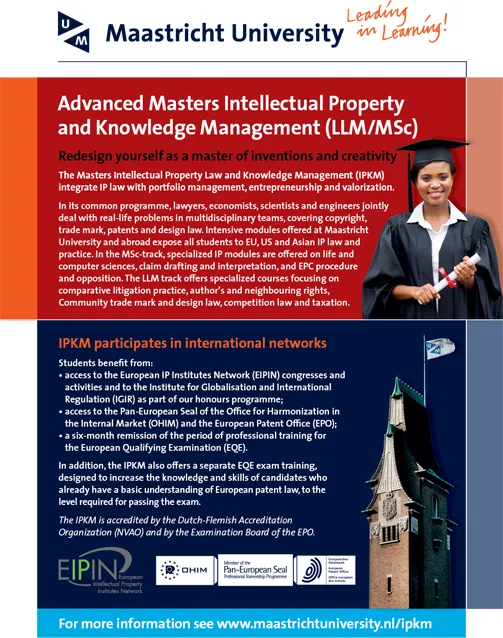

Anselm Kamperman Sanders and Meir Perez Pugatch at Maastricht University review the uneasy journey that European innovation and IP policy are taking from the Lisbon Agenda to Horizon 2020.

Innovation, innovation, innovation. Everyone, including the EU, talks about innovation as the ‘holy grail’ of economic development. But does the EU practice what it preaches? A simple question with no easy answer. And throwing the question of intellectual property (IP) and its role into the mix only further complicates the discussion.

Nevertheless, we shall try to provide a concise take on the state of innovation in Europe, and on the manner in which the EU has tried to align – with limited success – its IP policies with its broader vision on innovation.

Why focus on innovation: from the Lisbon Agenda to Horizon 2020

In ‘Putting knowledge into practice: A broad-based innovation strategy for the EU’ (2006),1 the European Commission acknowledged the importance of innovation for Europe’s future. In doing so, it made the point that tackling the issues of climate change, depleting national resources, sharp demographic changes and emerging security needs were all reliant on Europe’s ability to harness innovation. It also emphasized Europe’s strong tradition of innovation and the way in which the internal market allows innovative products to be commercialized on a large scale. Indeed, it argued that the wealth of creativity across Europe and the strength of cultural diversity must be capitalized on to not only overcome significant obstacles, but to also allow Europe to compete globally with the world’s biggest economies.

To achieve this the Commission pointed to a comprehensive strategy for modernizing the European economy, focusing on the path created by the Lisbon Strategy for Growth and Jobs.2 Established in 2000, the Lisbon Strategy aimed to make the EU the ‘most dynamic and competitive knowledge-based economy in the world’ by 2010. It acknowledged the importance of research and innovation and provided a blueprint of key policy instruments that need to be implemented in order to meet this objective, including increased investment in R&D, reduction of red tape to promote entrepreneurship and measures for achieving an employment rate of 70 per cent.

Coming back to 2015, whilst it is quite clear that many of these targets have not been met the Commission has maintained that it would be simplistic to conclude therefore that the Lisbon Strategy has failed. Instead it pointed out that the success that was achieved in terms of breaking new ground and promoting common action to address the EU’s key long-term challenges has provided the European Union with a platform to build upon.3

This is the task of Europe 2020,4 the successor to the Lisbon Strategy initiated in 2010. Europe 2020 highlights the increasing need to create new jobs to replace those that were lost during the financial crisis. It also reaffirms the EU’s conviction that innovation and creativity are the best means of successfully tackling major societal challenges, even as they become more urgent by the day. As part of the Europe 2020 Strategy, the European Commission has set out several key drivers for growth in the economy over the decade, in particular the need for smart growth that fosters knowledge, innovation, education and a digital society. As one of seven flagship initiatives announced under this new strategy, the hope is that the EU would develop a true ‘Innovation Union’ by 2020, one with improved conditions for innovation and where innovative ideas can be turned into products and services that create growth and jobs.

Innovative, but not enough!

To its credit, the EU certainly understands the downside of not being innovative enough.

Indeed in one of the most important studies in this area, ‘The costs of a non-innovative Europe: The challenges ahead’ (2010),5 Professor Luc Soete of UNU-MERIT attempted to better understand the macroeconomic impact of innovation policies (as well as those not supporting innovation) included in the Europe 2020 agenda. The study considered three growth scenarios for the period 2010–2025. The first was based on current economic forecasts, the second on forecasts before the financial crisis and the third on a scenario in which the EU as a whole raised R&D spending to 3 per cent of GDP from 2010 onwards. The simulation showed a severe gap between pre-crisis economic forecasts and current forecasts – the long-term structural gap in the EU’s GDP is on average some 9 per cent. Yet, the modelling also shows that by boosting R&D spending the EU could recover 45 per cent of this gap by 2025. Similarly, a rise in R&D spending is associated with a complete recovery of the employment gap between pre-crisis and current forecasts by the end of 2015, with 3.7 million jobs created by 2025.

Paul Zagamé’s follow-up paper, entitled ‘The cost of a non-innovative Europe: What can we learn and what can we expect from the simulation works’ (2010),6 reinforced the results made in Soete’s paper and concluded that because innovation spending is pro-cyclical it needs to be supported during times of crisis because its weakness could cause further damage.

What both of these reports, as well as the Europe 2020 agenda in general, show is that innovation is fundamental to the growth of the European economy and that, in the context of the financial crisis, it has never been so important. Whilst there are undoubtedly long-term benefits for Europe in utilizing innovation, the short-term needs of the European economy now make such policies essential to encouraging growth and creating more jobs.

But how innovative is Europe actually? The 2014 ‘EU Industrial R&D Investment Scorecard’7 seems to provide us with a good answer. The report suggests that, despite improving its overall innovation performance, the EU as a bloc is still lagging behind the other top innovators such as the United States, Japan and South Korea. Moreover, the report suggests that within Europe there are still significant gaps between the top innovative countries (Sweden, Denmark, Germany and Finland) and innovation laggards (Bulgaria, Latvia and Romania). The report notes that ‘particularly large differences are in the international competitiveness of the science base (Open, excellent and attractive research systems), and business innovation cooperation as measured by Linkages & entrepreneurship’ (p 6). The 2013 joint study of the OHIM and EPO entitled, ‘IPR-intensive industries: contribution to economic performance and employment in the European Union’,8 also provides interesting insights into the development potential of the EU. The differences in national European innovation levels lead to a situation where technology transfer from top innovators to other EU Member States may have a real and immediate impact on overall EU growth. Increasing the absorptive capacity for technological development of ‘innovation followers’ and, even more importantly, innovation-dependent Member States is therefore necessary to bring about such positive effects. Enabling intra-community technology transfer should therefore be prioritized.

Harnessing the power of IP, but also understanding its limitations

So what do IPRs have to do with innovation, not least in the European context?

We do not have enough space to dwell on the structural and macroeconomic effects of IPRs, but suffice it to say that IPRs are aimed at solving a unique market failure that can slow down, at times even significantly, the rate of innovation.

In their more basic forms IPRs fulfil three basic functions: the ‘creation of competitive markets’ for human, industrial and intellectual creativity that is novel or original, where consumers can make rational choices about which goods or services to buy; ‘insurance’ to innovators, safeguarding the fruits of their labour from abuse by free-riders; and a ‘commercial gateway’ through which innovators can exploit and benefit from their creations.

Naturally, IPRs also have limitations and boundaries, not least the problems that may arise due to the considerable market power that IPRs provide to their owners.

Thus, European IP policy seeks to build upon the innovative and creative potential of its citizens, whilst maintaining the necessary social safeguards that are intrinsic to any form of IPR.

In this context, the EU currently faces several challenges when shaping its IP policy.

We should begin, however, by underscoring where the problems do not seem to lie. As a whole the EU’s level of IP protection appears to be securely at the top. The third edition of the Global Intellectual Property Center International IP Index found European countries to have some of the highest levels of intellectual property protection, including in the area of enforcement.9

The issue is therefore not about increasing the level of IP protection in the EU, but rather about making better use of the system, across ...