![]()

1

THE MUCH -MALIGNED LEGISLATIVE BRANCH

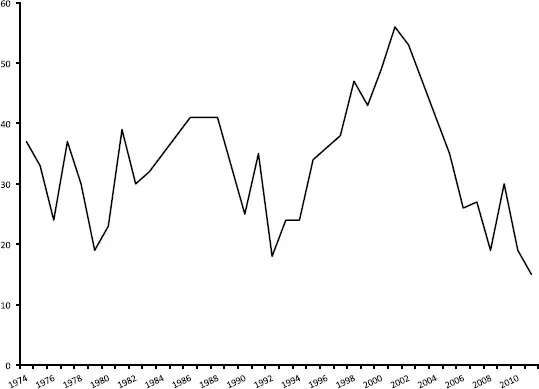

Congress is extremely unpopular. In the months leading up to the 2010 midterm elections, only about 20 percent of Americans approved of the job the institution was doing. Several polls that spring had the figure as low as 15. This put Congress well behind the other branches of government—President Obama’s job approval was around 45 percent, the Supreme Court’s somewhere in the mid-50s. Gallup reported consistently during the summer and fall of 2010 that about 60 percent of Americans—the highest proportion on record—believed most members did not deserve re-election. A March 2010 poll undertaken by the Pew Research Center for the People and the Press asked 749 Americans to provide one word that best described their current impressions of Congress. Eighty-six percent offered something negative; “dysfunctional,” “corrupt,” and “self-serving” were the top three responses.1 The opprobrium did not distinguish by party. A September 2010 Gallup poll revealed 33 percent of Americans approved of the job congressional Democrats were doing, 32 percent that of congressional Republicans. A grassroots Internet-based movement led by groups like Get Out of Our House called on voters to defeat all incumbents who were running for re-election.

If anything, matters worsened after the election. During the busy lame-duck session in December, Congress had reached its lowest level of public support since Gallup had begun surveying Americans on the topic in 1974.2 Although the House came under Republican control after the party, in the words of President Obama, “shellacked” the Democrats and picked up sixty-three seats, the general dissatisfaction continued at historic levels during the early months of the 112th Congress. When the Obama administration and congressional Republican leaders warred over an extension to the nation’s borrowing authority in the summer of 2011, 77 percent of respondents to a CNN/Opinion Research Center (ORC) poll described the principals’ behavior as being like that of “spoiled children”; only 17 percent felt they had acted as “responsible adults.”3 In September 2011 only 12 percent of respondents to a CBS News/New York Times poll said they approved of the job the institution was doing; with the economy still extremely sluggish the figure reached a miserable 9 percent in October. According to Gallup’s poll the rating recovered only slightly in the spring of 2012, by which time a political action committee (PAC) called the Campaign for Primary Accountability was diligently raising money to purge the House of its incumbents.4

It has not always been this way. As Figure 1.1 demonstrates, approval ratings were similarly low for a short while in the late 1970s and early 1990s, but at that time the public lacked confidence in just about all public officials—Jimmy Carter’s and Bill Clinton’s approval ratings were about fifteen percentage points lower than Barack Obama’s scores—and the intensity of the hostility to Congress was short lived.5 In the aftermath of 9/11, moreover, there was some hope the federal legislature would again be seen as a body fit for the world’s greatest democracy. Whether the result of Congress’s defiant response to its selection as an Al Qaeda target or its swift action on a variety of proposals to put the country back together again and send it off on the trail of terrorists, the institution’s public approval rating climbed as high as 84 percent in a Gallup poll of late 2001. That seems such a long time ago now. By contrast, the public’s current mood is especially dark. It does not much like its political leadership and clearly Congress is a particular object of its anger.

It is also not like this elsewhere. Although citizens across the world tend to hold their parliaments in lower esteem than they do their civil services and military institutions, support for the work of legislative bodies is higher abroad than it is in the United States. Since 2006 the World Economic Forum has reported that business executives in Canada, Germany, and the United Kingdom all rank their parliaments as more “effective” than do their counterparts in this country. The World Values Survey taken in the middle part of the last decade revealed approximately 30–40 percent of respondents in western European countries had a “great deal” or “quite a lot” of confidence in their national legislature. This was about double the figure for Americans and Congress (Griffin 2010, 362).

Why Americans Dislike Congress

Scandal and More Scandal

For most of us, it is not difficult to understand why Congress generates these feelings. It seems perpetually mired in scandal. Every time we open a newspaper or turn on cable news there is evidence to confirm Mark Twain’s aphorism that “there is no distinctly native criminal class except Congress.”6

In 2008, for example, Rick Renzi (R-AZ) was charged with thirty-five counts of violating federal law. He had sold real estate to a business associate and then introduced legislation to increase its value dramatically by making it the subject of a federal land swap. He also diverted insurance premium money into his campaign treasury. Reporters then suspected Renzi of working the Bush Justice Department to have the US district attorney investigating his case fired. In 2005, Rep. Randy “Duke” Cunningham (R-CA) resigned after admitting to receiving gifts from the head of a defense company in return for his efforts to secure tens of millions of dollars in government contracts. The next March he was sentenced to over eight years in prison. The Cunningham story unfolded at the same time a number of Republican House members were caught up in a scandal involving the brash and influential lobbyist Jack Abramoff. Rep. Bob Ney (R-OH) resigned in 2006 and was later sentenced to thirty months for granting Abramoff, his associates, and often unwitting clients favors such as introducing legislation, inserting statements into the Congressional Record, and generating government business. In return Ney received such luxuries as foreign trips and the use of boxes at sporting events. Rep. John Doolittle (R-CA) resigned in 2009 after it was discovered his wife and chief of staff had been on Abramoff’s payroll and the congressman had received gifts and campaign contributions from the lobbyist. Doolittle personally promoted the interests of the lobbyist’s biggest clients, the Northern Mariana Islands and several Indian tribes. Five congressional staffers were directly connected to Abramoff’s schemes and pled guilty to charges.7

FIGURE 1.1 Gallup’s mean annual Congressional job approval scores, 1974–2011

Democrats have peddled influence for personal gain just as assiduously. In 2002 Rep. James Traficant (D-OH) became the first member expelled from the House in more than twenty years after he was convicted on ten counts of bribery, tax evasion, and racketeering for taking campaign funds for personal use. He served seven years in prison. Sen. Roland Burris (D-IL) was suspected of striking a deal with Gov. Rod Blagojevich (D-IL) so that he could be named to the seat vacated by Barack Obama when he left for the White House. Blagojevich was sentenced to fourteen years and Rep. Jesse L. Jackson, Jr., (D-IL) was caught up in the scandal. In 2011 the former chair of the Ways and Means Committee Rep. Charlie Rangel (D-NY) was tried and then convicted and censured by the full House for tax evasion, inappropriate use of member privileges, and wrongful leasing of property. Rep. William Jefferson (D-LA) received gifts for himself and family members in exchange for assisting a company in its dealings in Africa and the United States. Several aides were indicted, and Jefferson was stripped of committee membership by fellow Democrats after he was re-elected in 2006. He then went on to lose his very safe Democratic district in 2008 and was later sentenced to thirteen years in prison. The episode is perhaps best known for the discovery of $90,000 in the congressman’s freezer and a controversial FBI search of his congressional office.

The biggest fish to be found guilty of political corruption in recent years, however, was former House majority leader Tom DeLay (R-TX). DeLay was first elected to the House from the Houston suburbs in 1984 and quickly rose through the Republican ranks. He was Speaker Newt Gingrich’s (R-GA) whip immediately after the party captured control of the House for the first time in forty years in the 1994 elections. Known as the Hammer for his aggressive tactics and fierce partisanship—he co-led the K Street Project, an effort to pressure interest groups into hiring only Republicans—DeLay orchestrated Rep. Dennis Hastert’s (R-IL) rise to the Speakership after Gingrich resigned in 1998. In 2003, after his predecessor Rep. Dick Armey (R-TX) retired, DeLay took his seat as the number two member of the House.

DeLay was accused of numerous abuses. He was closely connected to Jack Abramoff, having been on an infamous golfing trip to Scotland with the lobbyist. Indeed, DeLay’s deputy chief of staff Tony Rudy left to work with Abramoff at his company Greenberg Traurig. A chief of staff, Ed Buckham, remains under investigation for close links with Abramoff. But it was for his fundraising in Texas state legislative races that DeLay was convicted. In an ultimately successful effort to secure a Republican majority in Austin willing to conduct a controversial and unscheduled congressional redistricting, DeLay directed corporate cash through his PAC to seven candidates for state legislature so as to hide the funds’ source. He was found guilty of felony money laundering by a state court in November 2010.

Of course, there have been sex scandals as well. Rep. Mark Foley (R-FL) resigned from Congress just before the 2006 elections after it was discovered he had sent sexually suggestive electronic messages to teenage male pages. House Republican leaders were roundly criticized for being unresponsive to earlier warnings about Foley’s conduct. Sen. Larry Craig (R-ID) was arrested for lewd conduct in a Minneapolis airport men’s restroom in the summer of 2007. Sen. David Vitter’s (R-LA) phone number was discovered during part of the investigation into “DC Madam” Deborah Jeane Palfrey’s escort service. Vitter quickly came out and admitted marital infidelity and a connection with the operation. He stayed in the Senate. Palfrey was convicted and later killed herself. Rep. Vito Fossella (R-NY) declined to run for re-election in 2008 after it became public knowledge that he had fathered a child with a woman who was not his wife. Fossella’s problems were compounded by a DUI arrest at the time the affair hit the news. Rep. Eric Massa (D-NY) resigned in March 2010 after a House investigation of claims that he groped male staff was revealed. Sen. John Ensign (R-NV) resigned in 2011 following press reports that his parents paid money to a former top aide whose wife had had an affair with the senator. The Senate’s ethics committee later found substantial evidence Ensign had violated federal law. Rep. Christopher Lee (R-NY) resigned suddenly in February 2011 after it was discovered he had essentially solicited sex on Craigslist. In May, Rep. Anthony Weiner (D-NY) used the Internet to send a lewd photo of himself to an unsuspecting Seattle woman. It was later revealed he had used social networks to make advances to women on a regular basis. When a porn star claimed she had received inappropriate messages from him, Weiner could no longer deflect the concerted push for his resignation within the Democratic Party, and he stepped down. Then in July Rep. David Wu (D-OR), who, according to staff, had been behaving erratically for some months, was accused of an aggressive and unwanted sexual encounter with a teenage girl. When added to previous allegations about sexual misconduct from his college days, the charge effectively forced the congressman’s resignation.

These episodes have merely built upon a foundation of disillusionment dug largely by scandals since the 1960s. It was then that Congress first aggressively and systematically investigated and prosecuted ethics violations—both bodies created select committees on standards of official conduct in the wake of incidents involving Bobby Baker, Sen. Lyndon B. Johnson’s (D-TX) chief of staff from his days as majority leader, and Rep. Adam Clayton Powell (D-NY). Four scandals were particularly harmful, largely because they involved so many members. The Koreagate investigation of the mid-1970s centered upon the South Korean government’s efforts to prevent a US military withdrawal from its peninsula. Through a businessman called Tongsun Park, the South Koreans channeled bribes and favors to as many as ten Democratic House members, of whom three were censured or reprimanded and one was convicted and sentenced to prison. In the Abscam scandal of the late 1970s and early 1980s, the FBI used a fictional sheikh to offer money in return for political favors. Six lawmakers were convicted of bribery. Five senators were investigated for their improper efforts to protect Charles Keating’s savings and loan from federal investigators in the late 1980s, of whom one, Alan Cranston (D-CA), was rebuked formally by the Senate’s ethics committee. In the early 1990s a series of investigations into the operations of the House Bank and Post Office discovered many members had overdrawn their accounts for a prolonged period and others had laundered money using postage stamps and postal vouchers. Four former members were convicted or pled guilty on charges related to the banking scandal, two, including Rep. Dan Rostenkowski (D-IL), the chair of the Ways and Means Committee, went to prison for their roles in the post office affair. In fact the 1976–1990 period was particularly bad for Congress. For these and other indiscretions, a total of four House members were censured and seven formally reprimanded. Two senators—Herman Talmadge (D-GA) in 1979 and David Durenberger (R-MN) in 1990—were censured.

Scandal even surrounded two House Speakers at the end of the twentieth century. Rep. Jim Wright (D-TX) resigned in 1989 after the House’s ethics committee issued a report criticizing his acceptance of honoraria and royalties for a book he had written as well as efforts to use his official position to secure a job for his wife.8 In 1997 Newt Gingrich was fined $300,000 by the body’s ethics committee for misleading its investigation into possible misuse of funds generated by a college course the speaker taught.9

It is certainly true that Congress has attempted to clean up its act. When the Republicans took power in 1995, both bodies increased registration requirements for lobbyists. They also instituted a gift ban that prohibited privately paid recreational travel and greatly reduced the value of meals and presents members and their staff could receive from official representatives of organized interests. When the Democrats vaulted into House and Senate majorities after the 2006 elections, they secured passage of the Honest Leadership and Open Government Act. The legislation restricted the ability of departing members to lobby their former colleagues, placed significant limits on the kind of travel members could undertake, and established a comprehensive ban on gifts. In 2008, the House established the Office of Congressional Ethics—a body made up of outsiders granted the authority to initiate investigations against members suspected of unethical behavior. All this had little effect on Americans’ views of legislators’ integrity, however. According to an April 2011 Rasmussen poll, 43 percent of respondents believed most members of Congress were corrupt. A Gallup November 2009 poll revealed 55 percent of Americans believed members of Congress had “low” or “very low” “honesty and ethical standards.” This was the highest level of distrust reported for lawmakers since Gallup began the survey in the late 1970s—greater than that of both stockbrokers and car salespeople.10

Self-Obsession

Many Americans have a theory about this behavior. Senators and representatives are believed to be, in the famous words of political scientist David Mayhew (1974a), “single-minded seekers of reelection.” Everything they do is interpreted by the press and public alike as a way of enhancing their chances of being returned to Washington—whether to accumulate further power or feather their own nests. This would not be so bad if it came with an energetic commitment to constituent needs and the broader public interest. But the citizenry has a seemingly unshakeable belief that members are intensely self-interested and care little for anyone or anything but themselves and their own political careers. A June 2010 Gallup poll revealed that, among those who felt most members did not deserve to be re-elected that fall, about a third came to their opinion because they saw legislators as self-absorbed and unconcerned with the everyday problems Americans faced. The other two-thirds split on their reasons—many cited members were doing a bad job, focusing on the wrong issues, or had just been in Congress too long.11

Intensive efforts to secure re-election and a fundamental negle...