This is a test

- 258 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

This book, offering reader the opportunity to reflect on ideas in the field of systemic and family therapy, examines the cross-fertilization of ideas that can result from an integration of systemic theory, personal construct theory, and the influential work on the analysis of narratives.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Interacting Stories by Rudi Dallos in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Psychology & History & Theory in Psychology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER ONE

Cybernetics and family therapy

"We presume that the universe is really existing and that man is gradually coming to understand it. By taking this position we attempt to make clear from the outset that it is a real world we shall be talking about, not a world composed solely of the flittering shadows of people's thoughts ... people's thoughts also really exist, though the correspondence between what people really think exists and what does really exist is a continually changing one."

George Kelly, 1963, p. 6

Theories, like children in families, sometimes turn out to be clearly visible continuations of their parents and at other times to appear radically different or even contrary. Systems theory is no exception. At its inception, psychoanalytic thinking was the dominant force in psychotherapy, and subsequent systems theorists both connected to these ideas and also adopted positions that became increasingly more opposed to it. My intention in this chapter is to consider both what appear to me to have emerged as some of the dominant concepts within a systems theory framework and also what aspects seem to have been relatively ignored or subjugated. This also captures the fundamental approach of this book, which is the idea that there are, inevitably, different versions or stories available of events in families, as there are of theoretical frameworks. So, systems theory does not exist in any definitive sense but lives as different versions in our personal interpretations—the varied ways that each of us connects with these ideas. Whilst supporting this personal view, it may also be fair to suggest that, over time, some versions of a theory become more accepted, more dominant, than others and coalesce together to form a version that starts to take on the status of being the "real" or "correct" version.

This process may be necessary to help us to organize and clarify important aspects and differences between theories, but it may also blinker us and even lead us to reject ideas that are useful. There is some danger that this is happening with system theory. One influence of the powerful emergence of constructivist and social constructionist ideas appears to be a rejection of systems theory, in some cases almost wholesale. This may be unfortunate and a case of "throwing the baby out with the bath water" or what Jacoby (1975) referred to as a "social amnesia" —a consumerism of ideas: "Within psychology new theories and therapies replace old ones at an accelerating rate ... the application of planned obsolescence to thought" (p. xxviii).

This is not to argue that theories should not be criticized and rejected in part or whole when necessary, but that we should be careful that the grounds on which we reject a theory are valid rather than fuelled by fashion and shining newness. An amusing example of such processes can be seen in currently popular critiques of psychoanalytic theory—e.g. that Freud was simply a product of his time, and that even his "genius" could not rise above his cultural conditioning. But, as early as 1914, Freud wrote:

We have all heard the interesting attempt to explain psychoanalysis as a product of the peculiar character of Vienna as a city ... that neuroses are traceable to disturbances in the sexual life, could only have come to birth in a town like Vienna. ... Now honestly I am no local patriot; but this theory about psychoanalysis always seems to me quite exceptionally stupid. [Freud, 1914, p. 325]

He also stated dryly: "... First they call me a genius and then they proceed to reject all my views" (p. 142; Wortis, 1974). To realize that he was aware of such possible criticisms (early in his career) and to read what he thought of them perhaps prompts us to think a little further. Likewise, with systems theory it is fashionable to offer sweeping criticisms—e.g. that early theorists paid little attention to emotions, families' beliefs, the meanings they gave to events and societal factors—yet a reading of the early literature shows this to be eminently untrue. At the same time, I cannot claim to offer any definitive account of what some of the influential thinkers in the systemic movement did think. It is fashionable—or postmodernist—to say that there can only be competing narratives or stories, and so my interpretation of systems theory is no more valid than any other—just my own view. This is, of course, partly true, but at the same time there may be some versions (mine included) that ignore, distort, or have never encountered some important aspects: "All ideas are not equally true, and hence not all are equally tolerable. To tolerate them all is to degrade each one" (Jacoby, 1975, p. xviii).

More practically, I frequently meet academics and practitioners who explain that they have some knowledge and experience of family therapy but now do not find much use for systems theory. They often go on to say things about it such as:

- It is pathologizing and normative, in making assumptions about "healthy" families. In so doing, it also simply moves the level of blame or attribution of responsibility from individuals to the family, so that families are the new scapegoats. Hence, its claims to be a radically new way of looking at problems is a bit of a sham.

- Likewise, that it accepts the "nuclear", conventional family model as the norm ignores the rich diversity of modern family life and casts blame on alternative forms, such as single-parent families or families from diverse cultures.

- That it is mechanistic and deterministic in viewing people as parts of interacting systems, like a central-heating system. It ignores people's potential for autonomy, choice, and taking control of their own lives.

- It is cold and non-emotional in having little to say about the complex feelings, joys, sorrows, anguish, and satisfactions that are a fundamental part of relationships.

- In contrast to point (1), systems theory is seen, in its claim to be neutral and to view all problems as arising from interactions, implicitly to condone abuse and oppression in families—e.g. in cases of abuse or violence, sometimes one or more members of a family are to blame and should be held responsible for their actions.

Apart from a touch of sadness, one of my responses has been to defend systems theory by saying something along the lines of, "Ah, well, it's changed quite a bit, they don't assume that any more ...". But, in fact, it never was like this for me. These were not the stories or narratives that I heard when I first came across systems theory, first in a theoretical context and, five years later, in a therapeutic one. In both it appeared as an elegant, ecological, realistic, and intelligent theory, contrary to the above criticisms, which presented a different version or interpretation to mine. Within the systemic movement, there are also debates, and some appear likewise to be so different from my view that it is almost as if we are talking about a different theory altogether. At first, I thought that it was simply my misunderstanding of some fundamental shifts in thinking that had taken place. But then I started to realize that I was not alone. Many therapists and researchers still felt that aspects of systems theory are useful and should not so readily be discarded. What follows in the remainder of this chapter is an attempt to outline some of what I see as the core ideas that underpin systems theory. In addition, I offer some reflections on these ideas—-in particular, observations about some of the subjugated aspects of these ideas, aspects that offer some important connections with current thinking but have been forgotten, neglected, or relegated out of our consciousness. These reflections are presented in italics.

Systems Theory and Feedback

From the 1950s onwards, a number of theorists (Ashby, 1956; Bateson, 1972; von Bertalanffy, 1962) developed ideas that came to be known as the field of cybernetics. Some of the impetus for these ideas came from the biological sciences, where it was observed that an analysis of an organism, such as the human body, into its component parts and specific functions could not adequately explain the ability to maintain stability and form in the face of varying demands for change. It was suggested that the body could be seen as a set of components that operated together in an integrated and coordinated way to maintain stability. The coordination was seen to be achieved through communication between the components or parts of the system. Bateson (1958) was one of the first to suggest that a variety of social relationships—rituals, ceremonies, family life—could be seen as patterns of interactions developed and maintained through the process of feedback:

Feedback is a method of controlling a system by re-inserting into it the results of its past performance. If these results are merely used as numerical data for the criticism of the system and its regulation, we have the simple feedback of the control engineers. If, however, the information which proceeds backwards from the performance is able to change the general method and pattern of performance, we have a process which may be called learning. [Wiener, 1954, p. 84]

This became a key concept in family therapy—namely, that some information about the effects or consequences of actions returns to alter subsequent action. Rather than focusing on how one event or action causes another, it was suggested that it is more appropriate to think of people as mutually generating jointly constructed patterns of actions based on continual processes of change.

Jackson (1957) went on to propose that a symptom in one or more of the family members develops as a response to the actions of the others in the family and becomes in some way part of the patterning of the system. Attempts to change the symptom or other parts of the system were seen to encounter "resistance", since the system operated as an integrated whole. By "resistance", Jackson implied not a conscious but a largely unconscious pattern of emotional responses to change in one or other family member: "A husband urged his wife into psychotherapy because of her frigidity. After several months of therapy she felt less sexually inhibited, whereupon the husband became impotent" (Jackson, 1957, p. 88). In social interaction, the functioning of groups of people made up a pattern, a meaningful whole that was greater than the sum of its individual parts. By analogy, family dynamics are like a piece of music or a melody that we hear as the combination of the notes, but each individual note gains its meaning in the context of the others—the total gestalt or whole. The concept of homeostasis was employed to describe the tendencies of systems to preserve a balance or stability in its functioning in the face of changing circumstances and demands. A system was seen to display homeostasis when it appeared to be organized in a rule-bound, predictable, and apparently stable manner. As an example, Hoffman cites a triadic family process:

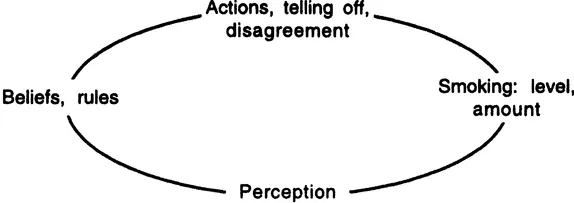

The triangle consists of an ineffectively domineering father, a mildly rebellious son and a mother, who sides with the son. Father keeps getting into an argument with son over smoking, which both mother and father say they disapprove of. However, mother will break into these escalating arguments to agree with son, after which father will back down. Eventually father does not even wait for her to come in; he backs down anyway. [Hoffman, 1976, pp. 503-504]

We can see here a pattern of actions, but how do we draw this as a system? One version might be to focus on the smoking as the trigger, which, when it is perceived, leads to the activation of a set of beliefs and rules leading to further actions (see Figure 1.1). However, potentially there are an infinite number of other ways we could describe this system: for example, focusing on father's level of dominance, or the level of collusion between mother and son, or even on the son as a system—his nicotine intake, arousal level, level of addiction, and so on. A system is not static but always in motion, ever changing. In the example above, arguably what we in fact are seeing as homeostasis is patterning over time. We can even call this a narrative or story about how these people interact over a period of time. However, during this period the system will look different at any given point: for example, the son does not always have a cigarette in his hand; at times they are not discussing his smoking but doing something totally different and unconnected to it, like going to work or making love; and so forth:

Figure 1.1. A simple cybernetic system

No behaviour, interaction, or system ... is ever constantly the same. Families, for example, are perpetual climates of change —each individual varies his behaviour in a whirlwind of interactional permutations ... a "homeostatic cycle" is a cycle that maintains constancy of relations among interactants through fluctuations of their behaviour. [Keeney, 1983, pp. 68 and 119]

Families do, of course, have explicit rules, such as the children's bedtimes, manners at the dinner table, and so on, but the more interesting rules were seen to be the implicit ones that we as therapists could infer, e.g. that when mother scolds her son, the father usually pretends to go along with it but subtly takes the boy's side. The smoking example can be seen to contain a covert rule that the mother will take the boy's side in family agreements even over issues where she actually agrees with the father. However, we could suggest various alternative rules depending on where we choose to look, e.g. that contact between the boy and his father is initiated through his smoking. In practice, what constitutes a system is always a construction, a belief, or an idea in the mind of the observer: "Cybernetic epistemology suggests that there are as many forms of cybernetic systems as there are of drawing distinctions" (Keeney, 1983). Which view we adopt is partly a question of choice and usefulness. However, some versions may certainly appear to make more obvious sense than others.

Critics of early systems theory formulations argued (Dell, 1982; Keeney, 1983) that Jackson's model of families displaying pathology as operating like closed homeostatic systems promoted a vision of families as mechanical (not even biological) systems, with little awareness, insight, or capacity for change or evolution. Yet Jackson (1957) had suggested that family homeostasis should be seen as the operation of a set of propositions about rules governing their interactions, He emphasized that these rules should be regarded as if: "the rule is an inference, an abstraction ... a metaphor coined by the observer to cover the redundancy he observes" (Jackson, 1957, p. 11). In other words, they existed in our minds as observers, not "really" in the families "out there". Jackson also made clear in his writings that he regarded people in relationships as capable of voluntary and deliberate action. It is interesting to realize that a view of a system as a hypothetical abstraction that was more or less useful was fundamental to systems theory.

Communication, Emotions, and Symptoms

Keertey (1983) points out that the early pioneers of cybernetics approaches were aware that a system was not simply composed of components that engaged in behaviours. The fundamental aspect of a system was that the parts were in communication with each other. Most importantly, communication between the parts of a system—the members of a family—was not necessarily, or even predominantly, conscious. By analogy to biological systems, communication can occur through electrical impulses, chemical secretions, and so on. In human systems, communication can occur at a variety of levels, such as gestures, proximity, voice tone, posture, breathing rate, smell, touch, and so on. Watzlawick, Beavin, and Jackson (1967) had suggested that any action can potentially count as a communication and, further, that any communication is multi-faceted, so when we speak we are also emitting a variety of non-verbal messages.

What is predominantly communicated non-verbally is emotion—how people feel in relation to each other, how they feel about what has just been said or done. Emotional processes were absolutely central in Jackson's (1957) original formulations of families as homeostatic systems:

The paternal uncle of a woman patient had lived with her parents until she was 10 when he married. Her mother's hatred of him was partially overt; however, his presence seemed to deflect some of her mother's hostility toward her husband away from the husband, and the brother gave moral support to the father. Following this uncle's departure, four events occurred that seemed hardly coincidental: The parents began openly quarrelling, the mother made a potentially serious suicide attempt, the father took a travelling job, and the patient quietly broke out in a rash of phobias. [Jackson, 1957, p. 82]

The "constancies" proposed to be operating in families were seen to be related to deep-seated, often unconscious fears associated with changes in the satisfactions of needs and dependencies. F...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- EDITORS' FOREWORD

- FOREWORD by Arlene Vetere

- Introduction

- CHAPTER ONE Cybernetics and family therapy

- CHAPTER TWO The roots of constructivist systemic therapy: nothing convinces like success

- CHAPTER THREE Beliefs, accounts, and narratives

- CHAPTER FOUR Choosing narratives and interacting

- CHAPTER FIVE Dominant narratives— social constructionist perspectives

- CHAPTER SIX Narratives, distortions, and myths

- CHAPTER SEVEN Evolving and dissolving problems: a co-constructionist approach

- REFERENCES

- INDEX