eBook - ePub

Intellectual Property in Chemistry

A Guide to Applying for and Obtaining a Patent for Graduate Students and Postdoctoral Scholars

This is a test

- 127 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Intellectual Property in Chemistry

A Guide to Applying for and Obtaining a Patent for Graduate Students and Postdoctoral Scholars

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

This book provides detailed instructions for reading and writing a patent. The book presents useful instructions for undergraduate and graduate students as well as post-doctoral, researchers and professors in the field of Chemistry and related areas. Written from a practical point of view it answers the simple and often asked question: how should I read and write a patent? The book is particularly directed to graduate students, who are initiating their research and often lack experience with patents. The ability to write and comprehend patents is fundamental for the success of their projects.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Intellectual Property in Chemistry by Nelson Durán,Leandro Carneiro Fonseca,Amedea B. Seabra in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Bildung & Forschung im Bildungswesen. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

chapter one

Introduction

1.1 General aspects

The intellectual property right (IPR) law defines intellectual creations entitled to protection, how to obtain (or lose) IPR, how to use and benefit from IPR, and how to enforce IPR and obtain compensation for infringements. All of these aspects are important to understand well to avoid infringing other people’s IPR.

Very recently, an important seminar of Royal Society of Chemistry Law Group, named “Introduction to Intellectual Property for Researchers” was presented on May 2016 in London. This document provided an introduction to IPR for researchers in chemistry. The document was ideal for any researcher with a primary or no knowledge of patent and other IPRs. This type of seminar is extremely important for the comprehension of this area in which all are interested, namely, university, industry, and any civil member of our community.

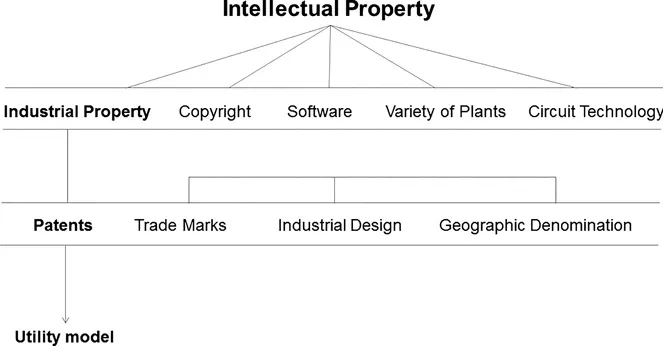

The intellectual property (IP) involves several groups, such as industrial property, copyright, software, variety of plants or plant breed, and circuit technology, as shown in Figure 1.1.

Figure 1.1 Modalities of intellectual property rights.

The copyright includes the following:

- Copyright which covers (a) artistic, literary, and scientific works; (b) computer programs; and (c) scientific discoveries.

- Related rights shall cover the interpretations and performances of performers, phonograms, and broadcasts.

Software: Although in the Brazilian IP computer programs are protected by copyright, these are analyzed by a specific legislation (Law No. 9.609, February 19, 1998) known as Software Law (www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/Leis/L9609.htm, accessed March 5, 2017).

However, the IP protection related to computer software has been deeply discussed at various levels. In the European Union (EU), a Directive on the Patentability of Computer-implemented Inventions has also been debated for harmonizing the rendering of the national patentability demands for this kind of computer software-related inventions, including the business procedures carried out via the computer. The debate showed devious views among stakeholders in Europe. Besides, the Internet augmented complex issues concerning the performance of patents, as patent protection is fixed on a country-by-country basis, and the patent law only pays off within its own countries (www.wipo.int/sme/en/documents/software_patents_fulltext.html, accessed March 5, 2017).

Industrial property covers the following:

- Patents which protect inventions in all the areas of human activity;

- Trademarks and business names;

- Industrial designs and models;

- Geographical indications.

Plant variety covers the following: Cultivated, traditionally bred, medicinal and aromatic plants can also be protected by a different way of plant breeder’s rights. In many cases, the countries offer special legal protection for the products of plant breeding applying the International Convention for the Protection of New Varieties of Plants (van Overwalle, 2006).

Topographies of integrated circuit covers the following: Integrated circuits (ICs), named also as “chips” or “micro-chips,” are the electronic circuits where all the components, such as transistors, resistors, and diodes, have been mounted in a rigid order on the surface of a semiconductor material.

In the actual technology, ICs are important elements for a wide range of electrical tools or products, such as watches, TVs, home tools, cars, smart phones, and computers, among other digital devices. The innovative layout design of ICs is the basic for the manufacture of any smaller digital devices with different properties or functions. Albeit creating a new layout is normally the result of a huge investment, either in financial terms or in terms of the time required by highly qualified experts, reproducing such a scheme or layout design may cost only a fraction of the initial investment. With the view to avoid nonauthorized copying of this kind of designs and to provide incentives for applying investment in this area, the layout design, which is in this case topography of ICs, is protected by a sui generis IP system (www.wipo.int/patents/en/topics/integrated_circuits.html).

Since this book will be devoted to patent, the patent definition and the concepts involved with it will be explained in detail.

1.1.1 Patents

A patent is an official document issued by the government that describes an invention and furnishes an adequate right to exclude other parties from utilizing the invention for commercial objectives. This right is granted by a national government, upon application and pursuance, in exchange for the entire disclosure of an invention. The disclosure is first a confidential disclosure to the Patent Office which, in Brazil, Canada, and currently in the United States, becomes a nonconfidential disclosure to the public 18 months later. This kind of patent grants to the applicant exclusivity and rights to use or sell the information claimed in the invention for a short period of time. It is worth to observe the distinction between inventor and owner: an inventor obtains the patent issued in his or her name; however, an inventor always will be an inventor. The inventor may then assign the property of the invention to someone else. In many countries, patents have a lifetime of 20 years from the date of early filing and payment of the prescribed annual fees, of 17–20 years depending on the different countries (CAGS, 2015).

We have to keep in mind that a patent is not a discovery but an invention. To be acceptable for a patent, an invention is necessary to fulfill the following three main criteria: (a) must be novel or new, (b) must have some utility such as functional and/or operative, and (c) must not be obvious to a person skilled in the area of the invention.

Then, it is clear that a patent is granted for the physical embodiment of an idea or also applied to a process that produces something marketable or real, in other words, commercially negotiable. Products, processes, manufactures, or novel and useful compositions of matter, as well as not only any new and useful upgrading of these elements but also new uses of a known compound, are subjected to be a patentable matter.

Nonpatentable issues include ideas, scientific principle, theorems, or some invention that is illegal or involving illicit purposes. Natural phenomena and laws of nature are not eligible for patent protection.

Another possibility for IP right to protect inventions is the utility model. This right is at hand in many national statutes. It is closely to the patent but usually has a shorter term (often 6–15 years) and less rigorous patentability requirements. The utility models can be depicted as second-class patents (www.wipo.int/sme/en/ip_business/utility_models/where.htm, accessed March 6, 2017).

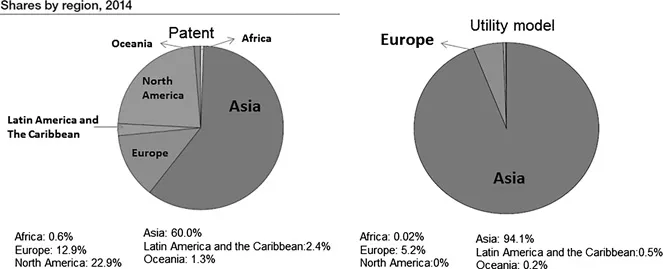

The terms of patents and utility models are represented in Figure 1.2.

IP offices in Asia registered the highest number of applications for patents and utility models. Specifically, a combined share of 60% of all patent applications worldwide came from Asian offices. These data contrast to the shares received by offices in North America (22.9%), Europe (12.9%), and Latin America and Caribbean (2.4%). In the case of utility models, Asia office was more significant (94.1%) than Europe (5.2%), North America (0.0%), and Latin America and Caribbean (0.5%).

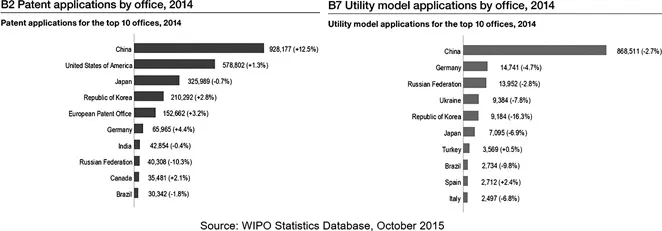

In 2014, China reported the highest number of patent applications received by any single IP office, maintaining this position since 2011. China received more applications than Japan along with the United States. Middle-income countries, such as Brazil and India, rank among the top 10 despite having received fewer applications in 2014 compared to 2013. From the top 10 Intellectual Priority offices, China’s IP office (+12.5%) saw the highest annual growth in filings received in 2014. On contrary, the office of the Russian Federation had a decline of 10.3% (Figure 1.3).

The IP office of China followed the same profile with the largest number of utility model applications in 2014, considering for just over nine tenths of the world total. The offices of Germany (14,741) and the Russian Federation (13,952) obtained similar numbers of applications, as close to the Republic of Korea and Ukraine with about 9,200 and 9,400, respectively. Recently, China saw a decrease in the number of applications filed at its office (Figure 1.3; http://www.wipo.int/edocs/pubdocs/en/wipo_pub_943_2015.pdf, 2016, accessed March 6, 2017; World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO), 2016).

Figure 1.2 Pie charts present, for each intellectual property right, the distribution of intellectual property-filing activity across the world’s six geographical regions. (Source: WIPO (Word Intellectual Property Organization), reproduced with modification.)

Figure 1.3 Patent and utility model applications by office in the top 10 offices in 2014. (Source: World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO), reproduced under permission of Creative Commons—Attribution (BY) 3.0 IGO—license.)

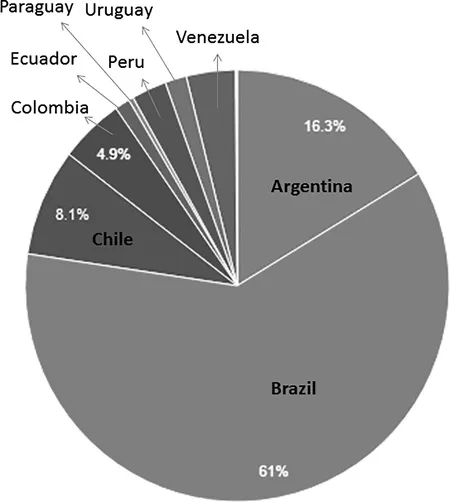

In Latin America, Brazil (61.0%), Argentina (16.3%), and Chile (8.1%) appear to be the most productive in patent during 1980–2015 (Figure 1.4).

Similar statistics were recently published by the Brazilian government (Instituto Nacional da Propriedade Industrial (INPI); www.inpi.gov.br/sobre/estatisticas; Jorge et al., 2017).

1.2 Patenting process through years

The first historical reference to an institution responsible for issuing and archiving patents was at 1679, with the creation of the General Board of Trade and Currency (GBTC) of Spain. This GBTC of Spain had the responsibility to increase economic growth. Invention rights in Spain were granted before 1679 by the King of Spain in the 15th and 16th centuries.

The first establishment of patent laws in the United States was in 1790, and the patent numbering started in 1836. During the International Exhibition of Inventions in Vienna (1873), foreign exhibitors refused to participate in this exhibition, because they were afraid that someone else would steal and commercially use all their ideas in different countries. From this confusing situation appear the needs to create a system to protect the IP. Ten years later (1883), the Paris Convention for the Protection of Industrial Property was created. This was the first international treaty created to help the people to have protection of their invention in a particulate country in other country for their ideas and intellectual creation under the industrial property rights (IPR).

Figure 1.4 WIPO intellectual property in Latin America (Patent 1980–2015). (Source: WIPO (Word Intellectual Property Organization).)

The U.S. Constitution gives to the Congress the power to decree laws relating to patents. Then, the Congress has decreed laws relating to patents until now. Important than in 1980, the Bayh–Dole Act gave universities title to the property of inventions resulting from research support by the federal government, since before that time, title ownership belonged to the government. In 1984, the Hatch–Waxman Act was approved. This act permitted generic drugs to enter the market. After 1984, the generic drug company was required only to demonstrate bio-equivalency of the generic drug. In 1886, the Berne Convention for the Protection of Literary and Artistic Works appears and in 1988 the European Union legislation, United Kingdom: Copyright, Designs and Patents Act. In Brazil, in 1996, the Law No. 9.279 of the Industrial Property Law was approved by the Brazilian government.

The American Inventors Protection Act (AIPA) of 1999 brought changes in the U.S. patent...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- Authors

- Chapter 1 Introduction

- Chapter 2 Patent profile

- Chapter 3 How to use databases in patent search

- Chapter 4 Practical exercises in patent search

- Chapter 5 Use of advanced patent search

- Chapter 6 Practical exercises by the advanced patent search

- Chapter 7 How to read a patent

- Chapter 8 How to write a patent: Basic information

- Chapter 9 Final conclusions and perspectives

- References

- Index