- 336 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Issues in Geography Teaching

About this book

Issues in Geography Teaching examines a wide range of issues which are of interest to those teaching geography from the early years through to higher education, including:

- the role of research and the use of ICT in teacher training;

- the significance of developing critical thinking skills;

- broader educational issues such as citizenship and development;

- the importance of environmental education;

- the position and role of assessment;

- the present state and status of geographical education and issues that are likely to be of concern in the future.

Issues in Geography Teaching details the contexts, presents the facts and raises thought-provoking questions which should stimulate further interest and discussion.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

1 School geography 5–16

Issues for debate

Introduction

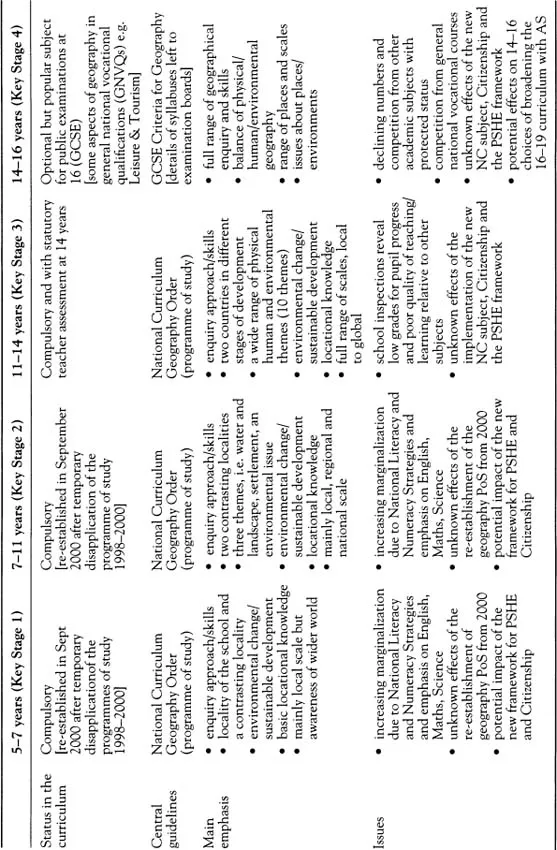

With the National Curriculum Review 1998–2000 now completed and the revised, less prescriptive programmes of study for geography ready for implementation in September 2000 (DfEE, 1999), it is timely to examine the state of the subject for pupils aged 5–16. Geography has now been re-established in Key Stages 1–3 (after the temporary disapplication of its Key Stages 1–2 programmes of study 1998–2000), so it is now a full part of the statutory ten-subject National Curriculum for pupils aged 5–14 years. Despite the traumas of the past ten years of curriculum change, gains have been made for geography, as a direct result of the National Curriculum (Rawling, 1999). Geography is also a popular optional subject with high entries for public examinations at 16-plus (GCSE) and 18-plus (A-level), and new one-year Advanced Subsidiary Levels are about to provide further possibilities for geography in the 16–19 curriculum. There are now central guidelines for the subject at all these levels (National Curriculum Order, GCSE and A/AS-level Criteria), containing considerable detail about the subject content to be taught in physical, human and environmental aspects of the subject and about the standards expected (see summary diagram, Table 1.1 for the 5–16 situation). There is then a framework as a basis for development into the next century.

However, despite this apparent strength, there are a number of concerns about the future status and quality of geographical education in England. It will be argued that school geography has lost status since the initial establishment of the National Curriculum (1988), is in danger of losing curriculum ground to so-called ‘basic’ skills and the new National Curriculum subject of Citizenship, and provides considerably less evidence of creative flair and curriculum innovation than was the case pre-National Curriculum. Many of these trends are a direct result of central policies designed to improve the school curriculum, so it may be salutary to consider the unintended impacts on one particular National Curriculum subject.

Four issues concerning the status and well-being of school geography in England will be considered. In each case, an attempt will be made to draw out wider implications and a concluding section will summarize the possibilities for action. The issues are:

Table 1.1 School geography 5–16: A summary for 2000

• geography and the threat of the ‘basics’;

• geography and ‘preparation for adult life’;

• the decline of school-based curriculum development;

• school geography as part of a wider geography education system.

Geography and the threat of the basics

In 1997, nine years after the introduction of a National Curriculum designed to raise standards, the incoming Labour Government found continuing concern about basic literacy and numeracy in English schools. National Curriculum test results for English and Mathematics (used as measures of literacy and numeracy) seemed to show that large numbers of primary school children were still not reaching the required levels of achievement in these subjects. Media attention given to this situation and to some international comparisons (Martin et al., 1997) fuelled concern and it was not surprising that the new government decided to make literacy and numeracy its own priorities. The first White Paper of the new government (DfEE, 1997a) was an educational one which stridently claimed that ‘the priority for the curriculum must be to give more emphasis to literacy and numeracy in primary education’. As a direct result, government educational policy has focused on the twin track of setting demanding targets for schools to achieve by 2002, and on initiating prescriptive national teaching strategies for both literacy and numeracy. The targets state that by 2002, 80 per cent of 11-year-olds should reach National Curriculum level 4 in English and 75 per cent of 11-year-olds should reach level 4 in Mathematics (DfEE, 1997b). The National Literacy Strategy (DfEE, 1998) is being implemented in schools from September 1998 and the National Numeracy Strategy (DfEE, 1999) follows suit from September 1999.

Though the intention to address perceived shortcomings in these important basic skills is generally welcomed, the consequent impact on the wider curriculum is giving more cause for concern. In January 1998, the government announced that it intended to release schools from the National Curriculum requirements in ‘the non-core six’ – i.e. History, Geography, Design and Technology, IT, Art and PE – so that schools could give more time to literacy and numeracy. Although this was publicized as being a temporary two-year measure, the recent (1998–2000) review of the National Curriculum subjects has been focused on reducing content in precisely these non-core six subjects (QCA and DfEE, 1999) so that, although the subjects will be reinstated, it is unlikely that the full statutory breadth and balance of the National Curriculum will return in 2000. What is more, the National Curriculum subject Orders for English and Mathematics have now been brought directly in line with the Literacy and Numeracy strategies. Effectively, the broad and balanced National Curriculum of 1988 has now been replaced by a much narrower vision and one which elevates one particular definition of the basics and apparently downgrades other subject contributions.

For geography, just beginning in 1998 to show the benefit of ten years of recognition in the National Curriculum in improved teaching and learning in geography for 5–11-year-olds (OFSTED, 1998a), this change of emphasis is of great concern. Despite QCA guidance on the need to maintain a broad curriculum (QCA, 1998), many schools have, not surprisingly, decided to delay full implementation of the Geography Order. Even in those where geography was flourishing, local education authority advisers have reported a decrease in time dedicated to the subject and a narrowing of emphases. Creative ideas about geography’s many contributions to literacy and numeracy, published in Primary Geographer (e.g. two full issues, January and July 1998) and elsewhere (e.g. Development Education Association leaflet, 1998) have been valuable, but it has proved difficult to encourage schools to diverge from the tightly prescribed guidelines for the government-approved literacy and numeracy hours. Recent informal surveys undertaken by LEA advisers show that geography has been a particular casualty of this new policy, even though what limited evidence there is about the primary curriculum seems to suggest that, contrary to the government’s thinking, schools which retain a broad and balanced curriculum actually perform better in National Curriculum English, Maths and Science tests (OFSTED and DfEE, 1997).

In April 1999, it was announced that the National Literacy Strategy was to be extended to Key Stage 3. Although the plans and guidance for this Key Stage are still being developed and, certainly, Key Stage schemes of work for non-core subjects will include reference to language and literacy, the main emphasis is likely to remain on the English curriculum. At Key Stage 4, there are already signs that a narrower view of the curriculum holds dangers for geography. The broad ten-subject National Curriculum for 14–16-year-olds was already amended in 1994, after schools found it impossible to cover the detailed requirements set out in the first versions of the subject Orders. The notion of a hierarchy of subjects was introduced by Sir Ron Dearing at that time, with the core subjects of English, Mathematics and Science occupying a central position and, more controversially, some element of Design and Technology, Information Technology and Modern Foreign Languages also being protected. Geography became an optional subject, in competition for curriculum time with other National Curriculum subjects (e.g. History, Art), non-National Curriculum subjects (e.g. Business Studies) and the newly developed general vocational courses. The inevitable decline in numbers of pupils opting for GCSE geography is taking place with 4 per cent, 8.5 per cent and 3.1 per cent reductions in candidates being registered in 1997, 1998 and 1999 respectively. History numbers have seen a similar decline and Bell (1998), in a paper to the British Educational Research Association, noted that constrained option choice for 14–16-year-olds has also resulted in a substantial decline in numbers taking both history and geography (22 per cent, 1984; 11 per cent, 1997).

As Marsden points out for primary geography (Marsden, 1998), important wider issues are raised by these situations. It is not merely a question of ‘heads down and fighting our corner’ for geography in an increasingly competitive situation. It is crucial that geographers, along with other subject specialists, challenge the assumption that learning in the basics or the core subjects is somehow opposed to and independent of learning in other subject areas. Geography can undoubtedly be an effective and motivating medium for learning basic as well as subject-specific skills, as the recent Schemes of Work for primary geography make clear (DfEE and QCA, 1998). Matthew Arnold’s observations on the deadening effect of the basic ‘Revised Code’ primary curriculum in England reveals that he felt that this was true in the late 1880s as well:

I find in them [schools] in general, a deadness, a slackness and a discouragement, which are not the signs and accompaniments of progress. Meanwhile … geography and history, by which, in general, instruction first gets hold of a child’s mind and becomes stimulating to him, have in the great majority of schools fallen into disuse and neglect.

(Arnold, 1910)

In addition, it can be argued that at all Key Stages there are other basic entitlements which should find a place in any curriculum. Indeed, the original National Curriculum seemed to recognize this by its breadth of subjects, although the overloaded requirements made it impossible to deliver. Perhaps, as geographers, we should be asking ourselves ‘What is the minimum entitlement in our subject which is essential for every future citizen?’ How important are, for example, basic map skills, some locational knowledge, environmental awareness and understanding of global interdependence for the twenty-first century and how clearly linked are these by the general public with the school subject, geography? A flurry of articles in the press, in early May preceding the 1999 National Curriculum consultation, seemed to show that the public image (or at least the media’s image!) of geography is still one of a predominantly factual subject, with little recognition of its contribution to understanding major environmental, social and political issues. It is interesting to note that the science community in England has also been undertaking such a rethinking exercise about entitlement to Science (Nuffield Foundation, 1998) and some of this seems to have borne fruit since the Secretary of State’s letter introducing the National Curriculum consultation (May 1999) has recognized that ‘keeping National Curriculum Science in step with the changing world of the 21st century’ is a major issue still to be addressed. Can geographers make the same case? Initial signs from the review of the National Curriculum are not promising. The primary curriculum is likely to remain in the grip of narrowly defined literacy and numeracy, with other subjects reduced to brief lists of required content. The Key Stage 3 curriculum will not escape the pressures of literacy and numeracy. Although some interesting ideas were considered for Key Stage 4 during the Review (e.g. about a curriculum based on entitlement to broad areas of experience with schools free to plan the detail), the government intends to maintain the existing view of ‘core and others’, leaving more adventurous changes for the longer term (QCA and DfEE, 1999). Unless we can make and justify a convincing case for a geographic entitlement for all (possibly using the new requirements for Citizenship and Personal, Social and Health Education as one lever), geography’s future in England may be as a minor extra to the primary curriculum ‘if time permits’, and a marginal academic offering for some 14–16-year-olds.

Geography and ‘Preparation for Adult Life’

Preparation for Adult Life (PAL) is the term coined in England to refer to the ‘new agenda’ of the Labour Government, covering personal, social and health education, citizenship, education for sustainable development and the spiritual, moral, social and cultural dimensions. In reviewing the National Curriculum for the year 2000, Ministers have wished to ‘create space’ for these aspects of education, alongside the existing ten-subject National Curriculum, already perceived as overloaded by many schools (SCAA, 1997a).

Since 1988, geography has suffered in England from this continuing tension between the desire to prescribe detailed subject content to be taught for individual National Curriculum subjects and the need to recognize, and leave room for, some of the wider purposes of schools in preparing pupils for adulthood. The Education Reform Act of 1988 stated that every pupil should be entitled to a curriculum which was balanced, broadly based and ‘prepares (such) pupils for the opportunities, responsibilities and experiences of adult life’ (DES, 1989a: 7). The guidance booklet produced by the Department of Education and Science (1989b) explained that the National Curriculum, as specified, was not intended to be the whole curriculum – ‘they [the foundation subjects] are necessary but not sufficient. – More will however, be needed to secure the kind of curriculum required by Section 1 of ERA.’ The booklet identified a whole range of areas which schools would need to address, including targeted activities such as careers education and guidance, broader dimensions such as multicultural education, and cross-curricular themes like political understanding. Such matters were taken very seriously by the government’s advisory body (then the National Curriculum Council) which, during 1989 and 1990, developed a full set of Curriculum Guidance booklets to help schools teach five cross-curricular themes. Ministers, however, saw this as distracting attention from the main task of implementing the National Curriculum subjects and, after a major disagreement between the NCC’s Chief Executive, Duncan Graham, and the Secretary of State for Education (described in detail in Graham, 1993), the status of the booklets was downgraded and schools were left in no doubt that the National Curriculum subject content was the main priority.

The problem has remained throughout the 1990s. Whatever the Act states about preparation for adult life, a highly detailed and subject-based National Curriculum has left schools little room for manoeuvre in curriculum planning. With no clear statement of aims and priorities for the education of each age group, schools have assumed that the ten National Curriculum subjects (and particularly the core subjects wi...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- List of figures

- List of tables

- Notes on contributors

- Introduction to the series

- Introduction

- 1 School geography 5–16: issues for debate

- PART I Issues in training geography teachers

- PART II Issues in the geography classroom

- PART III Wider issues in teaching geography

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Issues in Geography Teaching by Chris Fisher, Tony Binns, Chris Fisher,Tony Binns in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Education & Counseling in Career Development. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.