![]()

1

Guide to the book

Technology assessment (TA) has its origin in the United States Congress more than 50 years ago. Since then, it has developed into a worldwide movement, considerably diversified according to different expectations and new challenges. Fueled and orientated by theory-based approaches, TA has been disseminated in various fields of practice and across different thematic fields. This book provides a comprehensive overview of technology assessment through an account of its practices, as well as a theoretical view of TA, in order to identify its conceptual specificity. The introductory chapter presents the overall orientation of the book’s ideas, together with an overview of the content.

1.1 Motivation and objectives

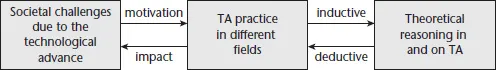

TA is, according to its history, neither a scientific discipline nor a field of mere practice. Rather, as will be demonstrated in this book, its very core consists of a specific relationship between practice and theory which expresses itself in the technology assessment process. By intention, the familiar order of talking about theory and practice (e.g., Habermas 1963) is reversed throughout this book. In technology assessment, practice to meet societal challenges comes first, historically as well as systematically (Decker/Fleischer 2010). TA practice is diverse and comprises different elements such as parliamentary TA, TA involved in public debates, and TA as part of extended engineering processes. The task of theory is to identify commonalities among these different practices and to open up spaces for learning, for systematizing TA’s knowledge, and for further development. The story of TA to be unfolded in this book thus may be characterized by a simple figure (Figure 1.1).

This figure should be read starting from the left, following the arrows to the right and then returning to the left. It represents the idea that TA has been developed to meet societal challenges in the context of scientific and technological advances. The issues of unintended side effects, of the ambivalence of technology and the need for technology development in accordance with the Leitbild1 of sustainable development, illustrate these challenges well. They belong to a larger set of different motivations for TA (Chapter 2) which guided the emergence and development of different types of practice Chapter 3). The interplay between societal challenges and TA practice is made subject to theoretical reasoning in two respects: considering its specific assessment process (Chapter 4) and exploring the role of TA in its social constellations (Chapter 5). After having performed both steps of theorizing, I will reconsider TA’s practice and draw conclusions in several respects, in particular on its methodology (Chapter 6). The discussion of TA will conclude by presenting some general reflections and perspectives (Chapter 7).

Figure 1.1 Technology assessment: motivation, practice, and theory

The overarching goal of this book is to give comprehensive insight into TA at the level of both practice and theory. Four objectives inform this goal:

- (1) The basic assumption and point of departure for writing this book is that TA has developed a conceptual identity beyond the diversity of its motivating challenges and responding TA practices. Observations in favor of this assumption are that an engaged and ongoing TA debate has now been conducted for decades; that TA networks have been founded and have flourished; and that workshops and conferences have been organized. In fora, on platforms, and in media such as conferences and workshops, TA practitioners together with some theoretically interested scholars have met across all the diversity of TA practice. This seems to be an indication that there is indeed some conceptual identity within TA. The first objective of this book is to investigate and uncover this presumed identity of technology assessment and make it explicit.

- (2) The second and more practical objective is related to the observation that there is still no comprehensive monograph on technology assessment available at the international level. Many papers and project reports deal with TA; some papers focus on specific aspects of it (e.g., Cruz-Castro/Sanz-Menendez 2005, Guston/Sarewitz 2002), and a few edited volumes have been published around technology assessment (e.g., Grin et al. 1997, Vig/Paschen 1999, Decker 2001, Decker/Ladikas 2004, Rip et al. 1995, Scherz et al. 2015, Klüver et al. 2016). However, there is no overview available to present TA to different audiences such as graduate students, lecturers and professors, researchers entering the field of TA, scholars from neighboring fields, policy-makers, or TA practitioners. Thus, the main practical objective of this book is to fill this gap as a contribution to TA’s capacity-building, teaching, and further development.

- (3) The third motivation responds to the observation that TA has consisted primarily of different practices, ranging from parliamentary technology assessment, through public engagement, to TA involved in engineering processes. Though there has been a lively theoretical TA debate, again and again there has been evidence of a gap between theory (often related to the fields of science, technology, and society (STS) studies, ethics, or philosophy) and practice, where, for instance, relationships with commissioners and customers of technology assessments such as members of parliament carry more weight than theoretical reasoning. The value of theory for TA’s practice is not seen at all by some of its practitioners, while theorists sometimes suspect TA’s practice of being blind to overarching issues and ignorant of theoretical considerations. The third objective of this book is therefore to overcome this unhelpful constellation and to bring the practice and theory of technology assessment into a fruitful relationship, assuming that this will enable mutual benefits.

- (4) The fourth objective is related to the presumption that technology assessment might be more than a highly specialized endeavor at the interface of technology and society. Rather, it could be a specific manifestation of a larger paradigm shift in the relations between science, technology, politics, and society at large. In this case, the emergence of TA and its development over the last 50 years would be an indicator of larger changes and transformations. This issue, however, goes beyond the scope of TA itself and will be discussed only briefly (Sect. 5.1.2, Sect. 7.3).

1.2 Preliminary understanding of TA

Neither a clear and uncontested understanding of technology assessment nor a substantial definition accepted throughout the TA community is yet available. The properties and constitutive elements of TA, and also its boundaries, are not really transparent; at least, they are not fully explicit. This sometimes leads to specific ambiguities in TA journals or at TA workshops and conferences. When papers are submitted, the question repeatedly comes up in the review process: is this really a paper on technology assessment, or is it beyond its scope? This diversity also makes criticism of TA difficult because there is no consensus as to what TA is.2 At first glance, it might therefore appear surprising that TA could have emerged and developed over decades without a clear definiens guiding decisions on such inclusion and exclusion.

However, it might be more fruitful to regard this issue the other way around. The lack of definition and clarity has allowed scholars, researchers, and practitioners, as well as funding agencies and political institutions, to play around with the notion of technology assessment and related approaches (Sect. 3.5), to explore new approaches, and to experiment with new methods and formats. The vagueness of the notion, when interpreted as openness, has perhaps been a strength for creative exploration of the field over the past few decades.

Nevertheless, even if this presumption applies, it would not necessarily be a helpful starting point for the analysis in this book. At the beginning of any scientific book, the object to be explored must be clearly characterized, and the scope of the investigation has to be made transparent. Consequently, it is necessary to say something about the assumed meaning of technology assessment in this introductory chapter. The task of this section is therefore to provide the reader with a preliminary understanding and to prepare the ground for identifying the TA practices to be presented later (Chapter 3).

As indicated in the title of this book, the practice of TA comes before theory (Figure 1.1). Technology assessment did not show up by itself, nor was it initiated by the sciences and humanities according to theoretical considerations or top-down reasoning. Rather, it was invented and introduced in the political system in the 1960s in order to meet contemporary challenges at the interface between technology and society. TA’s development over the past decades has been strongly guided by requirements and expectations emerging from different fields of practice in society. TA’s orientation to societal challenges is reflected in the structure of this book. Chapter 2 is dedicated not to technology assessment itself but rather to the societal constellations forming its motivational background; the motivations presented in that chapter still build the horizon of what TA is expected to deliver.

The horizon of challenges and motivations, however, does not allow us to derive a clear definition of TA which could be used to categorize specific activities as technology assessment and to exclude others.3 The reason for this is that the challenges TA responds to are much too broad and too big. Some of them even coincide with the so-called grand challenges (Sect. 3.2.3).4 There is a huge area of activities designed to meet those challenges, of which TA covers only a small and specific part. For example, the climate change issue is a typical unintended consequence of the use of modern technology, e.g., of coal power plants and diesel engines (Sect. 2.2.3). Many activities are undertaken worldwide to combat climate change or to slow it down, e.g., by introducing more energy-efficient technologies of heating and shifting energy supply to renewable sources. There is some TA in this field (e.g., GAO 2010, cf. Sect. 3.2.3), but most of the activities consist of political and economic interventions, e.g., subsidies for renewable sources of energy, regulating greenhouse gas emissions from automobiles, or promoting the development of more efficient technology by funding research and development (R&D). Thus, there is a need to clarify the specific nature of technology assessment more precisely amongst other activities intended to meet the same challenges.

A preliminary understanding of technology assessment to orientate the presentation of TA’s practices (Chapter 3) must consist of a heuristic which allows selected practices to be subsumed under the umbrella of TA while leaving others beyond it. The following four considerations will serve as a heuristic orientation in this sense.

First, the practices explicitly named “technology assessment”, or characterized by related terms such as technology evaluation or technology foresight (Sect. 3.5), will be taken into consideration. This approach does not replace a definition but serves as a first step in opening up a space to convene practical experiences and cases which can then be used for further clarification. It presupposes that the term “technology assessment” has not been used in a completely arbitrary way in various practices. This presupposition is supported by the fact that there has been a conceptual and methodological debate on TA since the 1970s which is documented in a considerable corpus of literature (e.g., Ayres et al. 1970, Hetman 1973, Wynne 1975, Paschen et al. 1978, Rip et al. 1995, Schot/Rip 1997, Joss/Bellucci 2002, Grunwald 2009, Klüver et al. 2016). This debate provides a frame of reference for technology assessment and made the emergence of a TA community possible. Hence, we do not need to start from scratch but can rather build on some evidence grounded in that debate.

The second issue distinguishes technology assessment from pure academic reasoning. Meeting the challenges at the interface between technology and society and serving the expectations with which TA is confronted implies that technology assessment aims at creating impact and making a difference. This can apply to policy-making, public debate, or engineering. Impact created by TA may be a contribution to transformation, a piece of policy advice orientating a political debate, or raising public awareness, amongst other dimensions:

Impact of TA is defined as any change with regard to the state of knowledge, opinions held or actions taken by relevant actors in the process of societal debate on technological issues.

(Decker/Ladikas 2004, 61)

The third criterion separates TA from strategic intelligence in the economy. Two different aspects of technology-based innovation, products, services, and systems have to be distinguished: (1) aspects affecting the common good as a whole, e.g., issues of observing citizen’s rights or maintaining a sound national economy, are obliged to political reasoning and democratic decision-making, with environmental norms and safety regulations as examples, and (2) aspects which may be delegated to economic competition, market developments, and individual consumers’ preferences. The relation between developments left to the marketplace and those regarded as subject to political regulation may differ in individual cases and may be contested between representatives with different understandings of the relation between the state and the economy. According to its history and self-understanding, TA addresses those technology aspects which are of public interest and therefore should be made subject to political reasoning and democratic decision-making. There are some relations here with strategic thinking in the economy, e.g., with respect to the use of foresight methods, but the crucial difference is between TA’s obligation to transparency, inclusion, and democratic debate, on the one side, and the necessity for private and exclusive knowledge in the highly competitive economy, on the other. In recent years, these traditional boundaries have become more permeable in some respects. The growing significance of sustainability reporting and corporate social responsibility of companies has emphasized their role as actors in society beyond their mere economic position. Industry and other actors in the economy are currently also addressed by the RRI movement (e.g., Iatridis/Schroeder 2016). This field, however, would need its own consideration and is beyond the scope of this book, which will focus on TA in the public sphere.

Fourth, there is an opportunity to cross-check the above-mentioned criteria against former descriptions of TA. Besides approach (1), it is possible to build on earlier attempts to characterize TA beyond its particular practices. The following characterization was developed in the project TAMI (Technology Assessment – Methods and Impacts) (Decker/Ladikas 2004), funded by the European Commission:

TA is a scientific, interactive, and communicative process which aims to contribute to the formation of public and political opinion on societal aspects of science and technology.

(Decker/Ladikas 2004, 14)

This pragmatic definition was commonly approved by the partnering institutions joining the TAMI project. They represented a large variety of TA practices, which adds considerable value to this definition. However, this approval was achieved at the price of being not very specific. Another characterization of TA was developed by Guston/Sarewitz (2002), focusing more on its aca...