![]()

One

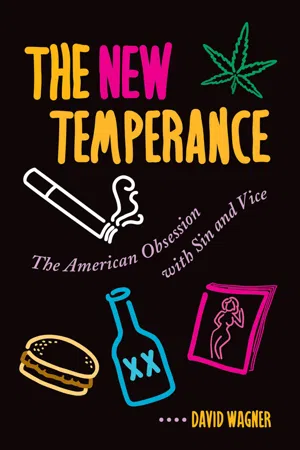

The New Temperance

The last decades of the twentieth century may well be remembered as a time when personal behavior and character flaws dominated the American mind. As prominent political figures from Gary Hart to Robert Pack-wood were brought down by personal scandals, even death seemed to provide no respite from examination of behavior and morality The media reported on the deaths of the Grateful Dead’s Jerry Garcia and baseball star Mickey Mantle as exercises in moral diagnosis. Mantle was said to have died from too much “partying”; and Garcia, from assorted drugs, cigarettes, and food. Constant public service announcements, political speeches, and public health pronouncements urge us to “just say no” to drugs, cigarette smoking, fatty foods, teen sexuality, non-monogamous sex, and violent TV shows and music lyrics. Typically, the media have applauded such changes as reflecting the new mood of the times:

New Age on Campus: Can the Keg

Campus social life no longer revolves around the keg party…. “The whole culture is more wellness-conscious. Certainly our students are. The promotional stuff does sink in after a while about what alcohol does to your body,” said Earl Smith, dean of Colby College. “We’ve got a fearful generation that’s come of age now between AIDS, dating violence and the much more serious repercussions of driving drunk,” said Mike O’Neil, coordinator of a Vanderbilt University program that shelled out $60,000 this year to students who agree to run nonalcoholic parties.1

New social problems, from eating disorders to “codependency,” were discovered in the 1970s and 1980s, while older unmentionable problems such as child abuse and domestic violence continued to draw public attention. The 1990s, meanwhile, are witnessing the emergence of still newer problems of the personal:

Is a Waft of Fragrance Poisoning Your Space?

“It’s sort of like cigarette smoking,” she [Schmidt] complains. “They are invading my privacy” Whether she realizes it or not, Schmidt is part of what could be the next big nationwide battle that pits individual rights against public health concerns: the push for fragrance-free environments.

Support Group Helps People with “Messy” Problems

A walk through Judy’s house used to mean stepping over piles—piles of magazines, piles of catalogues, piles of letters…. So Judy started a chapter of a support group—“Messies Anonymous” for slobs. … After the group was written up in the Miami Herald, “I got 12,000 letters saying, ‘Help!’” Felton said.2

The Coercive Consensus

Although the New Temperance is in part a matter of national mood, and of a turning inward since the 1960s away from broader social and political concerns, the focus on personal behavior is not only a matter of style. The new mood in America also reflects a coercive strategy of punishment for those who fail to conform to the new norms.

Beginning in the 1980s, no amount of control, however personal or onerous, was considered excessive to stamp out the ingesting of drugs. By the 1990s, the “war on drugs” was leading to more than 1 million arrests a year, the majority of them for possession of small amounts of illicit substances. The drug war—complete with mandatory drug testing in many workplaces, mandatory criminal sentencing, and constant surveillance, particularly in ghetto areas—has been the major factor responsible for filling American prisons to record numbers. The drug war almost ensures that African-American males driving in poor neighborhoods will be stopped and searched3 and, in some areas, that white, middle-class high school students will have their lockers and possessions searched. Mothers have been arrested, charged with ingesting drugs into their fetuses; medically ill people have been denied access to drugs for medicinal purposes; and even religious rituals such as the American Indian use of peyote have been halted—all because of the war on drugs.

The drug war now includes among its targets legal drugs such as alcohol and tobacco. The charge of hypocrisy by public health and liberal critics of the drug war has spawned an almost equally virulent war against these substances. As a result of recent legislation, many people with alcoholism or drug addiction are being cut from the Social Security disability rolls as a punitive measure. Youths unlucky enough to be caught with alcohol at a sports event or behind the school building incur charges tantamount to treason, leading at times to suspension or expulsion from school. In many New England towns, police are ticketing and even arresting youthful cigarette smokers. And some companies and public employers are refusing to hire cigarette smokers, whether their smoking is on or off the job.

Yet such repression never seems quite enough, as new calls for surveillance and punishment continue to appear. Consider this recent report from my local paper:

Plan Enlists Community in Drug War

Police would conduct searches of school lockers at a moment’s notice. Store owners would routinely call police when they suspect a customer of buying alcohol for minors. Residents whose homes are used for teen parties with drugs and alcohol would be warned of the legal consequences. Clergymen would speak about substance abuse during church services. Those deterrents were part of a Community Wide Substance Abuse Policy being proposed.4

Rivaling the alarm over substances is the panic over sex and sexual displays. Beginning with the rise of the New Right in the 1970s, wars have been waged against promiscuity, pornography, and teen pregnancy. Democrats soon joined Republican enthusiasts in promoting “family values” and condemning out-of-wedlock births and teen sex.5 A key ingredient of conservative attacks on welfare benefits has been the pathologization of the single mother and teen parents. But not to be outdone, President Clinton fired his first Surgeon General for talking about masturbation, while his secretary of Health and Human Services called out-of-wedlock births “morally just wrong.”6 By the 1990s, the consensus against sexuality had reached the point where politicians were competing with one another to support measures to control movies and TV; approving “v-chips” for parents to control children’s television, advocating censorship on the Internet, and pressuring advertisers (such as Calvin Klein) to withdraw sexy ads.

Conservatives are sometimes outperformed by putative liberals on the New Temperance issues. Washington Mayor Marion Barry, a Democrat, only recently released from prison for his conviction for crack use, has called for mandatory Norplant implants for young women who are sexually active.7 And liberal columnist Ellen Goodman has suggested that government fight the war against teen pregnancy by tracking down older male teens who are having sex with younger teens: “A substantial number of the men are what can only be called sexual predators. A substantial number of teen-age mothers are what we once called jailbait. … Maybe statutory rape is an idea whose time should return.”8

The line between health warnings and moral suasion, on the one hand, and force, on the other, is a thin one. Even the new food moral-ism—touting the avoidance of fat or meat, promoting correct eating—sometimes turns into social control. For instance, my local “alternative” paper recently featured an article about a welfare recipient who was followed around and charged with (among other things) spending her money on “junk food.”9 Conservatives who criticize any pleasurable use of taxpayer money are joined by liberals who disapprove of such dietary excess: In a letter to the same paper, a person complained that “a meat market is soon to move into… [name of] Street. What kind of message will this send to the neighborhood, including the kids across the street at [name of] School?”10

The present book explores how the America of “sex, drugs, and rock ’n’ roll” of the 1960s and early 1970s became so consumed with personal behavior and social control by the 1980s and 1990s. Elements of the Left as well as the Right now vie with each other to stamp out drugs, nonmarital sex, and unhealthy habits, differing only, it seems, on the question of which groups to punish more.11 As politicians no longer rail against communism but emphasize their toughness on crime, drugs, sexual abuse, and violence in the media, this book asks “Why?” What some have called the “new sobriety,” others have termed the “new puritanism,” and still others have praised as the new health consciousness or “healthism,” I will define here as the “New Temperance.”12

Defining the “New Temperance”

For most Americans and certainly the majority of the educated public, a large percentage of daily human behavior has become pathologized in the last two decades. Whether the topic is cigarette smoking or fatty foods, teen pregnancy or excessive television viewing, we have been constantly bombarded with messages about health and morality. My intent is not to argue that any or all of these behaviors are healthy or wise, nor do I advocate that the reader smoke cigarettes, drink alcohol to excess, take illegal drugs, or engage in violent behavior. Of course, health messages contain some friendly advice.

But to acknowledge risks, is, from a sociological perspective, not to explain very much about the American obsession with personal behavior. This book argues the constant focus on personal behavior in America serves as a tool of political power as well as a popular social movement. Temperance is a national ideology. That is, Americans of the last two decades seem to have become rigidly focused on problems of personal behavior, as if such issues explain all of life and provide meaning to all events. To say something is an ideology is not to argue that all of its observations and ramifications are negative or undesirable. Temperance ideology has much basis in real life; indeed, life has many risks and dangers, and it is good to be warned of them. But ideologies are highly culturally and politically contextual. What one culture sees as risky, others would not. Many Indian tribes saw tobacco as a god, whereas for some Americans today it evokes only concerns about secondary smoke and death. The members of most indigenous cultures are shocked upon first observing Westerners driving around in huge steel boxes that frequently crash (and always spew off smoke). They regard cars as bizarre and quite dangerous. Even in the industrialized world, though, temperance is an especially American ideology.13 For example, when I visited Hungary, I couldn’t explain to my hosts why many Americans would be surprised at their high-fat diet, their heavy smoking, and the easy availability of drink and pornography at virtually each corner. I found similar opinions in Sweden, where people laughed at these American obsessions, along with our new taste for decaffeinated coffee and our dismay over teen sexuality. Nor is temperance only a matter of national or cultural boundaries. America has not always been consumed by temperance ideologies, as anyone who grew up in the 1950s, 1960s, or 1970s can affirm.

America has long witnessed moralistic popular movements against citizens’ sins and vices (see Chapter 2). Because the most famous was the Temperance Movement, lasting from the 1820s to the passage of National Prohibition (against alcoholic beverages) in 1919, I draw upon this name. Although I mean to define temperance as being far more than a movement against alcohol, there are persuasive reasons to recall this earlier movement. First, as we shall see, although American temperance activists saved their sharpest denunciations for the “demon rum,” temperance organizations and activists in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries had close links with many long-forgotten movements including the Vice and Vigilance Movement and the Social Purity Movement, which campaigned against prostitution, promiscuity, pornography, and “white slavery”; the Anti-Cigarette Movement; the Social Hygiene Movement aimed at preventing venereal diseases; and a variety of popular health movements stressing proper diet, sexual rectitude, and proper exercise, such as that typified by cereal inventor Dr. Harvey Kellogg (whose popular health movement joined water cures, vegetarianism, and exercise with temperance and sexual chastity).14

Second, it makes sense to discuss today’s behavioral control movements in terms of temperance because, like the old (anti-alcohol) Temperance Movement, they produce similar political alignments. As in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, rural fundamentalists and conservative traditionalists have become allied with urban middle-class “progressives,” uniting some elements of the Right and Left.15 Such movements focus not on broad economic, social structural, or cultural failings of American society but, rather, on individual behavior (though liberal temperance activists criticize a few sectors of corporate power such as the liquor and tobacco industries). And as with the Temperance Movement of old, today’s universalist claims about the harms of “immoral” behavior hide major subtexts of anxieties about social class, race, and ethnicity. Temperance activists of the past saw rum as corrupting immigrants and other poor people, whereas today the ghetto “underclass” is the locus of American fears. The writers of old temperance tracts warned their middle-class readers against the evils of whisky, whereas today’s middle class seems to have an almost bottomless pit of anxiety, focusing on everything from street crime to secondary smoke to teen and child sexuality. Although I would not reduce all of these anxieties solely to economic causes, Barbara Ehrenreich’s imputation of a “fear of falling” in the American middle class, leading this class to constantly examine behavior as status cues, does explain some of the paradoxes of middle-class angst.16 For example, how do we reconcile the rising middle-class fear of drugs and cigarettes with evidence of sharp declines in these behaviors over the past many years? One possible answer is that temperance ideology helps distinguish the anxious “respectable classes” from grungy “lowlifes” who may still smoke cigarettes or marijuana, much less use crack cocaine, and that such boundary markers have salience only when the middle class is able to differentiate itself from other classes based on behavioral norms.

My approach differs somewhat from other sociological treatments of these concerns (see Chapter 3). I understand temperance to be an ideology, but also an elite strategy, on the one hand, and a popular social movement, on the other. Most social science treatments stress only one part of the equation. For example, some social scientists—especially proponents of the “medicalization of social problems” thesis—tend to focus exclusively on professionals and related experts as shapers of social problem definitions. Others stress only the media’s influence or the popular appeal (“moral panics”) of certain problem formulations. These are certainly aspects of the New Temperance, but they don’t completely explain it. Accordingly, the present book builds on social constructionist theory while also integrating this approach with other theories. The work of French philosopher and social critic Michel Foucault is particularly helpful toward this end, as his understanding of power strategies and their diffusion throughout society helps us to comprehend how elites develop strategies that are then used by a variety of other forces in society and how power mechanisms may originate at the bottom but become useful for elites.17

With this introduction, I can now define today’s temperance ideology, movement, and strategy as reflecting a belief in the responsibility of the state and private powers (e.g., corporations) to regulate and restrain personal behavior. Although public health and public education workers hope to instill successful individual efforts at self-control, the failures of self-regulation justify society’s more coercive role for the presumed “own good” of the individual. Of course, activists involved in one aspect of behavioral concern do not always support suppression of other behaviors. Nevertheless, the New Temperance can generally be seen as focusing on the following four areas:

- Substance Abuse: I refer here to the movements to villainize and repress or punish drug users. These m...