![]()

PART I

Introduction to comparative rural policy studies

![]()

1

WHAT IS RURAL? WHAT IS RURAL POLICY? WHAT IS RURAL DEVELOPMENT POLICY?

Ray D. Bollman and Bill Reimer

Introduction

There has been a long-running conversation on the meaning of rural and rurality. Often, observers develop a profile or typology for rural residents, rural enterprises, or rural institutions and then use these characteristics to define rural or rurality. Alternatively, the focus may be on geographical localities (either spaces or places), with the typology developed from the distribution of residents, enterprises, or institutions within and across those localities.

The objective of this chapter is to review this discussion in order to clarify the spatial dimensions that define rurality versus the characteristics of individuals (or enterprises or institutions) along the rural–urban continuum.

Rurality is a spatial concept. The two key dimensions of rurality are the density and distance-to-density of the localities of actors (individuals, enterprises, or institutions). In other words, the dimensions of density and distance-to-density define the rurality of the geographical localities of actors. Many characteristics of rural actors are correlated with rurality. However, these characteristics do not define rurality.

The meaning of rural policy follows directly from the two dimensions of rurality for localities. Specifically, considering the implications of the two rurality dimensions for any given policy would constitute “rural” policy. For example, considering density and distance-to-density implications of development policy would constitute the “rural” in rural development policy. This attention to rurality has been instituted as “rural proofing” or a “rural lens” in a number of jurisdictions.

There are various ways to delineate the grid or the spatial boundaries of geographical localities and to measure their density and distance-to-density. This chapter reviews the considerations required to implement these measures. The exact choice of measures will depend upon the analytic objective being pursued.

The preparation of statistical tabulations and the desire to target public policy requires the determination of the spatial grid (i.e. the boundaries of each locality) and the thresholds for density and for distance-to-density in order to classify localities or regions. These thresholds do not define “rurality”. The choice of the threshold simply classifies actors associated with the localities at given points along the continuum of density and distance-to-density

For many purposes, analysts should consider the broader regional milieu within which each community is located. Similarly, for an analysis of regions, analysts should consider the mix of rural versus urban communities that comprise each given region.

These perspectives are discussed in the context of historical and current debates on the interpretations of rurality. Discussion questions are offered regarding the nature of the operational trade-offs needed to implement a measure of rurality for any given investigation.

Since the empirical implementation of a measure of each dimension of rurality ultimately depends on the issue(s) being considered, it is critical that analysists are skilled at understanding and evaluating the appropriate way to measure each of the conceptual dimensions when addressing a given issue.

What is rural?

Theory vs operational variables

Before discussing the theoretical idea of rurality versus the empirical measures of rurality, it is important to distinguish between a theoretical construct and an empirical variable that attempts to measure the theoretical construct. One should start with the theoretical concept and then search for ways to measure (or operationalize) that concept.

A theoretical construct (Box 1.1) may be considered to be an abstract feature of a phenomenon or process. Typically, these constructs are not directly measurable.

Box 1.1

A theoretical construct is a relatively abstract construct (or concept) that describes the essential features of a phenomenon. These constructs are (typically) not directly observable.

Operational definitions identify measurable variables that attempt to capture the essence (often partially) of the theoretical concept. This involves two steps:

1 identifying which empirical measure(s) most closely capture(s) the theoretical construct; and

2 identifying which procedure or data collection methodology will be used to generate the empirical measure.

Correlates are variables (usually empirical) which vary together. There may or may not be causal processes driving the correlations.

Once the theoretical constructs are identified, analysts need to search for empirical measures (or variables) that can best represent the concepts. This process involves two decisions: first, one must assess the appropriateness of alternative empirical variables and chose the one(s) that most closely capture(s) the essence of the theoretical construct; and second, one must consider the procedure or the methodology that represents the best way to obtain the empirical measure

Two or more variables may be correlated. In other words, they are interconnected at an empirical level. However, correlation does not mean causality. Specifically, a correlation between two variables may not indicate a causal relationship (i.e. if one sees more of “x”, then one will see more of “y”).

More importantly, these correlated variables should not (or more assertively, must not) be used to define the theoretical concept.

The theoretical concept of rurality

Rural is a spatial concept (Reimer and Bollman, 2009; World Bank, 2009). Whether it is used for statistical, analytical, personal, or polemical objectives, “rural” implies something about the geographical location of its object. Even where “rural” is used in a metaphorical sense, it implies actors in localities with low density and/or a long(er) distance to higher-density localities.

Theoretically speaking, rurality refers to geographical localities with respect to two theoretical dimensions:

• their density; and

• their distance-to-density.

Frequently, density may be indicated by the population size of a locality and distance-to-density may be indicated as the physical distance or the money and/or time expended to travel to a locality of high(er) density. A detailed discussion of measurement issues is provided below.

Thus, localities that are more “rural” are those with a relatively low(er) population or institutional density and/or with a relatively long(er) distance to high(er)-density localities. Urban localities are those with a relatively high(er) density. Variations on these generalizations create a large number of possible propositions regarding the impacts of density and distance-to-density on opportunities and behavior as suggested below.

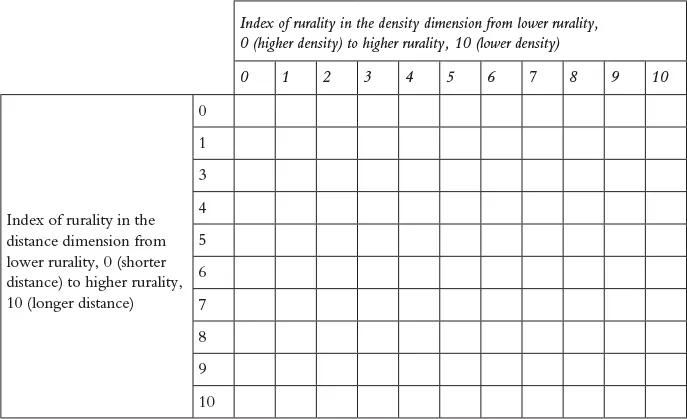

The relationship between density and distance to high(er)-density localities is most usefully represented as a continuum – as illustrated in Table 1.1. Individuals residing in a locality in the upper-right-hand part of this diagram are residing in a smaller town (i.e. higher rurality in the density dimension) that is adjacent to an urban or metro center (i.e. lower rurality in the distance-to-density dimension). Metro-adjacent individuals have easier access to urban or metro jobs and services (e.g. hospitals1) and a market to sell their goods and services. At the same time, they are living in a small-town locality (i.e. higher rurality in the density dimension). These individuals likely experience a small-town “way-of-living” (perhaps less air pollution, less crime, fewer traffic jams, etc.) but are able to access a metro market and metro services. Individuals residing in a locality in the lower-left-hand part of this diagram cannot (easily) access the market or services of an urban or metro center (i.e. high rurality in the distance dimension) but are residing in a larger town (i.e. lower rurality in the density dimension). These individuals are constrained to “small-town” or “small-city” opportunities (e.g. employment or services) but are living in a locality with a higher population density that would support the availability of many services, such as found in a regional service center.

Table 1.1 The two dimensions of the rurality of localities on a scale from 1 to 10

Operational definitions

The specification or choice of empirical measures of density and distance-to-density requires one to answer three questions.

1 What are the options for delineating the geographic boundaries or selecting the geographical units (i.e. a geographical grid such as community, county, region, etc.) that are most suitable to study the issue at hand?

2 What are the options for empirical measures of density and distance-to-density?

3 What are the options for establishing thresholds of the empirical measures for:

a the tabulation and publishing of statistical tables; and/or

b the designation of “rural” localities for targeting policies and programs.

The choice of geographical units for the empirical measures

The first operational choice required is the selection of the geographical unit (e.g. neighborhood, town, county, regional district) that best represents the “places” or “localities” appropriate for the issue being studied (du Plessis et al., 2001).2 For example, the choice of the spatial unit will depend upon whether one is studying an issue with a neighborhood focus (e.g. daycare), an issue administered at the county level, or an economic development issue to be considered for a functional economic area. This choice will, in turn, represent the “locality” in the grid in Table 1.1.

For many community-level issues requiring community-level data, there will also be a need to know the characteristics of the region within which the community is embedded. Similarly, for many regional-level issues, it may be important to know the characteristics or the mix of communities within the region. For example, what are the differences in family income among the communities in the region? Are all the communities in the region approximately the same size or is there a dominant community in the region? Also, how is the population distributed within the region?

If no data are available for the theoretically appropriate geographic grid, there will be a loss of information. For example, if community is the appropriate spatial grid but data are only available at the county level, then one is missing the variation among the communities in the county as the county-level data will only show the (population-weighted) average for all communities in the county. Using county-level data rather than community-level data will generate (perhaps very) different empirical relationships between rurality measures (density and distance-to-density) and the behavior or outcome that is the object of the analysis. In fact, one would expect (very) different estimates of the size of the empirical relationship between each of the independent factors and the behavior or outcome being analyzed when using county-level data compared to using community-level data.

Measuring density (as a continuous variable)

The choice of this measure will also be determined by the analytic question being considered. Typically, the population size of the locality would be an appropriate choice. In some cases, the population per square kilometer might be more appropriate. However, there may be specific investigations that would call for a density measure such as the density (number) of social networks (perhaps on a per capita basis) or the density (number) of individuals diagnosed with diabetes (again, perhaps on a per capita basis), as two examples. For analytical questions, generally, the chosen measure of density would be entered as a continuous variable in the empirical analysis. Data availability may also constrain the choice of the appropriate geographic grid for the empirical estimate of density.

Measuring distance-to-density3 (as a continuous variable)

The choice of the measure of distance-to-density would also be determined by the analytic question being measured. For example, the transportation of goods would likely require a different set of measures compared to the transfer of services (such as the transfer of accounting services or travel agent services by the internet).

The road distance might be suitable for many analytic questions. More likely, the time cost and/or the money cost of making the trip would be a more suitable measure. The question of distance to “where” w...