This is a test

- 444 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

Emile Male's book aids understanding of medieval art and medieval symbolism, and of the vision of the world which presided over the building of the French cathedrals. It looks at French religious art in the Middle Ages, its forms, and especially the Eastern sources of sculptural iconography used in the cathedrals of France. Fully illustrated with many footnotes it acts as a useful guide for the student of Western culture.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access The Gothic Image by Emile Male in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Art & Art General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Book IV

Chapter I

The Mirror of History. The old Testament

I.—The Old Testament regarded as a figure of the New Testament. Sources of the symbolic interpretation of the Bible. The Alexandrian Fathers. St. Hilary. St. Ambrose. St. Augustine. Mediæval Doctors. The Glossa Ordinaria. II.—Old Testament types in mediæval art. Types of Christ. Symbolic windows at Bourges, Chartres, Le Mans and Tours. III.—Old Testament types of the Virgin. The porch at Laon. Influence of Honorius of Autun. IV.—The Patriarchs and the Kings. Their symbolic function. V.—The Prophets. Attempts in mediæval art to give plastic form to the Prophecies. VI.—The Tree of Jesse. The Kings of Judah on the façade of Notre Dame at Paris, at Amiens, and at Chartres. VII.—Summary. The symbolic medallions in Suger’s windows at St. Denis. The statues of the north porch at Chartres.

So far the subject of our study has been man in the abstract—man with his virtues and his vices, with the arts and sciences invented by his genius. We now turn to the study of humanity living and acting. We have reached history.

The cathedral recounts the history of the world after a plan which is in entire agreement with the scheme developed by Vincent of Beauvais. At Chartres, as in the Speculum historíale, the story of humanity is virtually reduced to the history of the elect people of God. The Old and the New Testament and the Acts of the Saints furnish the subject-matter, for they contain all that it is necessary for man to know of those who lived before him. They are the three acts in the story of the world, and there can be but three. The course of the drama was ordained by God Himself. The Old Testament shows humanity awaiting the Law, the New Testament shows the Law incarnate, and the Acts of the Saints shows man’s endeavour to conform to the Law. These three great books, each marking an epoch in history, will form the subject of our study in the several chapters.

I

From the time when it occurred to the mosaicists of Santa Maria Maggiorc to take as their subject-matter a series of historical pictures from the Bible, the Old Testament was a constant source of inspiration to mediæval art, though the great narrative compositions which embrace the whole history of the people of God are not found before the thirteenth century. The windows of the Sainte-Chapelle, for example, offer a complete illustration of the different books of the Bible from Genesis to the Prophets. The light falling through the eleven great windows with their thousand medallions gives a sense of mystery to the history of the heroes of the Ancient Law. These countless compositions, treated after the manner of miniatures, make the Sainte-Chapelle the most wonderful of pictured bibles. In the south porch of Rouen cathedral there is a long series of small bas-reliefs of the same narrative character. Here as in the Sainte-Chapelle the artist has followed step by step the story of the first books of the Old Testament, until at length he was stopped by want of space.

It would be not only a lengthy but a quite useless task to attempt to deal with all the compositions of the thirteenth century, windows and basreliefs, which illustrate different parts of the Bible, and it is sufficient for our purpose to note that certain touching and popular subjects, such as the history of Joseph, recur the most frequently.1 All these compositions devoted to the Old Testament are told in the direct style of a simple story.

Had mediæval artists confined themselves to historical cycles there would be no reason to dwell on them further, but there was in the thirteenth century another and infinitely more curious reading of the Old Testament. The artists preferred for the most part to adhere to the spirit rather than to the letter. To them the Old Testament seemed a vast figure of the New. Following the guidance of the doctors, they chose out a number of Old Testament scenes and placed them in juxtaposition with scenes from the Gospel in order to impress on men a sense of the deep underlying harmony. While the windows in the Sainte-Chapelle tell a simple story, those at Chartres and Bourges show forth a mystery.

Such a method of interpretation was entirely orthodox. But since the Council of Trent the Church has chosen to attach herself to the literal meaning of the Old Testament, leaving the symbolic method in the background. And so it has come about that the exegesis based on symbolism of which the Fathers made constant if not exclusive use, is to-day generally ignored. For this reason it seems useful briefly to set forth a body of doctrine which so often found expression in art.

God who sees all things under the aspect of eternity willed that the Old and New Testaments should form a complete and harmonious whole ; the Old is but an adumbration of the New. To use mediæval language, that which the Gospel shows men in the light of the sun, the Old Testament showed them in the uncertain light of the moon and stars. In the Old Testament truth is veiled, but the death of Christ rent that mystic veil and that is why we are told in the Gospel that the veil of the Temple was rent in twain at the time of the Crucifixion.1 Thus it is only in relation to the New Testament that the Old Testament has significance, and the Synagogue who persists in expounding it for its own merits is blindfold.2

This doctrine, always held by the Church, is taught in the Gospels by the Saviour Himself, “As Moses lifted up the serpent in the wilderness, even so must the son of man be lifted up,”3 and again, “Even as Jonah was three days and three nights in the belly of the whale, so shall the Son of man be three days and three nights in the depths of the earth.”4

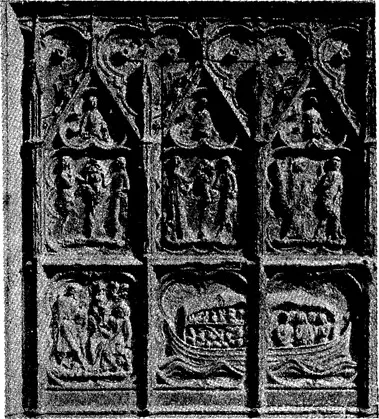

FIG. 77.—EARLY CHAPTERS OF GENESIS (portion of base of doorway at Auxerre)

The apostles taught the early Christians the mystic harmony of the Old and New Law. It is insisted upon more especially in the epistle to the Hebrews. The newly converted Jews, still attached to the letter of the Law, are told how the ceremonies of the Old Covenant were merely figures destined to shadow forth the New,5 and that Melchizedek, king and priest, was an image of the Son of God, who was both pontiff and king. Several passages in the first epistle to the Corinthians and in the epistle to the Galatians, as also several verses in the first epistle of St. Peter, show that the allegorical method of interpretation was known to the apostles.1

But it was in Alexandria in the third century that this manner of biblical interpretation became a definite system. This is not surprising when one remembers that from the first century the Jews of Alexandria, imbued as they were with the Hellenic spirit, saw in their sacred book a symbol only. In order to make his system accord with the Bible, Philo makes the literal meaning of Scripture entirely disappear. In his commentary he interprets Genesis very much as Homer was interpreted by the Stoics, to whom the Iliad and Odyssey were profound allegories clothing the highest philosophy. Thus the Greek genius coalesced with the eastern in that extraordinary city of Alexandria. In some respects Philo may be considered as the first of the Fathers, and it cannot be doubted that both Clement and Origen were his pupils.

It is in Origen that the allegorical interpretation of the Old Testament first appears as a finished system. He begins by laying down as an axiom that the meaning of Scripture is threefold. For Scripture is a composite whole made like man after the image of God. Even as there are in man three components, body, vital principle and soul, so there are in Scripture three meanings, the literal, moral and mystical.2 But, he adds, all passages of Scripture do not lend themselves to a triple interpretation ; to some it is convenient to attach a literal meaning only, to others a moral or mystic sense. Origen challenges the literal sense in particular, for to him the letter seemed to contain absurdities and contradictions which had given rise to every heresy. “Who is stupid enough,” he says, “to believe that God like a gardener made plantations in Eden, and really placed there a tree named the tree of life which could be seen by the bodily eye ? “3 Eden is nothing, he explains, but an allegory of the future church.4 In his commentaries on Scripture the letter entirely disappears. When interpretating the passage in Genesis in which it is said that God made for Adam and Eve tunics of the skins of beasts, he says, “Where is one to find the mean intelligence, the old woman who would believe that God slaughtered animals in order to make clothing after the manner of a currier ? “To avoid such an absurdity it should be understood that the tunics of skins designate the mortality which followed the sin. “It is thus,” he adds, “that one should learn to find hidden treasure beneath the letter.”5

Origen attempted to justify this intrepid method ; the kind of interpretation he adopted had come from the apostles and been orally transmitted down to his time. But it is evident that he allowed himself to be carried away by his vivid imagination. In the flame of a genius which has been compared to a furnace in which even brass liquefies, the literal meaning of Scriptur...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Translator’s Note

- Preface

- Table of Contents

- Alphabetical List of Illustrations

- Introduction

- Book I

- Book II

- Book III

- Book IV

- Appendix

- Bibliography

- Index of Works of Art referred to